Compartmentalizing and Coping: Life as an Emergency Doctor During COVID

Robert Meyer, MD Reflects on the Anxieties of His Occupation in the Last Year

In March 2020, former New York Times journalist Dan Koeppel texted his cousin Robert Meyer, a twenty-year veteran of the emergency room at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx and asked On a scale of 1 to 10, 10 being overwhelmed, where do you think you are? Meyer said: 100.

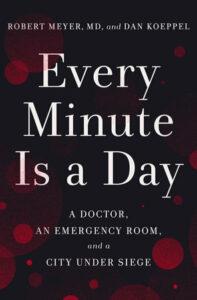

As the pandemic progressed, Meyer continued to update Koeppel with what he’d seen and whom he’d treated. The result, Every Minute Is a Day, is their co-written record of historic turmoil and grief from the perspective of a remarkably resilient ER doctor.

*

A former patient of mine, a psychotherapist, thinks ER doctors live in denial, that it would be impossible to see what we see and not have it take a toll. I don’t agree. I think we are, in fact, a well-adjusted group, even with all the risks and drawbacks. We got into emergency medicine knowing it’s a profession that’s often sad and sometimes tragic, but we each develop our own coping mechanisms. Sometimes that means a lot of compartmentalizing.

Now there’s another layer of fear, another threat facing ER doctors, who are always balancing denial and self-confidence—or even hubris—in order to shield ourselves from the risks we’re taking. We’re beginning to understand that Covid has neurological effects; it can influence your mood or your ability to think, causing encephalopathy (brain inflammation) or brain cell death via oxygen starvation, both of which can lead to cognitive impairment in the form of psychosis or delirium.

We hear that someone has died and immediately we run down the list of comorbidities associated with the disease. We selfishly hope to hear that they were sick to begin with.

It seems almost inevitable that we’re all going to get Covid. So we’ve begun to play a strange game: We hear that someone has died—it could be a doctor—and immediately we run down the list of comorbidities associated with the disease. Did the person have asthma? Were they overweight? We selfishly hope to hear that they were sick to begin with. And most of them were, but there are outliers, perfectly healthy folks who end up in the ICU.

More and more doctors are getting sick, like James T. Goodrich, who ran our pediatric neurosurgery department for more than 30 years. With his distinctive white hair and beard, you couldn’t miss him walking the halls. Everybody knows him because he got Montefiore big headlines when he successfully separated craniopagus (fused at the top of the skull) conjoined twins, first in 2004 and again in 2016. It’s a really tough operation, needless to say. In 2004, a round of tests before surgery showed that the amount of brain tissue the babies shared was more than expected. Some advised against the operation. But he went ahead, and sixteen years later, that first set of twins are alive and well. They’re going to be 20 next year, the same age as my son.

Nobody knows how Goodrich got sick. He was healthy and strong and took every precaution. He worked through early March, then fell ill and died, on March 30. His one comorbidity was his age: He was 74. He worked just a few stories up from the ER. When I hear he is dead, I think, How is that even possible?

*

Deb White is the medical director of the emergency department here on the Weiler Campus. It takes a special person to do what she does. I was offered the equivalent job on Montefiore’s Moses Campus in 2005 and made the mistake of saying yes. I lasted all of two days attending meetings, doing policy planning, and playing nicey-nice. We still joke about it.

Deb is a star, and she is great at all the stuff I suck at. Deb and I went through our medical residency together in the early 1990s, and because of that we have a special relationship. She was born and raised in the Bronx and has chosen to stay here, although she’s brilliant enough to work anywhere she might want to. For years, she was one of the few Black women working as an ER doctor anywhere in the United States. Deb is a great boss: She always has my back, and I always try to have hers.

Deb is a classic Montefiore ER doc: deeply committed to the proper treatment of the hospital’s neediest patients. She protects the doctors who work for her, but she puts patient needs first and doesn’t mind challenging leadership when she believes hospital protocol is getting in the way of patient care. That’s why John Gallagher chose her as director in 2013. Gallagher trained Deb when she was a resident at Jacobi Medical Center, a city hospital right across the street from Montefiore’s Einstein Campus. She’s told me that she enjoyed her residency in large part because of Gallagher’s style. His approach was always personal, treating the patient, not just the medical condition or the disease. She credits Gallagher’s mentorship with changing her not just as a doctor but as a person. I know exactly what she means when she says that she’s worked every day of the past seven years to make good on the potential for leadership Gallagher saw in her. I feel the same way.

Deb also recognizes—and I’m pretty sure she’s right—that few others in the hospital’s leadership would have identified a Black woman to lead the emergency department on the Weiler Campus. An astute judge of talent, Gallagher chose her for the qualities she shows every day: She loves what she does, she’s great at it, and she works tirelessly for the people of the Bronx.

In the first few weeks of this month, she’s been through hell trying to make an overwhelmed emergency room function; managing shifts and sick doctors and staff; rationing equipment and protective gear; and helping dozens of patients, many of whom won’t survive. She’s in the ER practically 24/7, whether to take a meeting or head up the Covid Zone. She never stops moving.

