Ruth Asawa’s journey took her from a life in black and white to a world of saturated color, with friends waiting for her on the other side.

Unlike the drab trains of the war years, the Southern Railway sported green cars with red and silver wheels. Its windows framed a verdant Southern countryside flying past. After winding through the Great Smoky Mountains, the train stopped near Asheville, at the village of Black Mountain, North Carolina. There, it deposited bags, parcels, and travelers, including the twenty-year-old novice from California by way of Arkansas and Milwaukee. Roiled by waves of excitement and insecurity, Ruth felt like a country bumpkin entering this fabled artists’ colony.

At the station, she spotted a familiar face, Elizabeth Schmitt, who drove her to campus past forests lush with fern and tulip magnolia, flanked by blue mountains. Just as Elaine’s letter had described, nature offered an open-air annex to the classroom and studio, where Ruth would gather leaves and flowers, twigs and bark for art projects. Approaching the Lake Eden campus, she saw spare buildings, grounds, and roads tended by work crews of faculty and students. The man clearing brush might deliver tomorrow’s lecture; the young woman driving trash to the dump might be a Paris-schooled painter. Framing the entrance were spare white boards arranged by Josef Albers himself.

Ruth had arrived in utopia. Black Mountain College was a new species of higher education: a liberal arts college that integrated the arts into every discipline. It encouraged experimentation over standard measures of success like regular exams, accreditation, and degree programs. Above all, students learned from working artists—a principle that would shape Ruth’s practice and life.

Black Mountain was founded in 1933 by two charismatic academic rebels: classics professor John Andrew Rice and physics instructor Theodore Dreier. The big bang that led to Black Mountain’s formation was Rice’s dismissal from Rollins College in Florida due to a series of faculty disputes over everything from the length of the academic day to the ethics of modern love and obscenity in art. The aftermath sparked the resignation of Dreier, an idealist from a wealthy family. Together with a handful of like-minded innovators, they found their site: the old, white-columned Blue Ridge Assembly of the Protestant Church near Black Mountain.

The school welcomed free-thinking artists and intellectuals, many fleeing fascist Europe and drawn by an offer of artistic freedom, room and board, plus modest spending cash. The founders and faculty worked to make art the central core—and not a peripheral frill—of a liberal arts education.

Black Mountain burned brightest in the years just following World War II. Chronically poor and consumed by chaos, it would flame out by 1957. But in the autumn of 1946, the college was just reaching its halcyon moment of creative exploration and egalitarianism. The goal was to prepare students for a life devoted to art and communal responsibility, not producing a commodity or making a fortune.

Josef Albers’ sayings resonated in her mind for life: “Let the material express itself.” “Don’t bring your ego with you.” “Heartbeat of paper.”Black Mountain was unaccredited. Faculty gave no regular tests and assigned letter grades only to establish transfer credits. Among Josef Albers’s many aphorisms and oracular sayings was “Art knows nothing of graduation.” Also missing from campus culture was football, although an annual students versus faculty scrimmage took place, mainly to poke fun at college gridiron madness elsewhere.

Students were given breathtaking freedom to experiment and create in their studios, and to make their voices heard on school issues and policy. There was no artificial separation between faculty and students in their lives outside class. They worked together, dined together, and held Saturday evening dances and concerts in each other’s company. They shared their ideas endlessly, sometimes exhaustingly. Airing their opinions, they asked Ruth’s opinions too. No one had ever done that before. Freedom reigned and raged. “The magnet of Black Mountain was not luxurious living, but luxurious minds,” one student put it. Everyone was assigned chores and shared sleeping quarters, but all had their own private study, an 8-by-8-foot cubicle in which to work. Ruth had never experienced such dizzying liberty, and she attacked her studio work and her farm chores with equal fervor.

That summer of 1946, when Ruth put down her suitcase in a long, narrow dormitory with beds for eight young women, she saw the student body included students of color. One of her first roommates was a Spelman College graduate named Mary Parks. This stunning Georgian, who resembled the actress Dorothy Dandridge, took to Ruth right away. Reared gently never to wear slacks, Parks had just bought her first pair of “dungarees” after learning that jeans and sandals were art school staples. At Saturday soirées, Ruth soon saw that young women danced in floor-length frocks, sewn from dyed flour sacks. Perhaps a farm girl could feel at ease here after all.

