Before the War: The Lost Delicacies of Aleppo

On the Wonderful Food of Syria

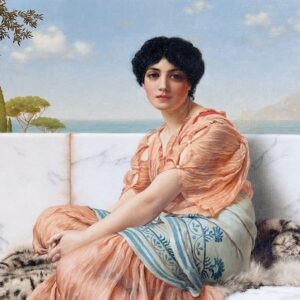

The white-gloved butler approached the dining table bearing an oval dish where the tiniest kibbeh balls had been nestled. Kibbeh is Syria’s national dish, a highly seasoned mixture of minced lamb and bulgur wheat that comes in myriad shapes and forms—round or oval balls that are usually fried, grilled or simmered in a variety of sauces; kibbeh can also be baked into a pie, or made vegetarian, with pumpkin, potatoes or simply flour instead of meat. And it can be made with rice.

I thought I knew most of the variations, but I had never seen such dainty kibbeh balls, nor had I seen that shape, which our hostess described as kibbeh qubab (meaning domes in Arabic because the balls were pinched at the top in pointed domes).

Kibbeh/ photo by Ben Stechschulte

Kibbeh/ photo by Ben Stechschulte

I was lunching that day with Lena Toutounji, in her beautiful Belle Epoque villa in the heart of “modern” Aleppo–much of the city centre and its souks are medieval while the “modern” part was built in the 19th and early 20th century. I had been eagerly anticipating the meal because of Lena’s reputation as one of the city’s finest hostesses, serving exquisite Aleppine dishes. From the look of that first course, I was in for a treat.

I helped myself to a few kibbeh balls and noticed they were reddish rather than brown which was unusual. As I picked up one to bite into, Lena suggested I eat it in one bite if I wanted my white shirt to remain pristine. The balls had been stuffed with minced lamb tail-fat seasoned with Aleppo pepper, hence the red color, and had I bitten into one the way I was about to, the melting fat would have spurted out onto my shirt and possibly that of my neighbor.

Even though this was many years ago, long before the Syrian uprising, I can still recall the luxurious feel of the hot melting fat bursting out of the crisp shell onto my tongue. Lena followed the kibbeh with a gratin of desert truffles (not as flavourful as European truffles but highly prized because of their short season, and the fact they are found wild in desert areas). The dish was more of a personal creation rather than a typical Aleppine one but her cook had managed to clean the truffles of every grain of sand, no easy feat. To finish, we went back to tradition with a typical Arab sweet, osmalliyeh, a sweet pie made by sandwiching clotted cream in between two layers of crisp “hair” pastry.

In those days, Aleppo was the ultimate destination for anyone visiting Syria, not only because of its historic monuments and medieval souks, the most enchanting of the Middle East, but also for its unrivaled culinary heritage, having earned the title of culinary capital of the Middle East from as far back as the 11th century. The city’s supremely sophisticated cuisine is quite distinct from that of Damascus, the capital, having being influenced by a succession of occupiers as well as refugee communities such as Armenians who had fled there from neighbouring Turkey at the beginning of the 20th century. One of the most delightful aspects of Aleppine cooking is the subtle combination of sweet and savoury flavours in dishes where meat is cooked with fruit and/or fruit juice—kibbeh sfarjaliyeh being an exquisite example where kibbeh balls are cooked with quince in fresh pomegranate juice; and kabab karaz or cherry kababs, the quintessential Aleppine dish where tiny meat balls are simmered in stewed sour cherries.

The city is sadly famous now for the wanton destruction wreaked on it by the fighting between the Free Syrian Army and a vengeful, uncompromising government.

Thankfully, I visited Aleppo often before it was destroyed, although it wasn’t until I met Lena’s brother, Pierre Antaki—who with George Husni, had founded the Académie de la Gastronomie Syrienne—that I was finally able to delve deeper into the secrets of Aleppine cuisine, thanks to them inviting me into their homes and those of their family and friends (not to mention the many dinners they organized for me at the Club d’Alep, a private members club famed for its fine Aleppine fare).

Until then, I had eaten mostly in restaurants or on the street. Not that these did not provide exciting culinary moments. One memory that often comes back whenever I watch the tragic news of the civil war is of an extraordinary old street food vendor in the now destroyed Souk al-Attarine (meaning souk of perfumers but in fact where you could also buy spices and enjoy typical Aleppine street food). The vendor spent his days making nothing but omelet sandwiches in a tiny stall halfway up the souk and he was surprisingly agile for his age. His routine was always the same. He beat the eggs for each omelet, working at mesmerising speed. Then, he added the seasonings, a little chopped parsley and spring onion before pouring the mixture into very hot oil. The egg mixture puffed up as soon as it spread in the oil. As the bubbles formed, the old man pressed on them with his spoon. The omelet cooked in seconds and as he lifted it out, he tilted it over the pan to let it drain the excess oil before laying it on pita bread and sprinkling it with a little more parsley and onion, then rolling the bread around it. As much as I loved him and the idea of his herb omelette, I could never bring myself to sample it. His stall was filthy, his clothes too as were the cracked bowls in which he beat the eggs, all of which were enough to keep my adventurous culinary spirit in check.

