Life, Death, and Art: On the Photography of Reva Brooks

“The minute I got the camera around my neck it was part of my body.”

By the time I met Reva Brooks, she had been dead for 15 years. I was perusing the locked case where San Miguel de Allende’s bilingual library houses its most precious books when my eye fell on a small square volume of astonishing photographic portraits.

Dead Child, circa 1955 © The Estate of Reva Brooks / courtesy Stephen Bulger Gallery

Dead Child, circa 1955 © The Estate of Reva Brooks / courtesy Stephen Bulger Gallery

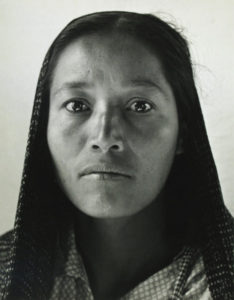

Women’s faces, staring blankly, awash in joy or grief, stunned by life. Little boys in a pool; one crawling through mud towards the camera. Then the photograph that stopped me cold: a child laid out on a bier of flowers, eyes open under a gold paper crown.

Reva Brooks had arrived in San Miguel de Allende in 1947 with her husband, the landscape painter Leonard Brooks. His one-year sabbatical from a Toronto teaching job turned into a 50-year self-exile from Canada. San Miguel has that effect on people, on me, even now.

The couple quickly became part of San Miguel’s nascent artist colony. Leonard was offered a teaching job at the Escuela Universitaria de Bellas Artes; its founder, Stirling Dickinson, invited them on sketching trips into the campo. While the men drew the desert, Reva talked to the locals, and with twin-lens Rolleicord Leonard had given her so she could document his paintings, she began photographing the people she met, waiting, as was her habit, for that “decisive moment” to take her shot.

“The minute I got the camera around my neck it was part of my body,” Reva said. She was, by her own admission, untechnical and unscientific, yet she taught herself to use the camera and the darkroom in order to get the images she wanted. “I loved seeing those faces come out in the developer.”

Confrontacion, circa 1955 © The Estate of Reva Brooks / courtesy Stephen Bulger Gallery

Confrontacion, circa 1955 © The Estate of Reva Brooks / courtesy Stephen Bulger Gallery

As John Virtue, author Leonard and Reva Brooks: Artists in Exile in San Miguel de Allende, tells it, one day, Reva answered a pounding on her door. She hurried to a neighbors’ house where a distraught woman begged her to take a portrait of her son. He’d fallen ill while she was at work, and by the time she returned, he had died, the fifth child she had lost. Reva looked down into the casket, into the dead, shiny eyes of the infant, insects buzzing across his face. “You must brush away the flies,” she told the mother. Using only the light from the sun, she took pictures of the child and those standing around the casket. In her darkroom, she isolated the mother, Elodia, producing a dark print of a woman ravaged yet undefeated by loss.

The Grandmother, circa 1955 © The Estate of Reva Brooks / courtesy Stephen Bulger Gallery

The Grandmother, circa 1955 © The Estate of Reva Brooks / courtesy Stephen Bulger Gallery

The portrait of Elodia was acquired by the New York Museum of Modern Art and published in The Family of Man exhibit in 1955, the most-viewed photography exhibit in history. 20 years later, the San Francisco Museum of Art selected Reva as one of the top 50 women photographers in the world and published her photograph “Dead Child” in Women of Photography: An Historical Survey. “The photographs are uncompromisingly honest,” the text read, “yet they are poetic.”

In the early 1960s when Reva and Leonard moved in Paris for a time, she was invited to exhibit in “Great Photographers of our Time” at the Salon International du Portrait Photographique at the Bibliotèque Nationale, alongside the work of Ansel Adams, Man Ray and Margaret Bourke-White. One critic wrote, “The most remarked about entry in the exhibition has certainly been that of Reva Brooks. . . sadness so close to despair has never been shown with such intensity.”

“I don’t go pursuing photographs,” Reva said. “When I see something that moves me, I just stand around until I can get it.” She waited, she said, two years to take a shot of an indigenous woman, Julieta, standing in a doorway, one of her most iconic portraits.

I discovered the book of Reva photographs just after I had finished my novel Refuge. It was Reva’s picture of the dead child that stopped me cold. In the novel, Cassandra MacCallum—a Canadian nurse who first takes up the camera in Mexico—is called upon by a neighbor to photograph her young daughter who has died. I stared at Reva’s photograph of the dead child: this was the picture I had imagined Cassandra taking.

Cass and Reva were both self-taught. Both focused on the human face. Both photographed dead babies at a time when Mexican families were making the transition from painted recuerdos to photographic portraits of their dead children.

It was affirming to discover a real-life character so like my fictional protagonist, but it was disturbing, too. I’ve spent the past seven winters in San Miguel de Allende. In the late 1990s, Reva had an exhibition in Kingston, Ontario, where I live in the summer. Had I heard about her and sublimated the information into Cassandra’s character? Was the experience of these two women—one real, one fictional—so common that what I wrote was, in fact, cliché? Or had I tapped into some female-photographer truth?

In her biography, Reva explains that she shortened the strap on her camera so it would always rest at the level of her heart. “You must hold the camera over your heart to feel connected to the subject,” she said.

If I had read that detail a year earlier, it would have found a place in the novel.

“Had I heard about her and sublimated the information into Cassandra’s character? Was the experience of these two women—one real, one fictional—so common that what I wrote was, in fact, cliché? Or had I tapped into some female-photographer truth?”

Both women grew up in the early decades of the last century. Neither one held her art above her life. If I had known Reva’s story, could I have resisted its sad drama? Instead, Cass lets go of her camera as she lets go of everything: accidentally, almost whimsically. Yet it is a photograph, one that makes its way to Burma from Canada and back again, that unravels a secret Cass has kept bound up for half a century.

For a time, I considered reproducing Cassandra’s photographs in the novel—in reality, a pastiche of the work of others that I kept taped to the wall above my writing desk. Had I known about Reva through the 14 years it took to write this novel, her photographs would have been on my wall, too. As it was, I only had time, during the final copy edit, to add her name to a list of women picture-takers.

Tina Modotti. Dorothea Lange. Annie Lebowitz. Diane Arbus with her dwarfs and jugglers and ugly people. Reva Brooks. Even Berenice Abbott. Eventually, every photographer leans in to snatch a face. Only a handful make it a habit. And of those, only a few get truly close. But even they aren’t willing to lean in all the way, to let go of story and see what’s left.

Reva’s last exhibition was in 1998 at the Stephen Bulger Gallery in Toronto. By another strange coincidence, 20 years later, I chose this photographic exhibition space for the launch of >Refuge. Stephen Bulger, who, it turns out, is the agent for Reva’s work, mounted a small exhibit to coincide with the launch. Surrounded by Reva’s portraits, I will read Cassandra’s story, uncertain in that moment whether art is imitating life, or the other way around.

Merilyn Simonds

Merilyn Simonds is the internationally published author of 18 books, including The Holding, a New York Times Book Review Editors' Choice and the Canadian classic nonfiction novel, The Convict Lover, a finalist for the Governor General's Award. In 2017, Bookmark Canada unveiled a plaque to honor the place of The Convict Lover in Canada’s literary landscape. Her most recent novel is Refuge, released in September by ECW Press. To read more by Merilyn Simonds, visit Books Unpacked.