That night, when everyone was asleep, Charlotte could bear it no longer. She slipped from beneath her thin blanket and sat up for a moment to orient herself in the gloom. She patted her pocket where she kept her black book and its weight against her hip reassured her. The fire over which they had cooked soup was now merely smouldering embers. Around her the dim shapes of travellers huddled under their blankets. Marguerite and Madame Leroux were in the cart with the baby, while the men slept on the ground wrapped in blankets. The donkey stood beside the wagon with its head bowed, dozing. Overhead, through the leaves, the night sky was black, dotted here and there with pinpricks of light. Stars. The moon was low, a few days past full. No one moved. A fox cried out, an animal crept through the undergrowth. The forest went about its business.

Charlotte picked her way over to where Lesage was asleep under his own bedding. She shook him until he woke, startled and wild-eyed, flailing clumsily at her.

“What? What’s happening? What is it, woman?”

“Is it true what you told Monsieur Boucher?”

He looked around blearily. “What did I tell him?”

“That my son is probably dead? That there are sorcerers in Paris who might use him for their own purposes? Murder him? Tell me. What do they do with them?”

Lesage wiped a hand across his greasy face. His breath stank of wine. “How do you know what I told him?”

Charlotte shook him again. “Tell me,” she hissed.

“I only told him that to frighten them. A story, that’s all. I told him that to give our situation more urgency, you see. So these damned troubadours would move faster. No, no, no, Madame Picot. You misunderstand. They won’t hurt him. They might . . . might make the children work as servants or maids, that’s all. They hire them out as mourners at funerals and the like. Nothing more than that. I’m sure no harm will come to your boy. We’ll find him soon enough.”

“Are you telling me the truth?”

“Of course.”

She hesitated. “I want you to read my cards for me.”

“Now, madame? But it’s so late . . . ”

She pulled his blanket off him. “Yes. Immediately.”

Finally, cursing to himself, Lesage got to his feet, scrabbled through his satchel and produced his deck of tarot cards. Squatting on the ground with his blanket draped like a cloak across his shoulders, he unwrapped the cards from their filthy scarf and held them out to her. They shone dully in the moonlight. Charlotte was fearful. She shivered in her shawl.

“Now,” Lesage said, “close your eyes and place your hand on the deck for a moment. There. Like that. Thank you.”

When, at his instruction, she opened her eyes again, he arranged five cards in the shape of a cross, mumbling several incantations or curses under his breath as he did so. He had removed his hat to sleep and Charlotte could see where his hair had grown on his scalp, but patchily, like a blighted crop. His own hands were rough. His fingers were calloused and the backs of his hands were as scarred and leathered as those of a field worker. With each card he laid down, he muttered with surprise and rumination. Charlotte drew breath, as if scorched. Indeed, the cards were as beautiful and terrifying as fire.

“Very interesting,” he said at last, and tapped the cards one by one, as if she were unable to read their names for herself. “Here is the Empress, the Magician, the Queen of Coins, the Hanged Man and, there, this last one is Judgement.”

“Do they say if my son is still alive?”

“Not exactly. Alone, the cards have varied and inconclusive meanings, but together we might draw forth some predictions about your future.” Here Lesage made a scooping gesture with his hands, as if gathering these disparate meanings together. “I think you have had a troubled life, madame, but perhaps no more so than any woman. I can tell you are a very caring woman. Most fertile, which is important, of course, and you have been a valuable wife. You are also devout, madame. That’s excellent, and so important in these godless times. You should live to a good age, I think. No madness that I can see. A content enough childhood, I think?”

She shrugged and tucked a strand of hair behind her ear. Her own contentment was not something she’d had occasion to consider. But yes, she supposed so. More content than some, less so than others. She was moved to think it might be so visible on these cards. “But what of Nicolas?”

“Patience, madame. Let me see. I can also see death and sorrow. Children lost . . . to plague, I think?”

“Yes. Two of them to scarlet fever. Another of something else. We never knew what. He lasted only one year. Less.”

“A terrible thing.”

