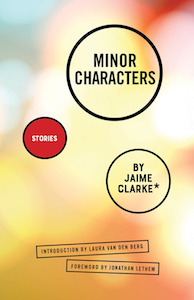

Jonathan Lethem on the Rich Lives of Jaime Clarke’s Minor Literary Characters

“He has done more, even, than Vonnegut in setting

his characters free.”

Where did it start, for you? Maybe it was when J. D. Salinger’s fiction revealed the intertwining of the fates of the siblings of Holden Caulfield, from The Catcher in the Rye, and that of the Glass family from Seymour: An Introduction and others of his fictions (if I recall correctly, Holden’s brother, killed in World War II, was earlier a contestant on the same juvenile game show as Seymour Glass).

Maybe it was when Kurt Vonnegut wandered into Breakfast of Champions, a book that was a compendium of characters both minor and major from his earlier novels, including Vonnegut’s fictional neglected science fiction author Kilgore Trout. Trout was an obvious transposition of the real neglected science fiction author Theodore Sturgeon, whose unlikely name was nevertheless authentic, and who’d been a friendly acquaintance of Vonnegut’s several years before. Bizarrely and wonderfully, Kilgore Trout was also credited with authorship of a mysterious satirical science fiction novel that appeared in 1975, two years after Breakfast of Champions, a book called Venus on the Half-Shell, which turned out to be written by another science fiction writer named Philip José Farmer.

Or maybe this kind of thing reminds you of Borges, who wrote stories featuring characters who’d wandered in from other authors’ writings (for instance, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver, from the travels, appears to have narrated “Brodie’s Report”). Or perhaps you were a partisan of Balzac’s La comédie humaine, a tapestry in which many minor characters recur and intertwine—major in one piece, minor in another. Maybe you think of Cervantes, whose Quixote, in the second volume of that massive novel, has to contend with rival fictions featuring himself, which he judges as bogus—noncanonical fanfic, in the present parlance.

For Jaime Clarke, it may well have begun with Bret Easton Ellis, Clarke’s literary idol and confessed “obsession.” Ellis revives characters from his first two novels, Less Than Zero and The Rules of Attraction, continually through his subsequent works, including the Bateman brothers, the elder of whom becomes Ellis’s Holden Caulfield (i.e., his most famous character, American Psycho’s Patrick Bateman). Later, in Lunar Park, Ellis plays the Vonnegut trick, wandering into his own fictional labyrinth, rendering himself a fictional character before anyone else could do it for him. Of course, Clarke was warming up to do this by translating Ellis into Vernon Downs in Vernon Downs.

That, I suppose, is where I come in, since before I was an author who might be asked to write a foreword, I was a minor—at best!—character wandering through a scene in The Rules of Attraction.

Really, I barely appeared. It’s too humiliatingly paltry to go into in any detail, so I won’t. At the time of the book’s publication I was, like Jaime Clarke, a bookseller, though not, like Jaime Clarke, a bookstore owner. I was a retail clerk, writing fiction at night, dreaming of glory.

In fact, I was a lot more like a Jaime Clarke character than a Bret Easton Ellis one; I’d only gotten to go to that rich-kids’ college by a weird act of willful imposture (but then again, hey, that’s a fairly good idea for a character—and eventually I’d write that character, Dylan Ebdus in The Fortress of Solitude).

There’s a superb lineage of such intertextual gamesmanship, in other words, yet I think here Jaime, in his characteristically generous manner, which I might be tempted to call self-effacing solipsism, has raised it to a giddy new level. I don’t mind saying I identify with the project on every level. There are certain bullying distortions that both consciousness (which places you-you-always-YOU! as the first-person shooter, the spider crouched in every web), and fiction (which relentlessly delegates characters into the rigid fates of Major and Minor), and authorship (which tends to claim a nonporous boundary: I Alone Made This Book!) impose, and which it has been my wish to see dissolved.

Here, Clarke has done more, even, than Vonnegut in setting his characters free: he’s flipped foreground and background, and at the same time invited others in (as one might open the doors of a bookstore) to browse, and revise, and interfere with, and extend, his fictional Who’s Who. The results strike me as a kind of party, even if I want to quibble with Clarke’s insistence that it is a going-away party (some of the best of which, in my experience, have involved people who did not subsequently go away).

In fact, I was a lot more like a Jaime Clarke character than a Bret Easton Ellis one.Here are both strangers and folks I know, from Clarke’s books, and as the authors of their own. Some are old friends—hey, Lauren Mechling, it’s been way too long!—and some are new acquaintances. Some I don’t really want to hang out with, but at a big enough party you can get a kind of thrill from briefly sharing the space with creeps. And, it is worth mentioning, some of Clarke’s own most winning fiction is here.

I’m a big fan, for instance, of the exchange of memos between Clarke and the film producers at Little Girl Bay Productions and 808 Films concerning their aborted adaptation of Clarke’s first novel. A perfect mise en abyme of the Hollywood tendency to put matters of derivativeness, originality, influence, and resemblance into a blender and throw money at it—only, usually not quite enough money.

The story reminds me of another one, by my old friend Carter Scholz, called “The Nine Billion Names of God,” the title of which is the title of another short story, by Arthur C. Clarke, an appropriation that, within the story, the “author” character Scholz defends to his skeptical editor by citing Borges’s use of Cervantes in his story “Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote.” Another great hall of mirrors. You can look all this up.

So, what am I doing here? In an introduction to one of his collections of short stories, Bruce Jay Friedman explains that the only way he could get started writing the introduction was to imagine that he was writing a short story about an author trying to introduce a collection of short stories. I’m trying to write myself into a fictional character, then: imagine this poor fool, Jaime Clarke’s sole friend whom he didn’t ask to write a story about a minor character in his fiction! Now, that would be a minor character indeed.

I wasn’t on the guest list, Jaime, but I crashed the party.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Minor Characters: Stories. Used with the permission of the publisher, Roundabout Press. Copyright © 2021 by Jaime Clarke.