Then came a letdown: Ruth’s meeting with weaver Anni Albers didn’t go as expected. When Ruth tried to enroll in her class, the earnest, soulful-eyed Albers said she couldn’t possibly teach her to weave in just six weeks. Ruth would have to rethink her summer. At the weaver’s urging, she signed up for Color and Design with Albers’s husband, the painter Josef Albers. Amid Nazi pressure closing the Bauhaus and their mounting persecution of Jews, Albers fled Germany with Anni, who was of Jewish descent. He arrived in 1933, speaking little English, delivering his lectures in a distinctive Deutsch-flavored dialect, and punctuating sentences with “Ja?” His mission, he said, was “to open the eyes.”

Josef Albers’s first impression of Ruth during the Summer Institute was decidedly mixed. In a note to the Registrar’s Office on August 16, 1946, he wrote: “A very good soul. Talented but very unorderly. Told me that she decided to help her father on his farm he rented recently.”

Ruth didn’t make a fetish of tidiness. But Albers, whose studio was likened by some to “a monk’s cell in austerity,” refused to make his usual site visit to her studio until she got it organized. In her notebook, she would pencil notes in block capitals—“clean immediately”—and then, as directed, send a messenger to Albers as soon as the studio was spruced up and ready for his inspection.

Once Albers’s order was established in Ruth’s studio, their creative chemistry grew warmer. Albers brought Bauhaus values of functionality and beauty to Black Mountain. He exhibited humility toward materials and never threw anything away. In Germany, he had crafted stunning stained glass windows from green bottle shards and scrap metal, achieving an alchemy of craft and economy of means that Ruth admired.

Albers didn’t worship free expression. His constant refrain was that his students should pursue free expression on their own time; in his class, they were still students, not artists. Students who had trained in Paris or mounted shows of their art were crestfallen. Resentment simmered over his stern rule, especially among the budding abstract expressionists. But his core values—learning to see things anew, developing technique through eye-hand coordination, working with everyday objects—all resonated with Ruth.

Impatient with trends, Albers also mocked cults of personality in art as: “Picasso-itis,” “Klee-tomania,” and “Matisse-somnia.” He would scorn the coming wave of abstract expressionism as self-indulgent.

Albers’s classes didn’t feature conventional lectures. Rather, he presented a design problem for students to solve back in their studios. The next day they would bring their projects to class, spread them on the floor, and receive Albers’s comments along with those of their fellow students. In that way, they got a range of views, from their peers as well as their professor.

Design problems posed by Albers included balancing figure and background, giving equal attention to the form in positive space and the empty or negative space that surrounds and defines it. He also would assign drawings of curved planes or intersecting lines, asking the students to show which one is on top and “indicate the air between by making air, not by touching.” Writing one’s name backward in the air was assigned to sharpen the coordination of eye, hand, and brain. Exercises in mirror writing and mirror drawing flowed from that. Students also were challenged to draw a Coca-Cola or cigarette logo from memory. While some bristled, Ruth was entranced:

I signed up for Josef Albers Basic Design and color classes and another world opened up for me. I also studied drawing and painting. Our subject matter varied. On rainy days, we painted umbrellas and rain boots. When the first daffodils popped open, Albers came in with a huge bouquet of yellow daffodils, when a later student drove up in his jeep, we would have a lesson in concave, convex ellipses using the hub caps and wheels. His most frequent statement in class was, “Draw what you see, not what you know.” We drew a terracotta flower pot over and over again as a basic form. There were no advanced courses at BMC.

Albers’s mission to open the eyes included explorations of materials ranging from leaves to trash in exercises called “matière studies.” One of Albers’s signature lessons, matière studies asked students to focus on the visual qualities of a material that could look like something else—a trompe l’oeil to trick or, as he said in his accented English, “schwindle” the eye.

