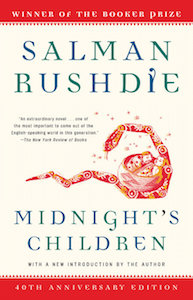

Bollywood or Bust: Salman Rushdie on the World of Midnight’s Children,

Forty Years Later

“I wanted to write a novel of vaulting ambition, a high-wire act with no safety net, an all-or-nothing effort.”

The first thing to say on the 40th anniversary of Midnight’s Children is that I’m more than glad it is still finding readers, who are still finding something of value in its pages. Longevity is the real prize for which writers strive, and it isn’t awarded by any jury. For a book to stand the test of time, to pass successfully down the generations, is uncommon enough to be worth a small celebration. For a writer in his mid-seventies, the continued health of a book published in his mid-thirties is, quite simply, a delight. This is why we do what we do: to make works of art that, if we are very lucky, will endure.

As a reader, I have always been attracted to capacious, large-hearted fictions, books that try to gather up large armfuls of the world. When I started to think about the work that would grow into Midnight’s Children, I looked again at the great Russian novels of the 19th century, Crime and Punishment, Anna Karenina, Dead Souls, books of the type that Henry James had called “large, loose, baggy monsters,” large-scale realist novels—though, in the case of Dead Souls, on the very edge of surrealism. And at the great English novels of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Tristram Shandy (wildly innovative and by no means realist), Vanity Fair (bristling with sharp knives of satire), Little Dorrit (in which the Circumlocution Office, a government department whose purpose is to do nothing, comes close to magic realism), and Bleak House (in which the interminable court case Jarndyce v Jarndyce comes even closer). And at their great French precursor, Gargantua and Pantagruel, which is completely fabulist. I also had in mind the modern counterparts of these masterpieces, The Tin Drum and One Hundred Years of Solitude, The Adventures of Augie March and Catch-22, and the rich, expansive worlds of Iris Murdoch and Doris Lessing (both too prolific to be defined by any single title, but Murdoch’s The Black Prince and Lessing’s The Making of the Representative from Planet 8 have stayed with me).

But I was also thinking about another kind of capaciousness, the immense epics of India, the Mahabharata and Ramayana, and the fabulist traditions of the Panchatantra, the Thousand and One Nights, and the Kashmiri Sanskrit compendium called Katha-sarit-sagar (the “Ocean of the Streams of Story”). I was thinking of India’s oral narrative traditions, too, which were a form of storytelling in which digression was almost the basic principle; the storyteller could tell, in a sort of whirling cycle, a fictional tale, a mythological tale, a political story, and an autobiographical story, he—because it was always a he—could intersperse his multiple narratives with songs and keep large audiences entranced. I loved that multiplicity could be so captivating. Young writers are often given a version of the advice that the King of Hearts gives the White Rabbit in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, when the Rabbit becomes confused in court about how to tell his story: “‘Begin at the beginning,’ the King said, very gravely, ‘and go on until you come to the end; then stop.’” It was inspiring to learn, from the oral narrative masters of, in particular, Kerala in South India, that this was not the only way, or even the most captivating way, to go about things.

I wanted to write a novel of vaulting ambition, a high-wire act with no safety net, an all-or-nothing effort: Bollywood or bust, as one might say.

The novel I was planning was a multigenerational family novel, so inevitably I thought of Buddenbrooks, and, for all its nonrealist elements, I knew that my book needed to be a novel deeply rooted in history, so I read, with great admiration, Elsa Morante’s History: A Novel. And, because it was to be a novel of Bombay, it had to be rooted in the movies as well, movies of the kind now called “Bollywood,” in which calamities like babies exchanged at birth and given to the wrong mothers were everyday occurrences, and things like the “indirect kiss” invented in my novel’s imaginary film The Lovers of Kashmir actually did happen. There were two movie songs in my head: from Raj Kapoor’s film Shree 420, the song “Mera Joota Hai Japani” (“My Shoes are Japanese”), a happy paean to hybridity, and from the film C.I.D. the immortal “Bombay Meri Jaan” (Bombay My Darling), as much the anthem of the city of my birth as “New York, New York” is of the city where I now live. If a novel could have a soundtrack or a Spotify playlist, the Midnight’s Children collection would have to have these songs on it, as well as a Faiz Ahmad Faiz ghazal, and, perhaps, the school song of Bombay’s Cathedral School, where I was a student, and so was Saleem Sinai: Prima in Indis, gateway of India, Door of the East with its face to the West . . . another ode, you see, to Bombay.

As you can see, I wanted to write a novel of vaulting ambition, a high-wire act with no safety net, an all-or-nothing effort: Bollywood or bust, as one might say. A novel in which memory and politics, love and hate would mingle on almost every page. I was an inexperienced, unsuccessful, unknown writer. To write such a book I had to learn how to do so; to learn by writing it. Five years passed before I was ready to show it to anybody.

