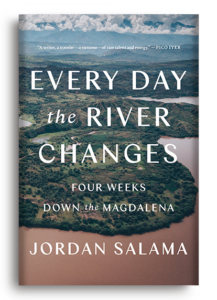

Chasing Legends Down Colombia's Mythic River Magdalena

Jordan Salama Finds Folklore and More in the Laguna de Doña Juana

Juana wasn’t meant to run away from home. At least, that’s how the legend goes.

She was from a wealthy Indigenous family that is thought to have lived, thousands of years ago, in what is today the southwest corner of Colombia. Her parents were endowed with an immense quantity of gold—that mythical gold of El Dorado that, thousands of years later, the Spanish never found. (The Indigenous people knew where the gold was all along, according to their descendants. Just look at their tombs, which were adorned with the stuff. The Spanish simply didn’t know where to look.) Not everyone had gold, though—not even close—and because they possessed such a tremendous quantity of gems and jewels, Juana’s family enjoyed a lifestyle that was lavish compared to that of the rest of their village.

But Juana was a rebellious child, spoiled by the wealth of her family. As she grew older, she fell in love with a man whom her parents did not accept. And then, one day, after her parents gave her a particularly harsh scolding, Juana decided to run away for good and take her family’s riches along with her.

For days she followed river gorges and slick, muddy trails deep into the highlands. Through the thick air and torrential rains, she trudged on, eventually reaching such an altitude where the dense rain forests gave way to the rolling landscape of the Andean páramo, with its volcanoes, low-lying shrubs, and frigid lagoons.

Lagoons are where the major rivers of Colombia are sourced, and none is more revered than that of the Magdalena.

To this day, these lagoons are where the major rivers of Colombia are sourced, and none is more revered than that of the Magdalena, considered for as long as anyone can remember to be the most important river of them all. At its surface the lagoon seems placid, set in a depression among thick grasses and surrounded by a number of small hills, yet it is rumored to be many miles deep. It was in the Laguna del Magdalena where Juana is said to have met her untimely end.

How exactly she disappeared is an often-debated topic of conversation among farmers living in the gateway villages to the páramo. I have heard people, most often the elderly, fervently discussing the tale of Doña Juana—the woman who ran off with her family’s gold—among the colorful open-air produce markets of the Colombian highlands, where unrefined panela cane sugar is sold in the form of bricks and live chickens are pulled from mesh bags and wire cages.

Everyone seemed to have their own version of the story—and in between customers, everyone seemed to have time to tell it. Sitting on a chair beside her bags of grain piled up on the floor, an older saleswoman wearing a red sweater and dark-blue checkered apron told me that Doña Juana was cursed by her parents and was swallowed by the lagoon in its earliest act of magic. Every now and then, a nearby panela salesman would chime in, purporting that, in fact, it was said that along the banks of the lagoon she encountered bandits who roamed the farthest reaches of the mountains. They tried to rob Doña Juana of her gold, and instead of allowing them to do so, she threw herself and her jewels into the headwaters of the Magdalena.

But in every version of the story, Doña Juana drowned—consumed by the lagoon along with her treasure—and from that moment on, the Laguna became enchanted and forever hostile to visitors.

“Our elders always said to approach the Laguna with respect, to go quietly and to not cause too much commotion,” a young man named Arturo told me. He claimed to have been to the Magdalena’s source two or three times in his life. “They told us, ‘If you want to go to the Laguna, you mustn’t make too much noise, because the Laguna is a difficult place, and in an instant, it can cause all sorts of trouble.’ Once, a group of six of us tried to prove that this was a lie—we started yelling and laughing, and suddenly we couldn’t escape its grasp. We couldn’t escape because waterspouts started pouring down from the sky, right into the center of the Laguna, and wintry clouds came in from all sides and trapped us. We struggled to get back to the trail.”

Almost 60 years ago, a woman named María worked with her sister to cook food for men maintaining the trail to the Laguna, and now she recalled the many times she laid eyes on it: “You could’ve been passing through on the sunniest, warmest of days, but when you least expected it, the wind picked up and a storm came in.” Another woman declared that the only way to calm the Laguna’s fury was to throw a live rooster or guinea pig into its waters.