Paper could be pricked with a needle to look like terry cloth or crinkled to resemble leather. A layer of green mold could masquerade as velvet. Students raided the barnyard and butcher shop for materials.

Ruth observed that the texture of sun-dried cow manure resembled Ry-Krisp. Elaine Schmitt gamely fetched a glistening pile of cow intestines for her study. Mary Parks beat soapsuds into a white froth identical to egg whites. Albers, making rounds in class with his ruler in hand, stung her by saying that she didn’t look at it correctly. Schmitt wrote home that friends celebrated her birthday with a faux feast in which a stone posed as meat loaf, and crowned her as the class’s “matière momma.” But not all were so enthralled. Dissident students once turned Albers’s lesson on its head, submitting, as mock cow dung, the real thing. Very good, Albers said, until he got close and sniffed it, discovering he was the one who got “schwindled.”

Ruth liked Albers’s approach to drawing, especially his appreciation for positive and negative space. It invoked the principle of yin and yang from Taoist philosophy, which respects the balance of equal and opposite forces: male and female, light and shadow, day and night, life and death—each containing the seed of the other. Where others chafed, Ruth diligently absorbed lessons and performed exercises refining the coordination of brain, eye, and hand—recalling the discipline of her childhood calligraphy classes in Japanese school. She approached Albers’s classes with her eyes open, her brain awake, and her hands nimble. She filled pages with wavy lines called “meanders,” practiced lettering, and folded and unfolded paper, feeling the texture of the page to find the pulse of paper. Albers’s habit of never throwing anything away deeply satisfied her sense of the frugal. His sayings resonated in her mind for life:

“Let the material express itself.”

“Don’t bring your ego with you.”

“Heartbeat of paper.”

Albers’s views on the relativity and interaction of colors were fresh and daring—he argued that colors changed when placed side by side, like people who change in relation to each other. He respected the eloquence of a line and how it defines itself and the negative space around it. His focus on figure-ground relationships recognized the principle that the empty space in a design is as important a design element as the form or figure that is drawn or painted. His teachings recalled the precision of Ruth’s old sensei, who assigned endless practice in picking up and putting down the brush. In life drawing class, students drew a nude model without looking at the paper, directed to feel the flesh with their pencil. Albers’s devotion to developing motor memory made sense to Ruth.

Albers engaged Ruth with his ideas about the relativity of color, and the importance of both positive and negative space in a design. As Ruth would later recollect in an interview:

He was primarily interested in color and relativity of color . . . to show color is not fixed; its relative to what’s next to it. A color will change with its neighbor. And he always talked about the same thing—that people change, depending on who their neighbors are . . .

The other thing was that he related Taoism and the oriental philosophy very much with black and white, white and black. And showing that even black will change . . .

One of the problems that he gave in school, was never to see anything in isolation; that you can define space and you can define an object by defining the space around it.

She welcomed Albers’s discipline. Airing her feelings was alien to her upbringing and culture, so, she said, “I was a very obedient student.”

Not so with all Black Mountaineers. Some students, who came to develop their style, didn’t want to repeat basic color and design exercises. One who resisted Albers’s Teutonic rule was the young Robert Rauschenberg. A Navy veteran who had studied at Paris’s Académie Julian, Rauschenberg accompanied his friend Susan Weil to Black Mountain on the G.I. Bill. Frustrated by the rigors of design class, Rauschenberg found Albers a “beautiful teacher” and “an impossible person.” He would discover a more congenial milieu in the New York School, an informal group of abstract artists, poets, dancers, and musicians working in mid-century Manhattan.

“Discipline!” Albers would say. “Who likes not discipline, let him leave soddenly!” His critiques could be withering: “Don’t be proud of your work of 12 hours; I wait for your work of 12 weeks.” Ruth wrote it all down in her notebook, along with other Albers aphorisms:

Art is never wrong.

The purpose of art is to surprize!

His rare words of praise—delivered in German—included a murmur of “Schön, schön” (beautiful) or an exclamation of “Donnerwetter!” (thunderstorm), an idiomatic expression of surprise.