“With each card he laid down, he muttered with surprise and rumination. Charlotte drew breath, as if scorched. Indeed, the cards were as beautiful and terrifying as fire.”She nodded but was unable to speak. Yes, a terrible thing. A most terrible thing. The candles, their skin slackening as it fell away from the bones that supported it, the suffocating sense of inevitability when they first fell ill. Oh, oh, oh. This is how it is, how it had been, how it will always be. Prayers and a coin in their hands before they were rolled gently into their graves. A grave. No more than a hole with a dignified name. She wondered often about her son and her daughters all these years later and was glad, at least, they each had the company of their siblings.

“This card. The Empress is there in your past. She is a messenger from God, with her wings. Do you see the distaff in her left hand? This is usually women’s business. And the shield with the eagle as its crest? This card is a woman because she is the only means by which one might be brought across from one world to another . . . ”

Madame Rolland, the Empress. Her crown and robes, her face looking off to one side.

Lesage talked on. “How one might be born, as it were. She is the giver of life. She might summon an angel, for example—”

“Or a demon?”

Lesage laughed. “Or a demon, yes. The Empress offers great power and knowledge. And here”—he tapped the second card he had laid out—“is the Magician. In a physical sense it refers to the liver, trouble with bodily fluids and various humours. Do you have trouble with these things? No. It might also mean an element of trickery or sleight of hand. Someone to be wary of . . . ”

Like you, she thought.

“ . . . but in this position in the spread it might also mean things moving out of sight, hidden from plain view, like the great creatures of the sea. That vast region of things we don’t understand. Have you ever attended the theatre, madame? No? Of course not. Well, sometimes they move items behind the curtain. There are unseen elements that play a role at a later moment in the show; things to appear on the stage much later in the performance, if you understand what I mean?”

Charlotte was unsure if she did understand. She leaned over to look at the card, which bore the illustration of a man in a wide-brimmed hat standing behind a table with coins and cups upon it—the sort of fellow one saw gulling people out of their money at markets and fairs. “And what is this third card? The woman holding the round object in her hand?”

“This card represents the near future. That is the Queen of Coins, madame. The round shape in her hand is a coin. A coin. This is interesting. You know, this is one card I have rarely put out for anyone in all my years of doing this.” Lesage licked his lips. He seemed greatly excited to see this particular card. “This indicates . . . great prosperity, madame. Money in your future. How far distant I could not say. But perhaps not very far.”

Lesage paused and nodded, as if in dialogue with himself. He grunted ruminatively. “And this card here is the Hanged Man.”

The card bore a colourful illustration of a man hanging upside down in a sling with his legs crossed at the knee. His breeches were blue, his shoes red and his hair a flaming yellow.

She drew breath, for surely such a card was a bad omen, but Lesage sought to reassure her.

“It’s true that this card appears rather forbidding, but it is, in fact, very good,” he said. “It signifies change, that’s all. Not necessarily death or anything of the sort. No. The Hanged Man. It’s the twelfth card, as you can see. For the twelfth apostle. Some think it represents Judas, but remember the cards do not have definitive meanings. And remember, it was Judas who set the events in motion that led to our salvation. Think about that. Maybe he was actually the most loyal of all the disciples? See his face? Quite calm. Personally, I think the fact the fellow’s legs are crossed in that way is most important. It’s a crossing of sorts to another side. Perhaps the transformation is of a more personal nature. You might get leave to remarry, for instance. Or it’s time to return to your village, perhaps. After all, you are not so old . . . ”

Charlotte stared at the card. The man’s face did not look so calm to her. She shook her head, weary of Lesage’s tiresome riddles. “Say it plainly, monsieur. Please.”

He ignored her. “But here. Do you see this card here? This represents your future. This last card is Judgement. And it’s an interesting place for this to fall, madame.”

