The university also gave me a coupon book with vouchers for food. There weren’t many, and I spent them all, without fail, the first week of every month. Sometimes I’d take my mother out for Chinese and pay the bill with vouchers. Otherwise I used them up myself. I’d go to classes, then at lunchtime I’d walk around downtown to see which places would accept the vouchers. One day I made a list of all the restaurants where I could use them. And I started to visit them, in Providencia, downtown, around Central Station. The action never varied much: I’d go in, sit down at an isolated table, and eat. And the vouchers never lasted past the first week of the month.

* * * *

I imagine the deserted beaches. The sun beginning to set. The red ocean. The orange sky. Those places I’d gone with my family before I had a memory. Before the accident. The images don’t exist outside of a few faded photos. But that’s how they described it to me. The deserted beaches and my family, camping out for a couple of weeks. My father, my mother, my grandparents, and my Uncle Neno.

* * * *

I also got a cash stipend. Fifteen thousand pesos a month. Sometimes I would save up for two or three months to buy clothes so I wouldn’t need so many things when I went to Iquique. Once, I saved up money to buy a microphone and a tape recorder. And I started recording my voice at night, before I joined my mother in bed. I wanted to be like those espn commentators who did the Champions League when I was little and still living in Iquique. Like the one who reported on the final between Manchester United and Bayern Munich at the Camp Nou stadium. Supposedly he was Chilean, but his accent sounded neutral to me. And at night I used to practice that accent, trying to come up with nicknames for every Chilean player. And I’d remember that final match, that period in Iquique when my mother was working and I spent the days alone, watching the 1999 Champions League games.

* * * *

The color of the sky: orange, maybe purple at times. The desert: blue, as if a blanket were covering it. There is nothing. My father is listening to another cd, a group I don’t know. In the back, the woman and her son are talking in low voices. The desert looks as if it were going to sleep, tucked in under a blue blanket. And in the distance, a village. Some houses. Chacabuco. There’s a man at the entrance to the town. He’s drinking something from a cup while he watches the cars pass on the highway. Or that’s the impression I get, at least. My dad tells me he must be crazy. The town is deserted. There are no lights; there is nothing and no one. Just the man at the entrance and the houses that blend in with the desert. My dad says it again, but I don’t reply. I have my headphones on. He says the man hears voices, or that’s what they say; his story is well known. I don’t take my eyes off the desert. We leave the man behind. My father starts to tell me the story, but I’d rather not listen. And I imagine the man drinking the last sip from his cup and going to sleep in a house lit by a couple of candles. He waits for them to burn out, closes his eyes, and sleeps. “Surrounded by whispers,” says my father. “The nightmares and shouts and whispers of all those people,” he says, and I close my eyes while night falls in the desert.

* * * *

Once, I got to watch that final between Manchester and Bayern again. And what I did was turn the volume down and start announcing the game. I tried to forget how it ended, though that was impossible. I related the first half calmly, until Bayern went confidently into halftime, ahead by one goal. The second half, as the Chilean announcer would say a few minutes later, was not for the faint of heart. When Lothar Matthäus was subbed out in the eightieth minute, I stood up and started clapping. Just then my mother came into my room and saw me there, in front of the tv with the microphone and recorder, giving a standing ovation. I motioned for her to leave, and she did. Finally, at minute ninety-one, the story began to change. A corner and a goal by Teddy Sheringham. I yelled so loudly my mother came back into the room and stood there watching the scene: I was shouting, trying to articulate a coherent, stirring story. I was on the verge of tears. And then came the end, a minute later, when Ole Gunnar Solskjær, the baby-faced killer, the greatest replacement of all time, blocked a ball in the box and brought glory to Manchester, to England, an entire country watching its team turn that scoreboard around. An epic story, a match for the ages, damn good soccer.

* * * *

The final stretch. Alto Hospicio. Lights in the darkness. Streets lit with low-intensity bulbs. Two women walking along the edge of the highway. One of them puts out her thumb. My father drives in silence while his family sleeps. When I left Iquique, Alto Hospicio didn’t yet exist. There were five houses in the middle of the desert, along with a couple of illegal garbage dumps. Now it’s a city, I think to myself, a city with lit streets. My father turns on the radio and manages to pick up an Iquique station. A man is talking about a fire. There are no fatalities, only injured people, the announcer says as we start to descend from the hills into Iquique. Lights that move away from a black stain: the ocean. A few dots scattered in the black stain, around the port. The soccer stadium with its field lit up. The yellow city, us going down, the family awake now, and the man on the radio who leaves us with a song by Amerikan Sound. My father turns off the radio and tells me we’ve arrived. I nod, thinking I should call my mother; I don’t want to.

* * * *

I also practiced doing an interview program. I asked the questions, and I answered them too. The idea was to put myself to the test, so I tried to give complex responses that might make me draw a blank. I wanted to gauge my ability to react and improvise, the way my professors had recently taught me. It lasted a couple of episodes, then my mother came in and asked me why I didn’t interview her.

That was the start of the interviews. That was the start of the stories.

* * * *

We’re in Iquique. We go to my grandpa’s house. That’s where I’ll be staying for summer vacation. It’s strange to go inside and not find my grandmother there. The house seems bigger. It smells musty, unaired. My grandpa comes out to greet me. He’s wearing an apron. Then he looks me over and tells me I’m very fat, that I need to take care of myself. I don’t say anything. I go to the master bedroom. The portrait of my grandmother is still hanging on the wall. I leave and go sit down at the table. My father is telling my grandpa about our trip to Buenos Aires, the wonders of the Buenos Aires trip. Nancy is sitting next to him with her son. They smile while my dad tells my grandpa that he bought me some books. He looks at me, and I smile back and tell him yes, he bought me three books. Then my dad leaves, and I’m alone with my grandpa, in silence.

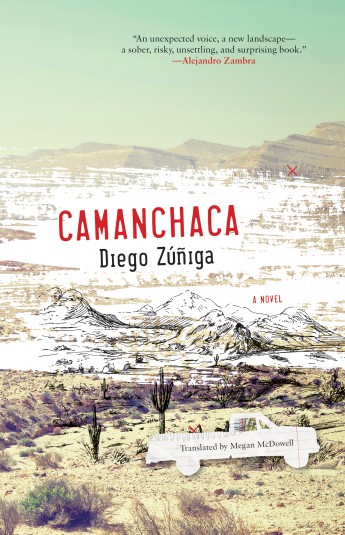

This excerpt is reprinted by permission from Camanchaca (Coffee House Press, 2017). Copyright © 2017 by Diego Zuñiga. Translation copyright © 2017 by Megan McDowell.