Capturing the Soul of Fire Island: Attitude Without Judgment

Patrick Ryan on the Photography of koitz

My first trip to Fire Island began like something out of a gothic novel. I was summoned at the last minute, on a gloomy Friday, to join friends out in Cherry Grove. I couldn’t leave until evening, which meant I was going to be part of the mass exodus filing out of Manhattan for the weekend. Already regretting having accepted the invitation, I rushed home after work, overstuffed my backpack with clothes and books, took the subway to Penn Station, pushed my way onto the Long Island Railroad, then dropped into a seat and closed my eyes.

It started raining. The wind picked up. Water slapped against the window where I was resting my head. I had to dash through the downpour to switch trains midway through, and dash again in Sayville, where I barely made the shuttle bus that would take me to the ferry landing. I don’t know if it was due to the weather or my mood or a shared dampening of spirits, but the dozen or so people I waited with on the landing—some with dogs, some dragging family-sized ice chests—looked funereal. The sun had gone down. It was chilly for August. And it was still raining.

But then the ferry blew its horn and emerged out of the darkness.

Halfway across the Great South Bay, the rain turned to mist. By the time we were approaching the outer barrier islands, the mist had become a dense, moving fog, and the lights that appeared out of the darkness looked as hazy and ephemeral as dandelion blooms.

Doug—one of the friends who’d invited me—was waiting on the dock. He was dressed in shorts and flip-flops, a straw fedora raked back on his head, and he looked decidedly unfunereal. I thanked him for inviting me and for coming out to meet me. He waved it off. I asked him if he was soaked and freezing. He waved that off too. He told me to relax, told me everything was fine, and he waved his hand again as if trying to fan away all the Manhattan I’d brought with me. As I walked with him up the dock, I noticed that none of the people I’d ridden the ferry with seemed glum anymore. They were smiling, greeting friends, some of them even laughing about the weather.

“Brock in a Dress. Grove Hotel. Cherry Grove, 2015.” Photograph by koitz

“Brock in a Dress. Grove Hotel. Cherry Grove, 2015.” Photograph by koitz

I followed Doug along a network of elevated boardwalks into Cherry Grove. There were snippets of music and voices along the way, and porch lights glowing here and there, but you could barely see your hand in front of your face. “Watch out for deer,” Doug said.

“On the boardwalk?”

“Yes. They’re insane. They’ll kill you.” He laughed. “Don’t fall off the side, either. It happens all the time out here, and it’s not pretty.”

The question on Fire Island is always why not?

The house he shared with his partner, Koitz, was warm and cozy. Art Tatum was on the stereo. I was asked to remove my shoes and was handed a glass of wine. Food appeared—I would say, “as if by magic,” but I knew better, having seen those ice chests being dragged onto the ferry; to eat on Fire Island, you either have to pay through the nose or bring it with you. Before long, there was a knock at the door: neighbors bearing dessert, and more wine.

I drifted off to sleep on the couch that night, listening to the wind rustle the trees.

*

The next morning, the sky was clear and so bright there was hardly any blue in it. I was the first one up in the house, so I made coffee, carried a mug outside and took a walk, shirtless, bound for the beach. The island was skinny, barely a quarter of a mile wide; how hard could it be to find the beach? Not hard at all, it turned out. I passed people on the boardwalk, people sweeping their porches, people on the stairs leading down to the sand. Some were young, some were old, some were middle-aged (like me). And every one of them said or at least nodded hello. Can they tell I’m a first-timer? I wondered. (It would take all of a day for me to figure out that there only needs to be one common circumstance for cordiality on Fire Island: you need to be a person on Fire Island.)

I strolled the beach. I met an old man with a golden retriever, a lesbian couple with a corgi, a young man with a hangover and two vials of 5-Hour Energy Drink tucked into the waistband of his speedo. I passed a man doing yoga or tai chi—he was facing the ocean, standing on one leg with his arms outstretched—and even he nodded hello.

