Considering the Silence of Teenage Boys in the Wake of My Son’s Traumatic Injury

Susan Conley on Stoicism, Recovery, and Trust

Just before my son Aidan broke his neck on a mountain-bike last June, he had a feeling that things were about to go very badly. He hadn’t seen the jump built into the trail. And because he’s not really a mountain biker, he stayed in his seat and went flying over the handlebars and landed hard on the back of his neck—the soft part right below your skull. Aidan’s best friend Harry told me later that when he saw Aidan fall, he was sure he’d been paralyzed.

At seventeen, and six foot-four, 200 pounds, there was a lot of Aidan to fall. And it was the way he fell, Harry said. Aidan lay by the side of the trail and his neck really hurt, but he stood up, said he was good, and climbed back on the bike. Then he and Harry and their friend, Oliver, started pedaling up a steep hill. Aidan’s left knee was bleeding, and he had pretty bad abrasions on his stomach and shoulder and the bridge of his nose, but he kept riding. I’m not sure he got to the top.

His eyes gave him away—the pupils were darker and shiny and looked like they were trying to convey something urgent to me, they just didn’t know what.At some point he said he wasn’t feeling that great and would head back to the trailhead on his own. A surgeon friend of mine saw his CT scan at the hospital the next day and said she wanted to throw up. What freaked her out most was how long it took us to get Aidan to the ER. Fifteen hours since time of accident. All he would have needed, my friend said, was to trip in our bathroom or bang his head on a door. She didn’t finish the rest of her sentence.

When Aidan got home from the trail, he found me on the couch where I was reading my grad students’ stories, and he told me that he’d fallen off his bike. I hadn’t known he was biking. He almost never biked. His teen wolfpack had just launched their summer landscaping operation, and they liked to kick soccer balls in the off-hours and swim. But Covid had closed the fields, and the wolves had broadened their range. “I fell on my head,” he said. “No big deal. Just some whiplash.” But his eyes gave him away—the pupils were darker and shiny and looked like they were trying to convey something urgent to me, they just didn’t know what.

I nodded. “Probably whiplash.” Then I asked why he was only now telling me that he’d fallen. “You could have called.”

“It’s nothing, Mom. I just went back to the car and waited.”

When I wondered out loud why neither of his friends had biked back to the car with him, he said he’d convinced them he was okay. Fooled them, might be another way of saying it. “They never knew how bad it was, Mom. They never had a clue.”

I have two of the teenage boy species and have been deciphering boy code for twenty years, so I knew how much Aidan hadn’t wanted his friends to know he’d been hurt. Silence in the face of pain is part of the whole boy-honor code, and the rules are pretty clear—mainly that to show emotion is to appear way too vulnerable. I still wanted to press Aidan on why he hadn’t told his friends, because he loved these guys. They were a second family. But he looked really tired now and was holding his head at a weird angle, so I backed off and got him Advil and made him go to bed. Then I picked up the story I’d been reading on the couch by a woman who’d lost her mother to Covid. She hadn’t been able to say goodbye and the shock of it was just starting to set in.

Another woman in the class had lost her father to the virus. The language in both pieces was honest and moving. All of the students in the class were trying to make sense of their lives in the face of Covid, which kept delivering grief to their door in the shape of death and lost jobs and such isolation and loneliness.

The night before, I’d talked to the class on Zoom about the reckoning that needed to happen to write with a kind of almost reckless honestly. How if you wanted to tell something truly new about grief or death or abiding love, you could push beyond confession and ask the hard, crucial questions that helped make the meaning. Sometimes, I said, these questions sit over the story unanswered. The thing is that you’ve asked them. Then sometimes the reader will help answer them.

The morning after his accident, Aidan got out of bed and said the pain was so bad in his neck that he couldn’t move his head. I had to ease him into the car slowly, and while we waited in the ER he couldn’t get relief. He tried leaning against the wall of the lobby but that didn’t work, so he stood by some beige chairs over on the right side of the room and jutted his right hip way, way out, so it looked like he was trying to support his head with his hip. A kind, mop-headed nurse named Sam finally took pity and walked us down a back hall to a square, white room with a glass door. Two doctors came in and asked Aidan to make a fist. Then they ran their fingers across the soles of his feet and the palms of his hands and his thighs and chest.

