Autumn Has Always Been Poets' Season

Nietzsche, Emerson, and the Eternal Return of the Falling Leaves

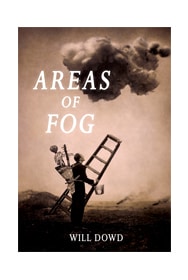

The following are entries from Will Dowd’s weather journal written over the course of one year.

On Happiness

(June)

All winter, you looked forward to summer. You anticipated the return of the sun with religious fervor, convinced that ecstasy and sunlight are the selfsame. But here you are, barefoot on a green lawn in June, realizing the difficult truth that happiness is not, in fact, photosynthetic.

My people, the Irish, have always been skeptical of happiness. Swift considered it a self-deception; Shaw doubted anyone could bear it for long (“A lifetime of happiness . . . would be hell on earth”); and Joyce, in over 2,000 pages, hardly mentioned it.

Perhaps the island’s chronic cloud cover is to blame. It would explain Samuel Beckett’s definition of happiness, perhaps the saddest ever penned: “We spend our life . . . trying to bring together in the same instant a ray of sunshine and a free bench.”

In America, you can find no shade from the publicity surrounding the abstract concept of happiness.

Happiness is wanting what you have.

Happiness is learning to dance in the rain.

The aphorisms are everywhere. They descend on you like inchworms.

We’re especially plagued at the moment. It’s commencement season, when robed elders indulge in a bit of self-mythologizing under the guise of advising the next generation. The theme is always the same—the secret equation of happiness—and the takeaway is always an empty paradox. This year, MIT graduates were instructed, or rather commanded, to “Solve the unsolvable!”

It makes me think of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who delivered the commencement address at the Harvard Divinity School in 1838.

(I was recently inside the Divinity Hall Chapel. It’s surprisingly small, and it contains the most unforgiving variety of wooden pew I’ve ever encountered.)

Emerson’s speech began well enough: “In this refulgent summer, it has been a luxury to draw the breath of life,” he said. “The grass grows, the buds burst, the meadow is spotted with fire and gold in the tint of flowers.”

But once he’d covered the weather, Emerson turned his attention to the more controversial topic of incompetent preachers and the decaying church.

He also divulged his secret equation for happiness: go alone. Don’t listen to the bromides, the banalities, the “penny-wisdom.” You don’t need them. “All men have sublime thoughts,” he said. Look inward.

Many Boston clergy regarded the speech as an “incoherent rhapsody” and Emerson himself as “a sort of mad dog.” Even his aunt thought he was possibly under the influence of some malevolent demon. He was barred from formal Harvard functions for over 30 years.

It was a blow. Denunciation on such a scale always is, even for an evangelist of self-reliance.

But that October, Emerson’s “sunk spirits” suddenly recovered. “[H]ow quick the little wounds of fortune skin over & are forgotten,” he wrote in his journal.

He attributed his miraculous change in mood to the cold, crisp air of the autumn nights.

Who doesn’t love an autumn night? Aren’t we all just counting the days to October, to the wool sweaters and the burning leaves, to when we’ll be happy?

The First Draft of an Early Fall

(October)

It was a blurry week of rain and mist and moths. Of red leaves strewn like tickets to a rained-out concert. Seven palindromic days of sogginess and lethargy when all one could do was stare out a rain-streaked window and write rhyming couplets in the condensation.

Autumn has always been poets’ weather.

There’s at least one famous poet who admits she can only write in the fall, when a certain gnawing chill enters her knuckles. (This same poet once told me that her cat, William, writes most of her best poems.)

Among the Romantics, you weren’t cool unless you had at least a quatrain on the wanton grandeur of the season. Keats had his “season of mists,” Byron his “mellow autumn,” Wordsworth his “pensive beauty,” and Clare his “fitful gusts.”

While they were all swimming in Shakespeare’s inkwell, only the pastoral poet John Clare went so far as to claim authorship of Shakespeare’s work.

“I’m John Clare now,” he told an editor who visited him in Northampton General Lunatic Asylum. “I was Byron and Shakespeare formerly. At different times, you know, I’m different people—that is, the same person with different names.”

While Clare’s doctor blamed his madness on “years of poetical prosing,” Clare himself blamed the autumn, a season that never failed to swaddle him in a “stupor of chilling indisposition.”

It’s an old idea—a Greek idea—that souls travel, that they pass through terrestrial, aquatic and winged forms, that in due course some of them sit upright and hold a quill, that among these are a few poets who return century after century to defy the right margin.

I don’t believe in literary reincarnation, of course.

So what if the definitive dissertation on metempsychosis in English romantic poetry was written in the late 1940s by one Wilfred Dowden?

Still, the idea was on my mind this week when I met my oldest friend’s newborn son. He was squirming in a mechanical swing, dressed in a sock, still scowling from his amphibious assault on the world. (No matter what ill-considered piercings or lizard sleeve tattoos we acquire over the years, we never outdo that first metamorphosis from water creature to land animal.)