In a meeting, Deb brings up something we haven’t talked about: depression, stress, and suicidal ideation during times of crisis.

Deb also never stops thinking. In addition to her medical degree, she has an MBA from George Washington University. In my career, I’ve never seen anyone more willing to try things, to entertain new ideas, in the spirit of improving patient care. One example is wait times. Most people dread visiting an emergency room not just because they might be really sick, but also because they might not be seen for hours. When I was a resident at Jacobi, there used to be a clock that indicated how long the queue to be seen was, and sometimes it showed a wait time as long as ten hours. Emergency room queues have become such a huge issue that facilities are now rated on how quickly they triage, admit, and discharge patients. Billboards along local highways even advertise, in real time, how long somebody is going to have to wait to be seen at a nearby ER.

One thing Deb did right away was simply to eliminate our waiting rooms. Nobody who comes in has to sit and wait to be evaluated. It doesn’t matter whether you arrive on foot, in a car, or by ambulance. I’m not saying that there aren’t bottlenecks, but most of the time, within minutes, you at least get to talk to a medical professional—a doctor, a physician’s assistant, or a nurse—about what has brought you in. I think that’s a huge boost for the patients, and I hope that it improves how we’re seen not just by our patients but by the entire Bronx community.

But right now, in the spring of 2020, these improvements in patient care and perception can’t help the fact that we don’t have nearly enough Covid tests for either staff members or patients. That has led some of us to pursue creative acquisition methods. I managed to score 25 antibody test kits through a friend of my daughter’s. But then I was left with the awful task of figuring out who would get tested and who wouldn’t. I tested myself, but I skipped my family and brought the kits to work, testing whomever I could. Colleagues who didn’t get a test were upset with me for rationing, but what else could I do? There just weren’t enough kits.

But here’s what’s really unnerving: Everyone who took one of the antibody tests turned out to be negative. Given our level of exposure, you’d think we’d be relieved. Instead, we’re disappointed. How can it be that in spite of our obviously intense exposure to this virus, we don’t have antibodies? No antibodies means any or all of us could get sick. On the positive side, maybe this means that we’re doing a good job with our PPE and the hospital protocols.

*

I’m trying to keep a semblance of regular hours, to space out my shifts and work every three or four days rather than back-to-back. In a meeting, Deb brings up something we haven’t talked about: depression, stress, and suicidal ideation during times of crisis. She says that she’s getting more worried about the doctors on our team: whether we’re going to start getting sick, whether we’re going to start manifesting our own mental health issues, whether the coping mechanisms we’ve all relied on are going to be up to the task. Friday night really got to her. People were dying all around, and a 40-year-old man sobbed in her arms, begging her not to let him die. He said he had a young kid. She comforted him, but it came at a cost, and she recognizes that some of us might be going through similar experiences.

“So I’m just checking in,” Deb says, “wanting to make sure you have a chance to talk about your feelings.” She pauses before continuing. “I want to encourage each of you to take advantage of the professional health services provided by Montefiore.” Her offer is met with a palpable silence. No one is ready to talk about their anxiety, at least not in such a public venue. No one wants to appear weak or to disturb the balance that we all must negotiate internally in order to be fully present, to do the job we were trained to do.

My dad has a saying, “Grief is indivisible,” meaning that even if you could share the feeling, it wouldn’t reduce what you feel. Right now, it seems like the same thing is happening with our collective anxiety. All of us are resigned to probably getting sick at some point, and we are all dealing with death every day. We’re all trying to find ways to handle both. Deb called the meeting so that we could talk things through, but no one has anything to say.

_________________________________

This excerpt is adapted from Every Minute is a Day: A Doctor, An Emergency Room, and a City Under Siege by Robert Meyer (an emergency room doctor at Montefiore Medical Center) and Dan Koeppel (Robert’s cousin and an award-winning writer). © 2021 by Robert Meyer and Dan Koeppel. Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Robert Meyer, MD, and Dan Koeppel

Robert Meyer, MD has been an emergency room doctor for over twenty-five years, spending most of his career at the Bronx’s Montefiore Medical Center, whose emergency rooms are New York City’s most visited, and among the nation’s five busiest. He is as well an associate professor of emergency medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Meyer grew up in Queens, New York, and now lives in Hartsdale, New York, with his wife, Janet. He has two grown children, one in college and one in medical school.

Dan Koeppel is a former executive editor at The New York Times’s Wirecutter. He has written for national publications including Wired, Outside, National Geographic, and The Atlantic and has won a James Beard Award for his food writing. Koeppel is also a recipient of a National Geographic Expeditions Grant. His screenwriting credits include Star Trek: The Next Generation, and he is the author of Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World. His writing has been anthologized three times in the Best American series. He grew up in Queens, New York, and now lives in Portland, Maine, with his wife, the writer Kalee Thompson, and his two young boys.