Albers taught three-hour classes, from nine to noon, twice a week. All students brought their solutions to design problems, submitting to his appraisal. It was a case of “show me what you’ve got, or else.” Those without work to show shouldn’t come to class. Assignments carried consequences; no one could hide or bluff. Students spread their work on the floor.

With quickening pulse, they awaited the element of theater that attended Albers’s arrival in class, immaculate in his white jacket, a cigarette jutting from his lip, a lock of steely hair over his blue eyes. They braced for his critique with mingled reverence and intimidation.

In life drawing class, Albers extolled the roundness of the female form, and the ripe curve of the hip or folds of the belly of a prone model, explaining the anatomical perspective that he wanted to his students to see and feel through their pencils. Ruth, in an interview decades later, recalled his public grasping of models:

When he taught drawing, he wanted you to look at the figure. He didn’t care whether you did long, willowy figures. You know, he wanted you to see that one form was in front of the other if the model was lying. He’d want you to see the foreshortening. He would always talk about the grapefruit. He’d grab a breast or buttock of a student and say, “Mggrmh” or “ripe grapefruit,” and he wiggled it a little bit. Today, he would never get away with it, I don’t think. [LAUGHTER] But he made you think that your pencil was on the skin, on the flesh of the student, of the model. He’d say, “Now you’re going to go over that flesh” and you’d try to feel that. But I didn’t feel it because I was too young to understand what he was talking about.

In that interview given to historian Mary Emma Harris in the 1970s, Ruth made light of her professor’s conduct in an era when students’ reactions were circumscribed by prevailing attitudes of the 1940s. It was more than half a century before the #MeToo movement emboldened young women to call out male authority figures for unwanted physical contact at school or work.

Ruth’s debut into Black Mountain society was reserved and even, in her own words, “antisocial.” She worked constantly, and was at ease in the company of other workers. As a young woman who had toiled as a domestic and saw herself as a person of color in the South, Ruth at least initially avoided the dining room and chose to eat in the kitchen with the cooks. Heady conversations over dinner could be intimidating. Mary Parks said it was the only time she ever wished she smoked. The gesture of lighting a cigarette could fill the awkward pauses.

Known equally on campus for her art and her elbow grease, Ruth had little time for dalliance amid the schedule of her work details. Her chores included milking cows and trucking milk from the dairy to the college in a converted weapons carrier. She was one of only a handful who knew how to drive the farm tractor. She churned milk to make sweet butter and buttermilk, luxuries that the European faculty craved. She made the bed for painters Willem and Elaine de Kooning. She also swept floors and worked in the college laundry. Her labor infused her art with new ideas: Ruth turned the BMC laundry stamp into a graphic design for a class project that later became a textile print for mattress ticking. She volunteered as the school barber, using skills she picked up from her parents’ homemade haircuts on the farm. Her service was free, though she asked for a ten-cent donation toward school fundraising, with discounts for needy cases.

Another student philanthropy effort she aided was Mush Day, when, once a week, students ate meals of gruel and potato soup to save money for donation to European postwar relief. Ruth was known for making piquant sweet and sour sauce to spice up the plain fare.

Up and out by dawn, Ruth kept farmer’s hours and maintained a Zen-like focus on her work. “She would get out there and break the ground for a garden . . .the heavy work,” Mary Parks recalled. “My job was making peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and punch.” Her early rising prompted Albers to request that she knock on his door at first light. He wanted to go outside in time to photograph the morning mist that veiled the mountains in progressively lighter shades of blue.

With nascent gender equality came a tentative embrace of minority students and artists.Heavy duties were nothing new to the farm girl from Norwalk, California. On the Asawa farm, her work included planting, harvesting, crating vegetables for market, housework, cooking, and stoking the wood fire to heat water in the ofuro (a traditional wooden bathtub). At Black Mountain, she found equally hard work—sometimes involving staying up all night to fix a furnace until the handyman arrived. It could also be dangerous. One day Ruth and others climbed a ladder to explore the inside of a silo just as stores of corn were being poured in. They narrowly escaped burial by an avalanche of corn.