Doña Juana drowned and from that moment on, the Laguna became enchanted and forever hostile to visitors.

I was told that to this day the site remains “sensitive” and must be approached with great caution—if there is too much noise, a violent wind picks up, and the Laguna de Doña Juana, as it is also known, shrouds itself in thick clouds, as if it were angry. Visibility decreases to the point of disorientation, and the soft ground around the edges is prone to sinking. Several people have drowned in recent years, a reminder of what happens when you get too close.

*

The Laguna became enchanted and forever hostile to visitors. For centuries, people have been talking about the Magdalena—not just the Laguna, but the entire river—as “enchanted.” A vital source of water and life for so many generations of communities comprising a vast majority of Colombia’s population, the Magdalena often flows right through people’s towns. It enters their homes as fish on the table, their schools as the history of their country, their streets as maritime cargo and passengers that fill their trucks and carts. The river passes by men resting on its banks, in the shade of guadua trees, taking a brief respite from the oppressive heat of the lowlands before returning to work in its waters; by women washing clothes in the muddy shallows; by the millions of cows grazing in flooded pastures. It makes sense, then, that such a vast discharge of life has often been understood through legends and folktales.

These stories began with Indigenous peoples, who built enormous stone statues that interpreted the lives of the lizards and the monkeys and revered the natural gods that gave all of them life. When the Spanish conquistadors made inroads into the continent in the 16th and 17th centuries, often literally carried on the backs of the subjugated natives who already knew the terrain so well, they were so astounded by the immense biodiversity of the tropical Americas that they believed it to be the site of the Garden of Eden and the creation of the world—and the Magdalena, once a jungle river rushing through deep green landscapes yet untouched by the destructive hand of humans, was believed to have been one of the four rivers of paradise from the book of Genesis. Though scientists like Alexander von Humboldt—the Prussian botanist who led several famed expeditions into Colombia at the beginning of the 19th century—later dispelled these notions, by no means did spiritual and religious associations with the river ever entirely disappear, even as its pristine natural backdrop did.

Most common today are the oral histories, myths, and legends— like those of the Laguna—that run the length of the river basin and vary from town to town. They remain in the local lore and serve as warnings or teachings about the river for those whose lives depend on it—the Laguna de Doña Juana, for example, served for years as a cautionary tale for the many traders who passed it by while crossing the mountains. Other stories of the Magdalena have reached far beyond the places where they began: “I know every village and every tree on that river,” claimed Gabriel García Márquez, Colombia’s most famous and beloved writer, in a 1989 interview with the newsmagazine Semana. In his books, which have been translated into hundreds of languages and read all around the world, García Márquez so vividly portrays the intersection of the magic and the real along the Magdalena’s banks that some villagers told me they believed his novels to reflect the true stories of their lives.

There are the remaining megalithic statues, animal-like figures carved into four-meter slabs of volcanic rock, which still preside over the gorges and rolling hills of the upper reaches of the river, studied by archaeologists attempting to solve the mysteries of a civilization that thrived and then disappeared without a trace. Children who have nothing to play with but scraps of river flotsam, which they manage to fashion into shimmering toys to pass the time. Change makers, regular villagers and townspeople, helping in the most unconventional of ways to pull their communities out of the violence that destroyed livelihoods for so many years. Artisans and engineers who have dedicated themselves to their trades with such steadfast devotion that for them, despite the turbulence of the world swirling all around, time seems to stand still. Each of these encounters takes place in such a vastly different setting that it could at times feel like an entirely different country altogether, if it weren’t for the unmistakable Magdalena threaded throughout the varying landscapes, carrying sediments from places past.

*

The legend of Doña Juana and the enchanted laguna is almost prophetic, reflecting the last 100 years of the history of not only the Magdalena River but all of Colombia. Years ago, during the “golden age” of the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s, triple-decker steamboats so stunning they could have been a thing of fairy tales shuttled passengers and cargo along the Río Grande de la Magdalena from inland cities to the coast and beyond. Equally luxurious railroads followed the course of the river of gold, which flowed through thick rain forest and harbored vast quantities of fish and wildlife. Common sights and sounds included howler monkeys screeching in the trees and caimans sunning their leathery backs on the shores. The Magdalena River was the crown jewel of Colombia.

