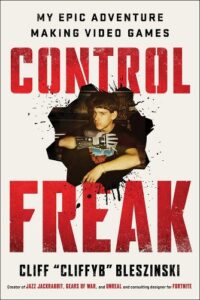

Cliff Bleszinski on Finding Lifelong Happiness and Eventual Success in Video Games

“Being a gamer was me, who I was. I couldn’t change that. Why would I even want to?”

“Clifford, come on over,” said Rick Adams. “I want to show you something.”

Rick, who was four years old than me, lived across the street. He was one of the accomplices in the ninja escapades. He and his sister were big stoners. For some reason, he felt it was his obligation to introduce me to knowledge and activities close to his heart. He taught me about groupies, showed me my first porn movie (a late-eighties video called Pumping Flesh), and let me play The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy on his Commodore 64.

He knew all this was true what-the-fuckery to me, and so when he told me to come over to his house, I made a beeline to his front door. He told me to follow him upstairs. We took the stairs in giant leaps and darted into his bedroom. He grabbed a booklet and thrust it toward me.

“Look at this,” he said.

It was the instruction manual to The Legend of Zelda.

“My friend has the game,” he said. “He told me that you can burn down a tree or bomb a rock and find a secret underground location.”

“It’s the hidden block in Mario taken to the next level!” I said, leafing through the instructions.

“And the cartridge is gold,” he said. “Real, actual gold.”

At thirteen years old, that became my life’s mission: to get the highest score possible in Super Mario Bros.In reality, it was painted plastic, but like so many other kids, I bought into the fable. I put the instruction book down on Rick’s desk and slowly raised my eyes until he could see my thoughts. Holy shit. Zelda was special. I had to have that game. That summer, after saving every dime I made from my paper route and a part-time job at a local golf course, I persuaded my mother to drive me to Toys “R” Us and I bought it. Back home, I unpacked the game, slipped in the cartridge, and played for the next twenty-four hours. Until I was able to put a notch on the back of my NES. Then I informed Rick.

“I beat it,” I said.

“Dude, you just got it,” he said.

“I know.”

“Fuck.”

“Yeah, and guess what?”

“What?”

“There’s a second quest that opens up.”

“No way.”

“Seriously, you just keep playing it.”

It was a prelude to more and bigger conquests. Starting mid-1987, I subscribed to the Nintendo Fun Club News, the quarterly promotional magazine started by former warehouse manager–turned–NES guru Howard Phillips. This was pre-internet, so news about games came from friends, coming-soon info on game boxes, TV commercials, and now this incredible new magazine, whose every word and picture I devoured.

Each issue in the Nintendo Fun Club News contained a message from Howard, articles about new games, tips and tricks, game reviews, jokes, and, later, a comic strip called Howard & Nester. It portrayed Howard in his signature bow tie as the gaming wise man and Nester as the snotty Nintendo know-it-all who was like all of us reading the magazine. In the second issue, delivered to my house in 1988, I noticed a feature that had escaped my attention previously—the high score section—and something clicked in my brain. I wanted to see my name on that list. Not just on the list. On top of the list.

At thirteen years old, that became my life’s mission: to get the highest score possible in Super Mario Bros.—9,990,950.

The game only went up to that number before resetting to zero. Only a few others had achieved that score. Their names were in the magazine. I wanted to see mine there too. I read the rules: all I had to do was take a Polaroid picture of my high score and mail it to Nintendo. If approved, they would put my name in the magazine and…I would be famous.

Determined and disciplined, I played every day for hours. I developed my own strategy. I ignored the Warp Zones and took my time. Shortcuts were no good if the objective was getting a high score. In Super Mario, you had to milk every single level, take out every enemy, and get every coin. As I got close to the end, I jumped on the lumbering turtles and pushed their shells away, causing them to ricochet off the odd, medieval world’s blocks. If I caught one on a staircase, I could keep a tight cycle of shells ricocheting as my score zoomed up.

Millions of people were seeing my name, including the Nintendo master himself, Howard Phillips. I was famous.As I navigated my way through the challenges in each level, the outside world disappeared, and I literally entered the game. I saw pathways, shortcuts, and opportunities. I thought like the people who had made the game, and I just knew how to win. It was that way with every game. But Mario was special.

