Celebrating Socially Engaged Fiction at the Aspen Words Literary Prize

A Report From the Inaugural Ceremony

When Lesley Nneka Arimah sat down with her collection What It Means When A Man Falls From the Sky, she thought: “I hope that people read this and learn nothing.” She didn’t wish for her fiction to have an eat-your-vegetables vibe, she explained onstage the Aspen Words Literary Prize last night: “I didn’t want to write this in a way thinking the West was my audience. I was writing for my Nigerian, or like I call myself, my Nigerian-ish, folks. It was very important on the page that I was writing for me, and not to educate.” It’s the particular burden of writers of color to be called on to educate just as much as they are called on to entertain, usually even more: as Jenny Zhang said in “They Pretend To Be Us While Pretending We Don’t Exist” in 2015: “Why are we so perversely interested in narratives of suffering when we read things by black and brown writers? Where are my carefree writers of color at?”

Some of us were there—and so were those who wanted to read us—at the first-ever Aspen Words Literary Prize. The Aspen Words Literary Prize is a $35,000 annual award in its first iteration this year, awarded for a work of fiction that “illuminates a vital contemporary issue and demonstrates the transformative power of literature on thought and culture.” So what, I asked the guests in attendance, was a contemporary issue that they’d like to see more of in fiction? The answers ranged from first-generation immigrants (Steven Tran), to mixed cultural experiences and biracial identity (Katie Raissian), to rural issues (Abby Koski), to female experience from a female point of view (Sarah Burns), but quite a few echoed Lesley’s statements: “I want to see more writing from writers of color that don’t require them to be emissaries,” Nadxi Nieto of PEN America said. Alia Hanna Ahbib, a member of the Aspen Words Creative Council, said how she wanted more books that allowed writers of color to be playful, mentioning the playfulness of form and voice in How To Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia. Zinzi Clemmons, a finalist, told me she’d love to see stories that are surprising being told by people of color, instead of the traditional narratives that the publishing industry would expect.

Nothing about the Aspen Words Literary Prize was traditional, and hearing these responses from attendees made me so hopeful and excited for the future of literature, and where it could go if publishing would just listen. I was lucky enough to be asked to be part of the selection committee for the Aspen Words Literary Prize this first year, meaning that I was in the first tier of judges who read the 144 nominated books to narrow them down to the shortlist for the Prize Jury. It was a lot of reading, even for someone who reads compulsively, but a quite joyful task, especially seeing the diverse, dazzling longlist come together.

The finalists were What It Means When A Man Falls From the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah, What We Lose by Zinzi Clemmons, Exit West by Mohsin Hamid, Mad Country by Samrat Upadhyay, and Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward. These books took up most of my 2017; I read them in cars and on the subway, on vacation, on residency, at work, and at home, and it felt very full-circle to walk into The Morgan Library on this Tuesday night to celebrate the prize and the progress. There’s never been an easier party to get champagne at, by the way: always an excellent sign when you enter an event. We had a half an hour to clink flutes before making our way into the plush red seats of the auditorium to hear a Q&A and reading from the finalists, before the award was to be announced that night.

“I welcome your tote bag jokes,” Linda Holmes of NPR’s ‘Pop Culture Happy Hour’ announced as she got on stage to emcee. New president of the Aspen Institute Dan Porterfield took the stage next, explaining about how “the prize recognizes a work of fiction and the work of fiction.” Next Michel Martin emerged from backstage to moderate a discussion with the finalists. Mohsin Hamid and Jesmyn Ward were not able to make it because of scheduling conflicts, but three luminous finalists graced the stage: Lesley Nneka Arimah, Samrat Upadhyay, and Zinzi Clemmons.

Lesley Nneka Arimah, in a soft, sparkly jumpsuit, was cheerful and exuberant as she explained why she writes. “Writing satisfies something inside of me that nothing else does,” she said. Samrat Upadhyay, dapper in a dark suit, chimed in, “I’m a writer because it allows me to inhabit other people’s worlds and minds. Writing allows me to enter these spaces I couldn’t enter in my own life and body. And literature allows me to do the same thing.”

