Badass Women of Polish Mythology

Investigating the rusalka and the weight of cultural baggage

The stories we tell have a way of coming back around to us. Fairytales, myths, urban legends–they’re more than just entertainment, they’re cultural heritage, and if we aren’t careful, they can end up changing the direction of our lives.

As a child, I fed on these tales, the scarier the better. Tell me about Baba Yaga, I would say. Tell me about her feet like chicken legs. If I ran out of properly horrifying mythology, I’d ask my grandmother to tell me stories from her own life. Tell me about the boy who died in the tsunami. It’s no wonder that I grew up to be a writer, and one obsessed with fairytales–and probably no coincidence that I also draw comics. Sometimes, when I’m flipping through my stacks of books and magazines, an old letter will fall out: a narrative poem from that same grandmother, illustrated with matryoshka dolls and snowmen and beaches.

These days, I’m particularly interested in what I call the Badass Women of Polish Mythology. These are women who guard hellhounds to keep them from pulling apart the universe; women who protect the dead, or give their lives to protect the realms of the living. I first met these women while sitting at my grandmother’s table, and they followed me around through every book that I read, eventually leaking into the first book that I would write: my novel The Daughters is focused not only on the Poland of my heritage but on the frightening ladies that populate that country’s legends. You see what I mean when I say that stories can change your life?

The potency of myth is more than that, though: not everyone who falls asleep listening to folktales ends up a novelist (or an woodsman, or a succubus). Certain stories stick to cultures for a larger reason. For example, it’s hard not to see a shared nervousness about women in the number of witches and hags and lost girls that populate our fairytales. And it goes both ways: when we cuddle up against these tales as children, they become a part of the narrative of our lives. Not just in our memory bank of bedtime frights but in our sense, too, of who we are and can be. Our once and future identities.

A story is a way of making something comprehensible when, without the story, it would be too large for our minds to wrap around. So we try to trap the things we’re afraid of inside these narratives, hoping to defang them. Only I have this theory: it doesn’t work like that. Add a listener to a story and you’ve got an echo chamber–listener and story shout back and forth to one another, getting louder and louder, larger and larger. Put a monster in there and it doesn’t disappear, it changes shape and becomes more frightening.

A story is a way of making something comprehensible when, without the story, it would be too large for our minds to wrap around. So we try to trap the things we’re afraid of inside these narratives, hoping to defang them. Only I have this theory: it doesn’t work like that. Add a listener to a story and you’ve got an echo chamber–listener and story shout back and forth to one another, getting louder and louder, larger and larger. Put a monster in there and it doesn’t disappear, it changes shape and becomes more frightening.

This is exactly why I like stories, actually. One of my favorite Badass Women of Polish Mythology is the rusalka, a water demon and spiritual vampire who shows up in different variations all throughout Slavic literature, and even inspired an opera by Antonín Dvořák. I’ve been illustrating a lot of Badass Women lately, and I saved the rusalka for last, because she is, to me, the most mystical and the most tragic.