“Invasion 2009.” Photograph by koitz

“Invasion 2009.” Photograph by koitz

Because I have the sense of direction of a gnat, I got lost trying to find my way back to the house. But I was in such a good mood that I didn’t care. I just kept walking on the boardwalk, turning left, turning right, passing what seemed like hundreds of little houses and plenty of friendly people, until the boardwalk ran out and I was in the sand, then in the woods, then on the boardwalk again. I discovered a dock that was different from the one I’d arrived at the night before. I discovered a bar filled with shirtless men having brunch. I discovered a grocery store, where they sold me an overpriced croissant but let me refill my coffee mug for free. I kept walking, and kept finding things I wanted to see. Eventually—and purely by accident—I found my way home.

Fire Island, I’ve concluded, is attitude without judgment.

While Doug rooted through his closet looking for aloe vera lotion (I was sunburnt to the color of a Slim Jim), Koitz unlaced the coffee mug from my fingers, handed me a glass of water, and said, “So you walked from here to the beach, then through the Meat Rack to the other end of the Pines, then back through the Pines and the Meat Rack to the Grove?”

“I guess,” I said.

“You’re fucking crazy,” he said. “You’re lucky you didn’t die from sunstroke.”

Not only had I not died, I told them; I’d been invited to karaoke by a pixie-like young man handing out fliers. And I’d been invited to brunch the next day by a drag queen. And to High and Low Tea—two different events, thank you very much. And to top it all off, someone had invited me to an Underwear Party that very night. “Is that a real thing?” I asked my hosts. “People just walk around in their underwear?”

Doug, holding the bottle of aloe vera, began to cackle. Koitz rolled his eyes.

*

Fire Island, I’ve concluded, is attitude without judgment. It is attitude plucked free of the sticky hands of snark and delivered gently back to its original meaning. A settled way of thinking. A settled way of feeling. A settled way of receiving what the ferries deliver. Fire Island is c’est la vie meets bring it on.

Koitz has been photographing people on Fire Island for the past fourteen years. In addition to their artistry, what makes these photographs so celebratory is that they capture the spirit that has everyone welcoming the next ferry, the spirit that makes some of us dress in drag, or as pixies, or as house-blessing nuns, the spirit that allows some of us to dress as a framed Mona Lisa at happy hour and some of us to undress in places where we might otherwise have stayed covered up. A crowd at Low Tea, captured from above with fading light and a long exposure, looks as graceful and slippery as a school of koi. A pair of go-go boys, dancing in the foreground as Valley of the Dolls is projected onto a sheet behind them, looks simultaneously like dolls before giants and giants before dolls. A pack of friends wandering through the Meat Rack at night becomes an impromptu birthday party that is transformed, through Koitz’s lens, into a stolen moment from A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

“Happy 4th of July, IndepenDance, FIP 2013.” Photograph by koitz

“Happy 4th of July, IndepenDance, FIP 2013.” Photograph by koitz

We’re all something when we’re not on the island. We’re teachers and administrators and housekeepers; we work in retail and finance and construction; we’re acupuncturists and nurses, plumbers and fund-raisers. But when we’re on the island, we’re only one thing: people on Fire Island. Koitz has produced a body of photographs that are somehow both candid and stylized, often as hilarious as they are titillating. Put together, they form a portrait of what some might call bacchanalia and others might call harmonious indulgence. I call it happiness—or, at the very least, the suspension of worry. For the question on Fire Island, as these photographs show, is never why? The question on Fire Island is always why not?

__________________________________

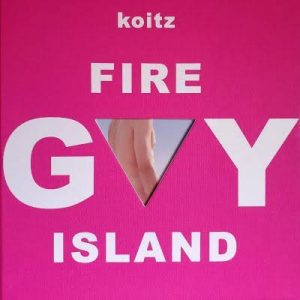

koitz Gay Fire Island by koitz is available for purchase online.

Patrick Ryan

Patrick Ryan is the author of the novel Buckeye. He is also the author of the story collections The Dream Life of Astronauts (named one of the Best Books of the Year by the St. Louis Times-Dispatch, Lit Hub, Refinery 29, and Electric Literature, and longlisted for The Story Prize) and Send Me. His work has appeared in The Best American Short Stories, the anthology Tales of Two Cities, and elsewhere. The former associate editor of Granta, he is the editor of the literary magazine One Story and lives in New York City.