Levant stall in the souk in Aleppo.

Levant stall in the souk in Aleppo.

Nonetheless, however exciting street food is, and however much one learns from watching the vendors prepare their specialties, the only way to uncover the city’s culinary culture was to eat in people’s homes. Home cooks are the star chefs in Aleppo, far more than any restaurant chef could ever be.

Fortunately, Lena and Pierre had me over to many more memorable meals after that first exquisite one, George too, as well as several of their friends. My favorite Aleppine cook after Lena was Joumana Kayali, who unlike Lena, a gentle scion of an old Aleppine family, was a flamboyant fashion designer who lived in a newly built house furnished in reproduction Louis XV style in an affluent Aleppo suburb. But when it came to food, Joumana was as traditional as Lena—although as a Muslim her cooking was quite different from Lena’s, a Christian; there is a distinct difference between the cooking of each religious group.

At one meal, Joumana introduced me to another version of kibbeh I was unfamiliar with, kibbeh summaqiyeh which derives its name from the sumac sauce in which the kibbeh balls are simmered. The sauce is made with tomatoes and sumac water (made by soaking dried lemony sumac berries in water until the water becomes tart), and is a perfect balance of tart, sweet and spicy.

Joumana’s cooking was spicier than Lena’s and every year, when desert truffles are in season, I wish I had taken her recipe for her spectacular seven-spice lamb and desert truffle stew, which she served with a delectable cardamom and pistachio rice.

Another of my Aleppine discoveries that has now become very common in the West was at Maria Gaspard Samra’s, a home cook turned chef at the wonderful Mansouria Hotel who provided the recipes for the wonderful Les Secrets d’Alep by Florence Ollivry, was a beetroot mutabbal (basically the same as baba ghannouge but made with beetroot instead of eggplant).

A recipe for Anissa’s Beetroot Dip (Mutabbal Shamandar) can be found here.

Sweets are not usually served at the end of a meal unless it is a celebratory one or prepared for special guests; and when served at home, they are almost always store bought, being the reserve of specialist sweet-makers who tightly guard their recipes. I tried to sweet-talk the owners of Semiramis/Rose de Damas in Damascus, possibly the finest Arab sweet-makers anywhere, into letting me into their kitchen but they resolutely kept their doors shut. Luckily, Majed Krayem and Bassam Mawaldi, sweet-makers extraordinaire at Pistache d’Alep in Aleppo before the uprising—they have now relocated to Gaziantep in south eastern Turkey—were much more open and they immediately invited me into their kitchen. It was like the holygrail. So many sweets that I adored from when I was a child were all being made right before me, from the ‘hair’ pastry for k’nafeh and borma, to ghazl el-banat (meaning flirting with the girls in Arabic and basically the same as barbe a papa or candy floss) which I was very amused to see being started out with the same soft caramel that I, and most other Arab women for that matter, used to remove the hair on our legs. The caramel is called sukkar banat (meaning sugar of girls) and my mother and aunt used to make it for us when we were young and I always pretended I wanted to help stretch the caramel to cool in order to pinch some to eat like a candy. The sweet-makers stretched it exactly the same way although they worked with far greater quantities.

It is unlikely I will be going back to Aleppo any time soon but when I do, I wonder how many of the city’s culinary traditions I will find left. So many people gone, either dead or having fled the devastation to safer places. Though Lena is still there, safe in the zone controlled by the regime, and her cook is probably still with her although I am not sure who she will be preparing kibbeh qubab or other delightful party dishes for.

Anissa Helou

Anissa Helou is a writer, journalist, and broadcaster, born and raised in Beirut, Lebanon. Lebanese Cuisine, her first book, was nominated for the prestigious Andre Simon Award and was named one of the best cookbooks of 1998 by the Los Angeles Times. Mediterranean Street Food was described by the New York Times as "a marvelous book." It won the Gourmand World Cookbook Award 2002 as the best Mediterranean cuisine book in English. Helou lives in London, where she has her own cooking school, Anissa's School. An accomplished photographer and intrepid traveler, Helou is fluent in French and Arabic as well as English.