She inspected the card. It showed God, or one of his angels, reaching out from red and yellow clouds with his trumpet. A naked, prayerful man and woman were standing below with their eyes cast to the heavens above. The illustration was compelling and Charlotte had to stop herself from reaching out to touch the card, as if by clasping it to her breast she might be relieved, magically, of the pain that had settled there. Oh, my son, she thought. My son, my son, my son. Tears welled in her eyes. Was it better to think of Nicolas constantly, or not at all? For years she had brooded on her dead daughters and her other son, fretted over where they might be, but had her thoughts assisted them or did they merely pain them—and her—even more? Could they hear her weeping all through the night? What could it be like to listen to the longings of those who have loved you, and whom you have loved, drifting across from another realm, one impossible to visit, one barely possible to even imagine? The curé had told her—as he told all the women who lost family to plague or accident—that her children would always be in her heart (“There,” he would say, pressing a finger to his own breastbone so hard that his fingertip would redden), but this was not enough for Charlotte. She wanted her children in her arms, although she never said this aloud for fear of appearing ungrateful, or deficient in her faith.

“Please, monsieur,” she said. “Will I see my son again? Does it tell you that? Please.”

“I’m sure your son is still alive, madame.”

“But do you see it in the cards?”

Lesage glanced at her—a little pityingly, perhaps—before looking down once more at his tarot cards. Finally, he tapped the last card, Judgement. “Yes. This one here is all about resurrection.

Life eternal. God sacrificing his child to save us. You can see the Lord blowing his great horn and the dead rising from their graves to be borne aloft to heaven. All will be well, madame. This is what the card says to me. Do not worry.” He patted her arm.

Charlotte wiped tears from her eyes. She felt overwhelmed and it was all she could do not to clasp Lesage’s hand in her own to communicate her appreciation to him. “And peace? Will we find some peace?”

Lesage seemed perplexed by the question and gazed around at the dark forest beyond the clearing, as if the answer might be found among the trunks and vines growing there in such riotous profusion. He hesitated, and when at last he spoke his voice was thin and dry. “I think few people have complete peace in this life, madame.”

“What does that mean?”

“What could it be like to listen to the longings of those who have loved you, and whom you have loved, drifting across from another realm, one impossible to visit, one barely possible to even imagine?”He regarded her as if he considered the answer to her question obvious. “It means that there is always a cost, madame.”

The following day the countryside became flatter and greener. There were many more people on the roads, and in the fields loomed giant haystacks and windmills larger than any Charlotte had seen before. There were boats on canals and flocks of birds drifting like dirty thumbprints across the cloudless sky. Villages, taverns, carts, cottages, herds of cattle, great houses shining in the distance. Women humpbacked in the fields stood upright—one hand cupped across a sweaty brow—to watch them pass. Groups of labourers squatted beside the road playing piquet on upturned barrels, a procession of monks. There were elegant ladies in carriages, travellers, merchants, beggars, lepers hovering in the shade with their clappers and bowls for coins. And corpses, sometimes, of children and old women and men, at first glimpse a skinny grey foot poking from a bundle of rags, then something bodyshaped, purple-lipped, reeking.

Then, late in the day, Paris appeared. At first merely a grey smudge on the otherwise green horizon, but gradually the city resolved into buildings and spires, drifts of brown smoke and the glint of glass in the afternoon light. Black spots drifted in the grey sky over the city. Crows, Charlotte realised as they drew closer, and she slipped a hand into her dress pocket to touch her book.

She soon heard the human throb of the city, smelled mud drying in the streets after a summer storm. The road became more congested. There were plenty of other carts, people on foot, shepherd boys beating their flocks to market, nobles and priests and pilgrims and thieves. They joined the procession—the saved and the damned—and passed through its gates.

__________________________________

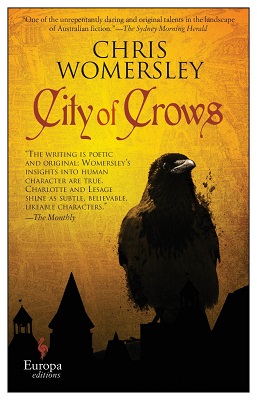

From City of Crows. Used with permission of Europa Editions. Copyright © 2018 by Chris Womersley.