For all its surrealist elements, Midnight’s Children is a history novel, looking for an answer to the great question history asks us: What is the relationship between society and the individual, between the macrocosm and the microcosm? To put it another way: Do we make history, or does it make (or unmake) us? Are we the masters or victims of our times? Saleem Sinai makes an unusual assertion in reply: He believes that everything that happens, happens because of him. That history is his fault. This belief is absurd, of course, and so his insistence on it feels comic at first. Later, as he grows up, and as the gulf between his belief and the reality of his life grows ever wider—as he becomes increasingly victim-like, not a person who acts but one who is acted upon, who does not do but is done to—it begins to be sad, perhaps even tragic. (During the writing, I became frustrated by Saleem’s growing passivity, but whenever I tried to write a scene in which he took charge of events it was unconvincing, and in the end I accepted that he had to be who he was, and I couldn’t make him something I might have preferred him to be.)

Forty years after he first arrived on the scene—forty-five years after he first made his assertion on my typewriter—I feel the urge to defend his apparently insane boast. Perhaps we are all, to use Saleem’s phrase, “handcuffed to history.” And if so, then yes, history is our fault. Many people—Thomas Jefferson, Alexis de Tocqueville, H. L. Mencken—are credited with some variation of the notion that “people get the government they deserve,” but maybe it’s possible to make an even broader assertion and say that people get the history they deserve. History is not written in stone. It isn’t inevitable or inexorable. It doesn’t run on tramlines. History is the fluid, mutable, metamorphic consequence of our choices, and so the responsibility for it, even the moral responsibility, is ours. After all: If it’s not ours, then whose is it? There’s nobody else here. It’s just us.

If Saleem Sinai made an error, it was that he took on too much responsibility for events. I want to say to him now: We all share that burden. You don’t have to carry all of it.

The question of language was central to the making of Midnight’s Children. In a later novel, The Ground Beneath Her Feet, I used the acronym “Hug-me” to describe the language spoken in Bombay streets, a mélange of Hindi, Urdu, Gujarati, Marathi, and English. In addition to those five “official” languages, there’s also the city’s unique slang, “Bambaiyya,” which nobody from anywhere else in India understands. In my novel Quichotte the title character tries to teach Bambaiyya to his son:

In Bambaiyya . . . rawas [was] “fantastic,” and raapchick, “hot” . . . baap . . . literally meant “father,” but in Bambaiyya it meant “great,” “best of the best” . . . majboot [was] literally “strong,” but [was] used to mean “fabulous,” “amazing,” “terrific.” . . . A sexy girl was maal, literally “the goods.” A girlfriend was fanti. A young, hot, but unfortunately married woman was a chicken tikka. . . . Bambaiyya was not a polite vernacular. It possessed the harshness of life on the city streets. A man you didn’t like might be chimaat, “weird looking,” or a khajvua, a guy who scratches his balls. . . . a gun was a ghoda, which meant “horse,” and a bullet was a tablet, or sometimes a capsule. So English, in such mutations, found its way into Bambaiyya too.

Clearly, any novel aiming for readability could not be written in “Hug-me” or Bambaiyya. A novel must know what language it’s being written in. However, writing in classical English felt wrong, like a misrepresentation of the rich linguistic environment of the book’s setting. In the end I took my cue from Jewish American writers like Philip Roth, who sprinkled their English with untranslated Yiddish words. If they could do it, so could I. The important thing was to make the approximate meaning of the word clear from the context. If Roth talks about getting a zetz in the kishkes, we may not exactly know what he means, but we understand from context that a zetz is some sort of violent blow and kishkes are a sensitive part of the human body. So if Saleem mentions a rutputty motor-car, it should be clear that the car in question is a ramshackle, near-derelict old wreck.

In the end I used fewer non-English words than I originally intended. Sentence structure, the flow and rhythm of the language, ended up being more useful, I thought, in my quest to write in an English that wasn’t owned by the English. The flexibility of the English language has allowed it to become naturalized in many different countries, and Indian English is its own thing by now, just as Irish English is, or West Indian English, or Australian English, or the many variations of American English. I set out to write an Indian English novel. Since then, the literature of the English language has expanded to include many more such projects: I’m thinking of Edwidge Danticat’s Creole-inflected English in Breath, Eyes, Memory, for example, or Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s use of Igbo words and idioms in Purple Hibiscus and Half of a Yellow Sun, or Junot Díaz’s slangy, musical, Dominican remake of the language in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.

History is the fluid, mutable, metamorphic consequence of our choices, and so the responsibility for it, even the moral responsibility, is ours.

I found myself in conversation, so to speak, with a great forerunner, E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India. I had admired this novel even before I had the great good fortune, as an undergraduate at King’s College, Cambridge, to meet Morgan Forster himself, who was in residence there as an Honorary Fellow, and was generously and kindly encouraging when I shyly admitted that I wanted to write. But as I began to write my “India book”—for a while I didn’t even know what it was called—I understood that Forsterian English, so cool, so precise, would not do for me. It would not do, I thought, for India. India is not cool. India is hot. It’s hot and noisy and odorous and crowded and excessive. How could I represent that on the page, I asked myself. What would a hot, noisy, odorous, crowded, excessive English sound like? How would it read? The novel I wrote was my best effort to answer that question.

