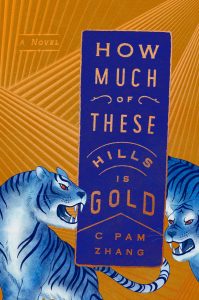

C Pam Zhang on Writing in a Time of Grief

"That mountain is not insurmountable."

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

A few years ago, a friend I had known only as a writer posted a picture of freshly baked bread. The loaves were golden and buoyant, in stark contrast to the caption. The writer declared the bread the physical manifestation of procrastination from their book project. The bread was shame. The bread was self-flagellation. The bread was the modern confessional, dank and musty, though at first glance it looked only delicious. I was, at the time, mired in my own writing-related shame and the bread inspired deep feelings of inadequacy. I typed off a defiant joke.

BREAD IS WRITING!! I said.

I would make variations of this joke over the next few years. Netflix is writing! I said, or Cocktails are writing! Photos of my cat are writing! At some point the exclamation marks, and the irony, peeled away. Flowers are writing. Baths are writing. Doing nothing is writing.

Two weeks ago, I intended to compose a meticulous newsletter on craft. I felt prepared for the task, given my recent experience with the orchestrated process of publishing a book. I’d gone through countless drafts, juggled schedules and steps and spreadsheets. I emerged with a toolbox I was rather proud of. This is the hammer I take to revision. This is the chisel with which I carve scenes. This is the sound-editing software with which I play sentences back to myself to interrogate their sonic qualities.

That was two weeks ago. Now my tools look like a child’s toys, absurdly unsuited to the scale of the moment. An earthquake has rumbled through me with every fresh wave of news, and I can’t possibly confront the rubble with a chisel or Audacity. Craft is inadequate. I am—as many of us are—facing the mountain that is grief.

Listen, friends. That mountain is not insurmountable. I’ve crossed it before. I was twenty-two when my father died and then, as now, I wanted control. I wasted hours reading bad articles about the stages of grief. I wasted even more hours trying to write about my father. Both obsessions slunk from the same lizard part of my brain that tried to shelter under the illusion of structure, that scuttled after anything with momentum. Stages, paragraphs, outlines—I wanted the reassurance that grief had a roadmap I could follow.

I am sorry to say that you cannot write yourself through grief. Would that we could. Would that we could design our sentences and syllables, our powerful metaphors and efficient engines of plot, into machines, armored tanks that carry us through the wilds of grief and deliver us unscathed to the other side. Twice in my life I’ve tried to armor myself in writing, because writing was how I made sense of the world. Twice have I gritted my teeth through the death of a loved one and churned out bad pages in response. I was trying to force meaning when there was none, when I was too close for meaning.

It’s a shame that when we say writing, we mean only the act of putting words on the page. How dull. How short-sighted.

Imagine this:

It is one year ago and we are still hugging our friends, still swaying en masse from subway poles, still stopping for golden-lit happy hours at outdoor cafes where we lick food from our fingers and laugh in each other’s faces and never disinfect our hands. On the evening of a day such as this, I write an email to a friend. I share my life, inquire about hers. I ask about her lover, her job, her health. We haven’t corresponded in months and so as I write there is a sense of stiff muscles warming. Only at the very end, when I feel sufficiently tender, do I say, I hope the writing is going well.

To an outsider, this statement might sound cold. Writers know it as anything but. When I say, I hope the writing is going well, I am saying, I hope you are able to access the truest part of yourself; I am saying, I hope you feel thrillingly alive to possibility; I am saying, I hope you feel human.

We come to the page when, turning back to face the mountain, we are far enough that we can finally discern the shape of it that was ungraspable from the peak. Then you can breathe and rest; then you can appreciate the loveliness of the moon, the syllable. You can take out your chisel and your hammer, which were never lost; you have all the time in the world to make, in miniature, a piece of art that captures the wilds of your grief. Until then, you are allowed to be tired, you are allowed to be footsore and heartsick, you are allowed to lay down your pen and focus on survival. I say to you, I hope the writing is going well. By which I mean:

Walking is writing. Crying is writing. Talking to a parent whose health you fear for is writing. Cooking is writing. Lying prostrate on the rug and watching sun stripe the wall is writing. Your lover’s hand on yours is writing. Your dog is writing. I have had years in which I could not see the shape of my life or string together a good sentence; and I have had a summer in which, three years late, the fog lifted in a different climate and suddenly I could write about my father. Don’t force the words. They will come, like old friends. You do not have to walk on your knees / for a hundred miles. If you are grieving, then I give you permission to write in the best way you can—which is to say, to live.

*

Read more on writing through grief:

Naja Marie Aidt on creating meaning from the meaningless of grief.

Writing the impossible grief of very young widowhood.

When writing is your job, researching trauma can be a workplace hazard.

T Kira Madden, against catharsis: writing is not therapy.

Jayson Greene on the risks of writing about grief.

*

5 Books About Grief

RECOMMENDED BY C PAM ZHANG

Helen Macdonald, H is for Hawk

Toni Morrison, Beloved

Ali Smith, How to Be Both

Mira Jacob, Good Talk

Brandon Taylor, Real Life

__________________________________

How Much of These Hills Is Gold by C Pam Zhang is available via Riverhead.