It is a wonder she had energy for art. Ruth began a habit of napping after dinner and then pulling all-night creative sessions in her studio.

Albers would judge one secret of Black Mountain’s success to be its work program. Toiling side by side put men and women on a more equal footing and gave them a sense of self-sufficiency for life, he said. Years later, after leaving North Carolina to head Yale’s design program, Albers explained the virtues of the Black Mountain system in his own special idiom: “So the girls and the boys, they knew each other sweating. And not like here, when you come Saturday evenings together with new makeup only. Ja?”

With nascent gender equality came a tentative embrace of minority students and artists. As a progressive college in the South, where segregation was the rule, Black Mountain began early steps to integrate in the spring of 1944, admitting a single female black student to its summer music institute. The move split in half a faculty that sought the higher ground, but feared flouting the customs of the community. (Precedents for integration were rare and chilling: An Alabama seminary that had previously added black faculty had burned to the ground.)

But Black Mountain students pushed for more inclusion, voting two-to-one in favor of expanding black admissions to the regular 1944 fall term. By the time Ruth arrived in the summer of 1946, she saw both African and Asian Americans on campus, including fellow Japanese American student Isaac Nakata, a native of Hawaii, and sculptor Leo Amino, who was born in Japan. Black painter Jacob Lawrence came as a guest artist with his wife, Gwendolyn Knight. African American students like Mary Parks were safe within the island of campus. But the atmosphere changed when they ventured into town, where they still witnessed reminders of the segregated South in white and colored water fountains. That didn’t stop Ruth, after she turned twenty-one, from riding into town in a friend’s rumble seat to have a beer at Peek’s Tavern.

On campus, students and faculty of different ethnicities lived together more or less peaceably. However, Parks recalled that one father, on learning his daughter shared a dorm with a black student, summoned her home. “She was the sweetest girl,” sighed Parks.

Black students brought their histories of discrimination; Japanese American students, their experience of exclusion and incarceration. Parks remembered a Japanese American classmate sitting by the lake and telling her about the internment camps. It was the first she’d heard of them.

Ruth’s first six weeks at Black Mountain flew by. When autumn came and her scholarship money was gone, the administration searched for ways to keep the committed young artist at school. They found funds and awarded her a scholarship from an anonymous benefactor. She wondered about the identity of her sponsors. One was later revealed to be her classmate Lorna Blaine Halper, who had received money after her brother was killed in World War II. His sacrifice and her gift helped keep Ruth in art school.

Ruth was quietly gaining a reputation among faculty and fellow students as a camp survivor, a serious artist, and an Albers protégé. Painter Susan Weil, fresh from the Académie Julian in Paris, recalled:

Ruth was a beautiful, quiet person. The rest of us were students, but she was an artist. The school was small so you knew everyone. Two of my friends were Americans of Japanese descent who were put in camp . . . You can’t believe it. She certainly told us. But we didn’t talk about it. We were into the moment. She didn’t seem bitter. . . . She had Albers’s approval and that was unique. He didn’t think anybody was very good except for Ruth. He’d say, don’t take yourself seriously—you’re not artists. (But) I think he was respectful of her.

Weil’s opinion counted. After studying with Albers—and chafing under his tutelage— Susan Weil left Black Mountain with Robert Rauschenberg, heading north for the New York School, where they married and had a son. She was still painting and exhibiting well into her ninth decade. Weil spotted Ruth early as a powerful artist with a unique creative vocabulary.

__________________________________

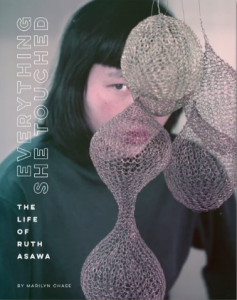

From Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa by Marilyn Chase. Used with the permission of Chronicle Books. Copyright © 2020 by Marilyn Chase. Photo: Untitled Looped Wire Sculpture, Ruth Asawa, De Young Museum Permanent Collection (via Wikimedia Commons).