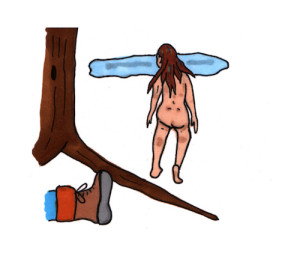

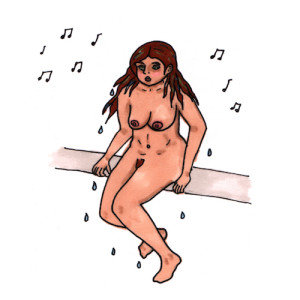

One of my favorite Badass Women of Polish Mythology is the rusalka, a water demon and spiritual vampire who shows up in different variations all throughout Slavic literature, and even inspired an opera by Antonín Dvořák. I’ve been illustrating a lot of Badass Women lately, and I saved the rusalka for last, because she is, to me, the most mystical and the most tragic. The rusalka is a water spirit who climbs out of her river or lake or stream and into a tree, singing a song to lure men to her in the forest. Some versions of the story have it that she can’t ever leave the water entirely, and must leave a foot dangling, or a lock of her long and tangled hair. She is always naked and beautiful, asking men to come feed her so she can take their souls. Which they do–poor saps, they’re often glad to. Sometimes she’s the remnant of a drowned girl, seeking vengeance: a riff on the Hungry Ghosts of Japan, but looking only for bread and salt. (And, well, the life-force of strapping young men.) In Dvořák’s version (or anyway, in the libretto written by the Czech poet Jaroslav Kvapil) the rusalka is an immortal who falls in love with a human man and ends up sacrificing herself for him despite the fact that he betrays her. It’s basically The Little Mermaid but with a desperately unhappy ending: she even sells her voice to a witch. And although the man dies too, the rusalka sends his soul to heaven, while she, for her trouble, ends up as a wraith.

The rusalka is a water spirit who climbs out of her river or lake or stream and into a tree, singing a song to lure men to her in the forest. Some versions of the story have it that she can’t ever leave the water entirely, and must leave a foot dangling, or a lock of her long and tangled hair. She is always naked and beautiful, asking men to come feed her so she can take their souls. Which they do–poor saps, they’re often glad to. Sometimes she’s the remnant of a drowned girl, seeking vengeance: a riff on the Hungry Ghosts of Japan, but looking only for bread and salt. (And, well, the life-force of strapping young men.) In Dvořák’s version (or anyway, in the libretto written by the Czech poet Jaroslav Kvapil) the rusalka is an immortal who falls in love with a human man and ends up sacrificing herself for him despite the fact that he betrays her. It’s basically The Little Mermaid but with a desperately unhappy ending: she even sells her voice to a witch. And although the man dies too, the rusalka sends his soul to heaven, while she, for her trouble, ends up as a wraith.

Here’s the great thing about myths, though: they change every time you tell them. Although they get louder and louder, they also get distorted, with little pieces falling off when they don’t interest a particular storyteller, or tiny elements growing to outrageous sizes when they do. Which means Dvořák’s rusalka doesn’t have to be mine, and neither does any version where she’s mindless, meat-eating. My rusalka is sad, but she’s also smart. She takes what she needs without being insulted that the world calls her a demon for it. Maybe she loves some of the men that she kills. Maybe she doesn’t. Still she goes on. What does that say about me? I’m not sure.

Here’s the great thing about myths, though: they change every time you tell them. Although they get louder and louder, they also get distorted, with little pieces falling off when they don’t interest a particular storyteller, or tiny elements growing to outrageous sizes when they do. Which means Dvořák’s rusalka doesn’t have to be mine, and neither does any version where she’s mindless, meat-eating. My rusalka is sad, but she’s also smart. She takes what she needs without being insulted that the world calls her a demon for it. Maybe she loves some of the men that she kills. Maybe she doesn’t. Still she goes on. What does that say about me? I’m not sure.

You give a story shape. A story gives you shape. It’s a fair trade – almost scientific, in fact. Equal and opposite forces. And although I’ve said that the number of witches in fairytales gives me pause, it’s also something of a relief in the face of the women as represented in ordinary media. Fairytales are extraordinary media, and though they put women (or, to be fair, people) in boxes as surely as the phrase Mommy Blogger or Who Wore It Best? they also remember the reasons that someone thought those boxes were necessary, to keep us orderly. They remember the pathos, the power, the blood of humanity. Our disorderly natures, kept just out of view. Until, that is, we pull ourselves out of the water and find we need them.

You give a story shape. A story gives you shape. It’s a fair trade – almost scientific, in fact. Equal and opposite forces. And although I’ve said that the number of witches in fairytales gives me pause, it’s also something of a relief in the face of the women as represented in ordinary media. Fairytales are extraordinary media, and though they put women (or, to be fair, people) in boxes as surely as the phrase Mommy Blogger or Who Wore It Best? they also remember the reasons that someone thought those boxes were necessary, to keep us orderly. They remember the pathos, the power, the blood of humanity. Our disorderly natures, kept just out of view. Until, that is, we pull ourselves out of the water and find we need them.