It occurred to me that this child, born one week ago, has never seen the sun. For him, the rain has always been falling, the wind always howling. Just imagine the romantic poem he could write.

If only his hands weren’t mittened and he had the fine motor skills to grip a pen.

If only he had some words to work with rather than the wet leaves that stir and scatter in sudden gusts behind his eyes.

At one point, he opened his pursed mouth and I thought maybe, if he was Milton or Dante returned, some verse might emerge.

But it was just milk spittle.

It was definitely not poetry.

I suppose it might have been art. It’s hard to tell these days.

The Season of the Soul

(October)

I love to take long Sunday morning walks in October when the wind is crisp and the leaves are tumbling down and every 20 feet or so you have to step over the viscera of a shattered pumpkin.

This morning I was almost run over. I was distracted by a dozen crows screaming in an oak tree. It might have been a crow funeral (they do that).

Anyway, an ultramarine minivan blew through a stop sign (they do that) and missed my foot by a foot.

Afterward, I spent a long time fiddling with my iPod, trying to find a song for the occasion of not being flattened. I thought of Nietzsche, who preferred his music “cheerful and profound, like an October afternoon.”

Nietzsche had an autumn problem. For ten years he wandered Europe like a hypochondriac Goldilocks looking for a warm, but not humid, autumnal climate. He finally settled on Turin, whose impeccable grid of paved streets allowed him to take walks despite his failing eyesight.

“Wonderful clarity,” he wrote upon arriving in Turin, “autumn colors, an exquisite sense of well-being emanating from all things.”

Of course, it was on one of these morning walks that Nietzsche encountered a broken-down carthorse being whipped. He flung his arms around the animal, sobbed violently, and never regained his sanity.

I didn’t see anything this morning to make me lose my sanity. Just some roses on their deathbeds. Just the sun, low in the sky, sliding its meager warmth like a final offer face down across a table.

But I do keep thinking of that close call, and how my ancestors, every last forefather and foremother, survived without exception to bear children, and how those children in turn survived to bear children—an unbroken chain of human beings who never ate the wrong berry, who never missed the snake in the grass, who never misjudged the strength of a branch or their own strength in the waves, who were never the friend drowned in the creek but always the friend who ran home dripping to tell about it, who were never the mourned, always the mourning, forever, all the way back, pin balanced on pin, the ultimate winning streak, the inconceivable, astonishing luck of it.

Silver Aslant

(November)

This morning I planned to write about the smoldering festival of Samhain, when Celtic druids would light leggy bonfires on hilltops to stave off the growing darkness of winter, and then I planned to speculate on what bloody pagan rites we might enact to stave off the growing darkness of daylight saving time, a tradition (abolished in Russia this week with a flick of Putin’s pen) that I despise, not simply because the early twilight plays havoc with our circadian rhythms, but because the very concept represents a hubristic human meddling in the oceanic mystos of time.

I was going to write about all this, but then the rain turned to snow.

I saw it happen through the café window. The cold drizzle was suddenly full of white feathers.

It made me think of Howard Nemerov, who claimed that the difference between prose and poetry was the difference between rain and snow (one falls, one flies).

I’m not sure I agree with Nemerov.

Maybe poetry is just prose dropped from a loftier height, the words crystalizing on the way down. Or maybe it’s the other way around. I try not to brood too much over such things.

I don’t want to end up like Yury Nikitkin.

Yury Nikitkin was a 66-year-old Russian man who loved literature. On a snowy evening last January, he invited an old friend to his home. The two men began draining shots of vodka. Before long, they were in a heated argument over which literary genre was more important—poetry or prose. While Nikitkin contended that prose was the real literature, his guest insisted it was poetry. The guest settled the dispute by plunging a knife into Nikitkin’s chest, then fleeing to a nearby village (one falls, one flies).

The poetry lover was caught and, earlier this week, sentenced to eight years in a penal colony.

What I find most disturbing about this literary murder is the fact that Yury Nikitkin loved poetry too. He was well-known in his small town as an unemployed eccentric who would stop people in the snow-powdered streets to recite the verses he’d committed to memory.

If I were sitting in a dusky bar right now, I would down a shot of vodka in Yury Nikitkin’s memory.

But I’m in a café—and that’s probably for the best. When considering the relative merits of prose and poetry, one should stick to coffee.

__________________________________

From Areas of Fog. Used with permission of Etruscan Press. Copyright 2017 by Will Dowd.

Will Dowd

Will Dowd was born in born in Braintree, Massachusetts. He earned a BA from Boston College, as a Presidential Scholar; an MS from MIT, as a John Lyons Fellow; and an MFA in Creative Writing from New York University, as a Jacob K. Javits Fellow. His writing and art have appeared in numerous magazines. He lives in the Boston area.