Toward the latter half of the 20th century, though, the situation worsened. Prospectors of all kinds stripped the forest of its trees and shot the caimans for sport. Unrestrained by the roots of the jungle, land spilled into the river and built up upon itself, creating embankments of sediment that blocked the passage of the steamboats in many critical places. What remained of the navigable river was shrouded in decades of war, under constant threat from armed groups vying for control of the land, and the Magdalena quickly became an epicenter of the Colombian armed conflict, which began in 1964 and has left more than 260,000 people dead and several million displaced over the course of nearly 60 years. There were days when fishermen would see more corpses than boats floating down the river and when townspeople would witness assassinations from their doorsteps.

The ever-shifting fortunes of the Colombian people have long mirrored the rise and fall of their country’s greatest river. Perhaps this can be attributed to the sheer numbers: 80 percent of Colombians live within the Magdalena River basin. Thirty-eight million of the country’s 49 million people depend on its waters in one way or another. The river’s banks touch eleven of Colombia’s thirty-two distinct departments: Huila—where the Magdalena is born—then Tolima, Cundinamarca, Caldas, Boyacá, Antioquia, Santander, Cesar, Bolívar, Magdalena, and Atlántico, where it finally reaches the sea. The people of the Magdalena River valley live in communities as large as major cities with hundreds of thousands of inhabitants (Neiva, Barrancabermeja, Barranquilla) and as small as two or three fishing huts on patches of riverside land.

In between the extremes are towns and villages of varying sizes, whose inhabitants have jobs mostly related to the river and its surrounding land, in industries such as fishing, canoe transport, agriculture, and cattle ranching. There are a few who are able to eke out a living by promoting the river’s conservation—from leading community-based conservation and cultural preservation projects to working in local- and department-level government environmental offices—but not nearly enough. Apart from some notable exceptions, the financial situation is often dire, and in some cases, people do not have work at all, turning to more informal sources of income or subsistence fishing and farming in order to feed their families.

Many of the people who live along the banks of the Magdalena are also often among Colombia’s most vulnerable communities. Refugees from Venezuela fleeing a catastrophic situation in their home country continue to settle wherever they have family ties, unloading at dawn with their few possessions from the dark cover of idling cattle trucks draped with black tarps. Afro-Colombians, the descendants of enslaved people brought over from sub-Saharan Africa, live closer to the Caribbean coast in lands known for being the origin of the rousing rhythms and undulating accordion melodies of vallenato and cumbia music. And people of Indigenous origin populate the highlands of the Macizo Colombiano—the Colombian Massif—a geographical clustering of the birthplaces of the most important mountain ranges and rivers of Colombia that once allowed for the natural convergence of tribes from surrounding regions who used the river gorges as networks for trade and cultural diffusion.

After the first one hundred of its 950 total miles, the river ceases to tumble over smooth, gray boulders and exits the craggy massif, setting its course almost precisely due north, and quickly widening as it descends into the muggy lowland plains that have come to be known as the Magdalena River valley. For much of its course, the Magdalena flows through these lands—tierras calientes, steaming-hot valleys once draped with megadiverse jungles and unhindered savannas. Just before reaching the coast, the mountains on either side of the valley dissipate, and the river loses itself in a vast seven-thousand-square-mile mess of low-lying marshes and wetlands. It then regains its shape for its final hundred-mile run toward the Caribbean Sea.

Follow the Magdalena far enough upstream, however, and you get a very different picture. A narrow, raging torrent of water at this altitude, the river first leads you past the farms and pastures in the rolling hills, then upward through still-forested mountains via rain-slicked trails, and finally, higher yet into the treeless páramo landscape that is unique to the high South American tropics. This is where, at nearly eleven thousand feet above sea level, Doña Juana was supposedly swallowed by the Laguna. The only way to reach the Magdalena’s source is a two-day journey on horseback from the closest official settlement along its banks: a village of approximately ninety families called Quinchana.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Every Day the River Changes by Jordan Salama. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Catapult. Copyright © 2021 by Jordan Salama.

Jordan Salama

Jordan Salama's work has appeared in outlets including The New York Times, National Geographic, and Scientific American. A 2019 graduate of Princeton University, he lives in New York.