Then came the day when I hit the high number: 9,990,950. I stared at the screen, nodded at the score, and thought, Mission accomplished. I grabbed my father’s Polaroid camera and, sixty seconds later, I had the evidence in hand. I showed the photo to my family and several friends before mailing it to Nintendo. Then I waited. I thought I’d receive a handwritten note from Howard Phillips within a couple weeks saying, “Nice job, Clifford.” But I didn’t get a response. Nothing. Crickets.

A month later, the next Fun Club News magazine showed up in our mailbox. Though I still hadn’t heard anything from the publication, I remained hopeful. I ran inside, slid into a chair at the kitchen table, and flipped through the pages until I came to the section. And there it was—my name, Clifford Bleszinski—at the top of the High Score list. “Yes!” I exclaimed, before showing my mother (“Look, Mom, I did it”) and my brother (“Check it out”) and later, my father (“Isn’t it cool? What do you think?”).

My name also appeared in the next two Fun Club News issues and the legendary next iteration of that magazine, Nintendo Power. I guessed the list didn’t change that often. Evidence of just how difficult it was to make it in the first place. But there I was in black and white: Clifford Bleszinski. Clifford Bleszinski. Millions of people were seeing my name, including the Nintendo master himself, Howard Phillips. I was famous.

“Fuck yeah!”

*

At school, I was nicknamed “Nintendo Boy.” I didn’t especially like it, but the nickname was one of those things where if the shoe fits… I was a fixture in the computer lab, where I played Oregon Trail to death. Literally. I kept dying of dysentery. I spent so much time there, they should have called it the Cliff Bleszinski Computer Lab. One day it seemed they did. I got there and saw, taped to the door, the now famously ironic Far Side comic of parents watching their son playing video games as they imagined a future newspaper’s Help Wanted section with six-figure job openings for a Nintendo expert and Super Mario Bros. player. My name was written in large block letters at the bottom.

I tore it off the door and threw it away. That wouldn’t be my reaction now. Today we know the world has not only embraced but come to be defined and ruled by technology and the nerds who understand it. Video game creators, streamers, YouTubers, and cosplayers are the new celebrities. But back then, and especially in middle school, it wasn’t easy being a gaming nerd. I couldn’t change my skinny physique. I have no idea why I thought my fanny pack was essential (and cool), but I did (it wasn’t). And being a gamer was me, who I was. I couldn’t change that. Why would I even want to?

Today we know the world has not only embraced but come to be defined and ruled by technology and the nerds who understand it.One reason might have been it made me easy prey to those who needed to prove they were better, stronger, and cooler—perhaps because ultimately, they were even more insecure and uncertain about who they were than me. The proving ground was the bus ride home in the afternoon. The twenty-minute trip was often a Lord of the Flies–like voyage of bullying and survival. I was routinely pushed, shoved, and teased. Once I had gum put in my hair. Another time a kid shook up a Coke behind my back and dumped it on my head while a chorus of his lame friends laughed.

That was the worst. Humiliated, I stormed up to the front of the bus and insisted the driver stop even though we were still a half mile from my house. He tried to ignore me, but I shrieked “Stop!” and he knew he had to pull over and let me out or something terrible was going to happen that he wasn’t equipped to handle. As I bolted off the bus, someone behind me whined, “He’s going home to play Nintendo.”

I ran through the woods, hurrying past the pond where I played hockey and the junk pile where I hunted for snakes, until I was by myself in the middle of nowhere. There I finally stopped, caught my breath, and turned back toward where the bus had let me off. “Fuck you,” I screamed at all of them. “Just fuck you!”

No one was home when I got back to my house on Russet Lane. That was fine with me. I relished the freedom and the lack of having to explain what had happened on the bus, why my eyes were red and I was out of breath. I took off my Coke-drenched clothes, put them in the washing machine, and showered, scrubbing furiously, as if trying to shed a layer of skin from my awful day at school.

Still, I think kids growing up in today’s hyper-connected world have it tougher than I did. At least the bullying didn’t follow me onto Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok. And in some way, those assholes on the bus motivated me. As Frank Sinatra once said, “There’s no better revenge than massive success.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from Control Freak: My Epic Adventure Making Video Games by Cliff Bleszinski. Copyright © 2022. Available from Simon & Schuster.