Could he feel their fingers?

Yes, he could.

“You’re sure you feel that?”

Aidan was sure.

The doctors concurred—most likely bad whiplash. Then they wheeled him away for an MRI and CT scan just to be sure.

I sat in the vinyl chair in the corner while he was gone, crafting an email to my writing workshop. HOW DO YOU REALLY FEEL? I wrote in all caps. Then I bolded it and asked them all to be as completely honest as they could be in their next drafts. WHAT IS IT THAT YOU’RE REALLY ASKING HERE? WHAT IS IT THAT YOU MOST WANT TO KNOW?

Just then two doctors and Sam, the nurse, wheeled Aidan back into the room and announced four fractures of the neck. The doctors said they were part of the Head Trauma Unit as they ran their fingers over the soles of Aidan’s feet and his palms and chest. He could still feel it.

Two different brain surgeons appeared and hovered, then left and came back. No one let him eat anything. Surgery felt imminent. One of the surgeons, a tall, burly man in Army-green scrubs with a rust-colored beard, said that the jelly between two of the discs in Aidan’s spine had squished out during the accident, and this was what they were interested in. Not the bones as much as the jelly.

But none of the doctors could detect neurological damage. The rust-colored beard smiled and said Aidan had come to them as if from outer space, because head-trauma patients don’t walk in the front door of the ER. They come by ambulance. Or helicopter.

Then everyone left for a moment, and Aidan and I were alone. Just the two of us, letting the shock settle. We didn’t speak at first. I put my hand on his arm. I wasn’t afraid to touch him. I was more afraid to lose him to his silence. I so very much hoped that we still had our own flavor of telepathy, he and I. That we still had our language—mother and son. I would not leave him. I didn’t need to ask him how he felt. I could feel his sadness and his fear. They filled up the room.

But what I wanted most was for him to dare throw the stoicism out. The question I was asking, and I knew I was asking it, was whether he could he allow himself to show the fear. But that’s not what I really mean. What I was really asking was did he trust me anymore? And was there still a boy inside that grown-up looking body? My boy. The one I hadn’t seen in a long time.

What I wanted most was for him to dare throw the stoicism out. The question I was asking, and I knew I was asking it, was whether he could he allow himself to show the fear. But what I was really asking was did he trust me anymore?Two tears pooled in the corners of his eyes and made their way down his face, and they gave me such relief. I knew if he allowed himself to feel the pain, then over time he could let it go. More tears came and I held on to his arm, so he understood that I saw him. That was the thing: that I saw him, and he wasn’t a boy, all alone.

Our time in the hospital was in many ways our worst time together, and more reckoning was to come. But it was also the beginning of something new. Because Aidan started talking again in that hospital room. First with the tears and later with words. The talking really hasn’t stopped. In this way it’s been a kind of homecoming—the way he’s let his guard down.

Each morning, for weeks after, my husband and I took Aidan’s night-brace off and strapped him into the day-brace before he could get out of bed. The day brace had two metal rods that started at his waist and connected to a hard collar that pressed into his chin. You could feel the trust between the three of us in that bedroom every morning while we navigated the brace, and each day after we were done, Aidan said thank you.

I think the wolfpack made a secret vow to never let him be alone, so they came to the house in masked-shifts bearing take-out containers of anything from Chipotle. He let them help him with his brace too, and no one downplayed the fear. No one questioned his pain.

About a week later, we watched Ferris Bueller’s Day Off—Aidan and his older brother and my husband and I. Aidan was in the brace on the couch, so he could barely move his head. But he leaned in my direction and whispered that he’d thought about it and had decided to get better as quickly as possible. “I’m only going to be optimistic, Mom. Only going to think good thoughts.”

It was dark in our living room, except for the bluish light from the tv, and I smiled. There you are again, I said to myself. There’s the boy.

__________________________________

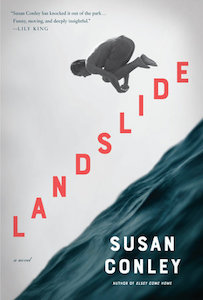

Landslide by Susan Conley is available via Knopf.