Zinzi Clemmons was in a gold beaded collar that made me clutch my bare neck in envy. She spoke about writing about the mixed-race experience. “When you are in the middle,” Zinzi explained, “there’s a lot of fighting about which side you belong to.”

The Q&A was being live streamed, and Martin ended by asking our finalists what advice they would give to young writers who might be watching.

Samrat offered, “The road is long so prepare yourself for the long haul. Read a lot and keep reading as many different kinds of books as you can.”

“To young female African writers especially,” Lesley said, “there is nothing that you will do that will ever cushion you from criticism and make you happy, so misbehave. Write all of the things you want to write that you know will disappoint people. Be radically honest with yourself and everyone else.”

“The things you may be self conscious about now, or what people don’t like about you when you’re starting out, will be what people applaud you for later on,” Zinzi said.

Each finalist gave a reading (three in person, two via video screen), before receiving their framed citations from Prize Jury member Phil Klay. (When I asked him later on what issue he’d like to see more of, he laughed, “I’ve got a dog in the fight!” He writes about his experience in the US military policy, but he said he’d especially like to see more work in translation, and recommended Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi.) Adrienne Brodeur and Jamie Kravitz took the stage to finally announce the prize, though not before thanking everyone involved. And the winner was: Mohsin Hamid for Exit West. Though we didn’t think he was in the room, Rebecca Saletan of Riverhead assured us he’d used one of his own magic portals to read us his thanks, and the ceremony ended as we watched Hamid read in front of a cartoon doorway surrounded by stars. We drank more wine, picked at large slabs of cheese and crackers, and mingled before going home home, thinking of which portal we’d enter next: hopefully something transformative and carefree.

The finalist books

The finalist books

Onstage Q&A

Onstage Q&A

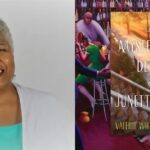

The Aspen Words Literary Prize itself

The Aspen Words Literary Prize itself

Mohsin Hamid accepts his award

Mohsin Hamid accepts his award

Rebecca Saletan

Rebecca Saletan

Michel Martin, Lesley Nneka Arimah, Zinzi Clemmons, Samrat Upadhyay

Michel Martin, Lesley Nneka Arimah, Zinzi Clemmons, Samrat Upadhyay

Michel Martin, Lesley Nneka Arimah, Zinzi Clemmons

Michel Martin, Lesley Nneka Arimah, Zinzi Clemmons

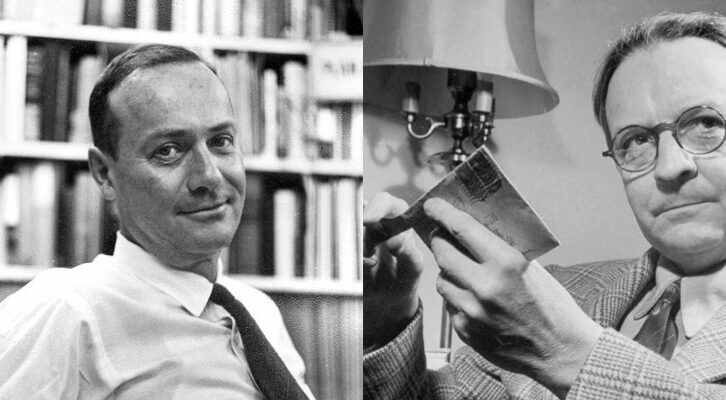

Samrat Upadhyay

Samrat Upadhyay

Abby Koski, Steven Tran

Abby Koski, Steven Tran

Stephanie Buschardt

Stephanie Buschardt

Linda Lehrer, Brittany Stauch

Linda Lehrer, Brittany Stauch

Adrienne Brodeur

Adrienne Brodeur

Rebecca Saletan, Idra Novey

Rebecca Saletan, Idra Novey

Phil Klay

Phil Klay

All photos courtesy of Erin Baiano.

Kyle Lucia Wu

Kyle Lucia Wu's debut novel Win Me Something is out now from Tin House Books. She is the Programs & Communications Director of Kundiman and a former Asian American Writers' Workshop Margins Fellow.