Book Tour in the Early Days

of Coronavirus

Gabriel Bump on the Surreality of Recent History

What strange things: going outside, getting on planes, different hotels, seeing my parents, getting drinks at a bar, driving down familiar roads with past versions of myself.

I had expected some personal growth while on book tour. I was prepped for the exhaustion. I leaned into the constant movement. I’d count the cities, smile at the days-long break, where I’d sleep in my own bed, stand in my own shower for a few minutes longer than necessary.

Before the first plane ride on February 5, from Buffalo to New York City, I paid half-attention to a pandemic creeping into the United States.

The first confirmed COVID-19 case in New York City would come almost a month later. Almost a month after that the subways passed along underground empty, except for people without the privilege of working from home and sheltering in place.

That long ride from Manhattan to Queens, to see my sister and nephew, eating dumplings. That was a world ago: hugging, touching, promising to come back soon, watching my nephew cry against going to bed, hearing my sister shush behind a closed door.

*

On the planes from Buffalo to Detroit, Detroit to St. Louis, I imagined writing something about the whole experience.

Debut authors are advised to write essays, let people know about you, introduce yourself, poke your head above the fray and distinguish your voice from the other voices, get people excited.

Hugging my parents goodbye, kisses on the cheek. My father heading off to work at the hospital.

I had two events in Missouri. One in St. Louis. One in Columbia, where I attended the University of Missouri for two years, before dropping out, crashing out.

I figured I would write about coming back to a place for the first time in years—how I’d changed, how the place had changed, how I kicked a cigarette habit years ago, how I’d smoke a pack a day in college, how the first thing I did in St. Louis was buy Marlboro Lights, how I smoked two late one night, back-to-back, how I kept the pack in my bag, untouched for the remainder of tour, how they’re in my bedroom now, on my bookcase, untouched.

I would write about the drive from St. Louis to Columbia, down Interstate-70. I would write about how, one night, almost ten years ago, during my sophomore year, I was driving down Interstate-70 with my girlfriend, our dog, and a friend.

I would write about how I fell asleep at the wheel going 70 miles an hour.

I would write about waking up to the passengers shouting my name, driving into a ditch, totaling the driver’s side, kicking my door open, calling the authorities, the authorities coming, the authorities saying they smelled weed in the car, the tow truck coming, the authorities following the tow truck and us, three brown-skinned teenagers and a white dog.

We sat in the tow yard, in the tow truck, while the authorities went through my totaled car, threw my books on the dirt, opened our bags, spilled our clothes. The authorities came back to the tow truck with an old roach in his palm, disappointed they didn’t find more, ounces and pounds. He charged me with misdemeanor possession. He also charged my girlfriend with possession after she offered to take the charge, knowing I was already on probation in Boone County, a few counties over, due to underage drinking tickets and a fake ID.

I would write about the white tow-truck driver giving us a ride back to Columbia, how he said it wasn’t fair, how he was sorry, how he wished us well.

I would write about driving down that highway, older now, during a soft snowstorm, unable to remember the crash site. I would write about how that experience solidified my fear of death, my distrust of authorities.

I had a reading in Milwaukee in a few weeks. There was a Chicago book festival in early summer. I’d see her soon.

I would write about Columbia. How the last time I was there, a judge said he was sick of seeing me. If he ever saw me again, he’d throw me in jail. How I was back, reading from my book, staying out of trouble, exhausted. How I gave a reading to four people during a snowstorm. How I went back to the hotel and was asleep before ten. How I wanted the judge to see me now.

There was the St. Louis airport, a day later, a delayed flight, further delays. I would write about how I was trapped in Missouri, again.

*

What about days later, when I escaped Missouri, when I was back in Chicago, walking into the Seminary Co-Op bookstore in Hyde Park? The packed room. Those teachers and friends and family and strangers sitting right there, quiet, listening to read. It was enough to make me cry. I would write about crying in public, how there was no stopping it. I would grapple with the words to describe the impulse. The teachers, proud of me. My parents, proud, making me sign books for their friends. How it hit me, then, reading in that bookstore. How the person I’m now is different from the child they knew. How they were worried about me. Those missed assignments, the average grades, the waywardness. How they weren’t worried now. It’s enough to make you cry. All that relief looking back at you, listening, applauding, hugging you.