The question of crowdedness needed a formal answer as well as a linguistic one. Multitude is the most obvious fact about the subcontinent. Everywhere you go, there’s a throng of humanity. Even in remote rural areas, the landscape is never empty. The human figure is always present. How could a novel embrace the idea of such multitude? My answer was to tell a crowd of stories, deliberately to overcrowd the narrative, so that “my” story, the main thrust of the novel, would need to push its way, so to speak, through a crowd of other stories. There are small, secondary characters and peripheral incidents in the book that could be expanded into longer narratives of their own. This kind of deliberate “wasting” of material was intentional. This was my hubbub, my maelstrom, my crowd.

When I started writing, the family at the heart of the novel was much more like my family than it is now. However, the characters felt oddly lifeless and inert. So I started making them unlike the people on whom they were modeled, and at once they began to come to life. For example, my maternal grandfather was a German-trained family doctor like “Aadam Aziz,” but as far as I know he wasn’t very involved in the politics of the independence movement, and it was when I allowed Aadam Aziz to become political that I understood who he was.

Also: I did have an uncle who was involved in writing for the movies, and his wife was an actress, but apart from those facts they were entirely unlike “Hanif Aziz” and “Aunty Pia,” whose stories went down entirely fictional paths. And I did have an aunt who married a Pakistani general, who, in real life, was one of the founders, and the first chief, of the much-feared ISI, the Inter-Services Intelligence agency. But as far as I know he was not involved in planning or executing a military coup, with or without the help of pepperpots. So that story was fiction. At least I think it was.

As I have mentioned, Saleem Sinai went to my school. He also lived, in Bombay, in my childhood home, in my old neighborhood, and is just eight weeks younger than me. His childhood friends are composites of children I knew when I was young. Once, after a reading in Bombay, a man came up to me and said, “Hello, Salman. I’m Hairoil.” He wasn’t wrong. The character of “Hairoil Sabarmati,” or at least Hairoil’s neatly oiled and parted hair, had indeed been based on him. But he had never been nicknamed “Hairoil” in real life. That was something I made up for the novel. I couldn’t help thinking how strange it was that my childhood friend introduced himself to me by a fictional name. Especially as he had lost all his hair.

But in spite of these echoes, Saleem and I are unalike. For one thing, our lives took very different directions. Mine led me abroad to England and eventually to America. But Saleem never leaves the subcontinent. His life is contained within, and defined by, the borders of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Also, in case there’s any doubt, I was not swapped at birth with another baby. (After the novel was published, a story ran in the sports pages of the Indian press about the country’s legendary cricket captain Sunil Gavaskar. Apparently, as a baby in hospital, he had actually been given to the wrong mother by mistake. Fortunately the mistake was discovered and corrected. I hadn’t expected Midnight’s Children to be discussed on the sports pages, but thanks to the Gavaskar story, it was.)

As a final proof that my character and I are not one and the same, I offer another anecdote. When I was in Delhi to do one of the first Indian readings from Midnight’s Children, I heard a woman’s voice cry loudly as I walked out onto the stage, “Oh! But he’s got a perfectly ordinary nose!”

Forty years is a long time. I have to say that India is no longer the country of this novel. When I wrote Midnight’s Children I had in mind an arc of history moving from the hope—the bloodied hope, but still the hope—of independence to the betrayal of that hope in the so-called Emergency, followed by the birth of a new hope. India today, to someone of my mind, has entered an even darker phase than the Emergency years. The horrifying escalation of assaults on women, the increasingly authoritarian character of the state, the unjustifiable arrests of people who dare to stand against that authoritarianism, the religious fanaticism, the rewriting of history to fit the narrative of those who want to transform India into a Hindu-nationalist, majoritarian state, and the popularity of the regime in spite of it all, or, worse, perhaps because of it all—these things encourage a kind of despair. When I wrote this book I could associate big-nosed Saleem with the elephant-trunked god Ganesh, the patron deity of literature among other things, and that felt perfectly easy and natural even though Saleem was not a Hindu. All of India belonged to all of us, or so I deeply believed. And still believe, even though the rise of a brutal sectarianism believes otherwise. But I find hope in the determination of India’s women and college students to resist that sectarianism, to reclaim the old, secular India and dismiss the darkness. I wish them well. But right now, in India, it’s midnight again.

–New York, November 2020

_____________________________________________

From Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie, introduction copyright © 2021 by Salman Rushdie. Used by permission of Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Salman Rushdie

Salman Rushdie is the author of several novels, including Grimus, Midnight's Children, and The Satanic Verses. He has written collections of short stories, including East, West, and co-edited with Elizabeth West a collection of Indian literature in English, Mirrorwork. He has also published several works of nonfiction, among them The Jaguar Smile, Imaginary Homelands, and Joseph Anton, a memoir of his life under the fatwa issued after the publication of The Satanic Verses.