Hugging my parents goodbye, kisses on the cheek. My father heading off to work at the hospital. Hugging my mother, again, at that airport. Saying I’d see her soon. I had a reading in Milwaukee in a few weeks. There was a Chicago book festival in early summer. I’d see her soon. Then she kissed me on the cheek again and drove to work at a hospital.

*

A break in Buffalo. Days on the couch. Teaching my workshop Monday night at the University at Buffalo. Apologizing for my delayed e-mails, promising a return to normalcy, how I’m tired and scatter-brained, how the tour is almost wrapped up, how–after Boston, Western Massachusetts, and Washington D.C.–I’d have two weeks back home.

After my reading in Boston, I imagined writing about the drive to Western Massachusetts, how I took Route 2 instead on the Mass Turnpike, how the last time I drove westward down Route 2, I wanted to drive my car off the road.

I went to grad school at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, spent four years in verdant hill towns. One day, a year after graduation, in spring, I was sad and isolated like any other day because all the days are sad and isolated. Then the sadness was replaced with numbness. Then the numbness turned heavy. The next day, I thought about sitting in the bathtub and slitting my wrists. I curled up in bed and shook and told myself no, no, no, no. I wouldn’t do it. I couldn’t do it.

I was teaching creative writing classes in Boston. I’d drive back home on Route 2, about two hours in darkness. I’d feel heavy. I’d feel myself accelerating into curves, wanting to keep on straight, wanting to crash. I’d slow down. The slowing down remains a frightening mystery. I still don’t understand what stopped me from going straight.

Two years ago, the heaviness turned suffocating. Here’s another frightening mystery: instead of killing myself, I packed a bag, loaded up my car, and drove to Chicago. I don’t remember much of the following weeks. It was May. I slept on friend’s couches, stayed at my parents’ place, told everyone I was fine, better, getting better, don’t worry, don’t worry. I spent my 27th birthday alone in a Cleveland AirBnb. I took my book advance and rented an apartment in Buffalo. I wanted to live in a place without familiar faces. I wanted to write my next book without distractions. I wanted solitude. I wanted to wade through my depression and see if I came out the other side.

Back on Route 2, driving to my hotel in South Hadley, I thought I’d write something about driving slow and minding my curves, how that felt like a monumental victory, how I couldn’t believe it, how lucky I felt. How I was alive and wasn’t that wonderful. How I cried that night, reading alongside Jeff Parker, my friend and mentor. Dammit, wasn’t that lucky.

How traffic on the Mass Turnpike was inching forward the next morning. How the anxiety of missing my flight to D.C. was dwarfed by joy. All that relief radiating on the highway.

*

I didn’t know that reading in D.C. was my last for the foreseeable future. How precious the dinner with a friend from Chicago beforehand would feel weeks later, now. How I hugged Brandon Taylor after our reading, how we wished each other luck, how we had fun. How could I know how precious that hug would feel weeks later.

I believe it’s important to remember ourselves before this: how we’re changed, how we’ve grown, how tragedy and terror can break us and turn us into something new, how the breaking can heal; how what makes us cry, those hugs we gave, those times we crashed, those times we sped up, those moments life didn’t seem worth it; how it all adds up to a strange faith in the future. How we lived before and we’ll live again.

__________________________________

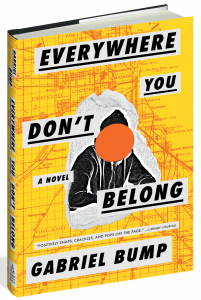

Everywhere You Don’t Belong by Gabriel Bump is available now via Algonquin Books.

Gabriel Bump

Gabriel Bump, author of Everywhere You Don't Belong, grew up in South Shore, Chicago. His nonfiction and fiction have appeared in Slam magazine, the Huffington Post, Springhouse Journal, and other publications. He was awarded the 2016 Deborah Slosberg Memorial Award for Fiction. He received his MFA in fiction from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He lives in Buffalo, New York.