Assimilation and 80s Punk Culture in Small-Town Pennsylvania

Phuc Tran on What Helped Him Survive Isolation

Fuck that kid.

That’s what I thought when I first saw Hoàng Nguyễn in eleventh grade. Hoàng never did anything to me, and he certainly never said anything to me. God, he hardly looked at me except when we passed in the hallways, me on my way to physics, him on his way to wherever. We’d glance at each other, give a quick nod, and move on, swept along in the rapids of our hallways. But fuck that kid.

Hoàng was a fun-house mirror’s rippling reflection of me, warped and wobbly. I hated it. I was Dorian Gray beholding his grotesque portrait in the attic, and I was filled with loathing. My disgust for Hoàng was complicated and simple at the same time: I was the Vietnamese kid at Carlisle Senior High School. Just me. Fuck that new Vietnamese kid.

Nestled in the Susquehanna Valley town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, Carlisle Senior High School sprawled as a monolithic mid-century modern block of types: archetypes and stereotypes. Industrial gray lockers ringed its hallways, the compartments narrow enough to repel most of your textbooks but wide enough to collect the trash and detritus from your backpack—your own personal landfill. Linoleum floors, classrooms with chables (the combo chair-tables of the 70s), blackboards, American flags, loudspeakers from which the wah-wah-wah of adult-speak would drone. Our school district was so large that the juniors and seniors had their own separate high school—the so-called Senior High School—and the freshman and sophomores had their own underclassmen high school building.

Carlisle High School stocked its seats and bleachers with a familiar cast from the 80s: the athletes who towered above the rest of us; the cheerleaders who lay supine beneath them; the geeks with their physics books under their arms; the preps with their Tretorns, Swatches, and impeccable Benetton sweaters; a handful of black kids with MC Hammer pants and tall, square Afros, tightly faded; punks and skaters with their leather jackets and black Converse; a few swirly hippies; the rednecks with their oily palms and cigarettes and trucks. Carlisle High School was another cultural cul-de-sac built with the craftsman blueprint of John Hughes, the Frank Lloyd Wright of teen malaise.

If you’re a Vietnamese kid in a small Pennsylvania town and you’re getting your ass kicked because you’re Asian, what does this mean? You go punk rock.

Overwhelmingly white, Carlisle’s population offered all the rainbows of Caucasia. The town’s main employers were Dickinson College, the Army War College, a smoky stack of factories, and the service industries that had sprung up to support the aforementioned trifecta.

In the spirit of public education, we progeny were all in the mix together: the itinerant army brats; the ivory sons and daughters of professors, doctors, and lawyers; the greasy offspring of waiters, cooks, and factory workers; and the token refugee family. The Trần family blended right into the mix like proverbial flies in the ointment. That is to say: we didn’t.

Carlisle’s glitter was unmistakably 80s, but its structure was straight from the postwar era, bricked together by the mortar of the 50s. We had a downtown Woolworth’s with a chrome luncheonette counter and red vinyl stools and a grand movie theater with its incandescent marquee. The four corners of Carlisle’s town square were righted by two courthouses and two churches (Episcopalian and Presbyterian). God and Law and Law and God. It wasn’t a subtle message to any of us living in Carlisle what was at the heart of the town.

And the pièce-de-résistance: our high school was the town’s designated Cold War fallout shelter. The blue-and-yellow radiation placards festooned our hallways, reminding us that we were only a button-push away from nuclear annihilation.

From what I gleaned on television, Carlisle seemed like a slice of American pie à la mode. We bottled lightning bugs on summer nights. Trucks flew Confederate flags. We loitered at 7-Elevens and truck stops. We shopped at flea markets and shot pellet guns. My high school provided a day care for girls who had gotten pregnant but were still attending classes. We stirred up marching band pride and fomented football rivalries. The auto shop kids rattled by in muscle cars and smoked in ashen cabals before the first-period bell. We were rural royalty: Dairy Queens and Burger Kings.

This was small-town PA. Poorly read. Very white. Collar blue.

So where did the immigrant Vietnamese kid fit into all of this?

By junior year, I had spent the last eleven years of school clawing my way to acceptance, at least in my own mind. As the only Asian kid in my classes and school through eighth grade, and then one of the very few in high school, I had been taunted and bullied in those early years. The blatant playground racism I bore in elementary school dipped below the surface in middle and high school, but it was always rippling under the social currents.

I believed that I was bullied because I was Vietnamese, so I did the math for my survival: be less Asian, be bullied less. Armed with this simplistic deduction, I tried to erase my otherness, my Asianness, with an assimilation—an Americanization—that was as relentless as it was thorough.

My plan for assimilation was a two-pronged attack, top-down and bottom-up. The top-down assault was my attempt at academic excellence.

In the trenches of high school warfare, honor roll and National Honor Society shielded me: even if I felt like a social pariah in my classes, at least I would have a better vocabulary than these philistines.

I realized that there was some prestige in being smart, or at least appearing smart. Sounding smart was not the same social Teflon as being good-looking or athletic or funny, but hell, if someone could give me some props for being good at school, I would take nerd props over no props at all. I got zero props for being Vietnamese or bilingual or a refugee. Operation Sound Smart commenced: I read voraciously, I studied tirelessly. I read as much (or at least name-dropped as much) of the Western literary canon as I could. Of course, I was a teenager—what the hell did I really know?—but my drive was as tenacious as my ignorance was deep. Being an intellectual gave me some clout in the classroom. And basking myself in the esteem of my classmates, I felt the warmth of their respect in sharp contrast to my cloaked envy of them. They belonged in a way that I never could, and their regard for me was sweet and sour. How Asian.

Then I hit the jackpot. Triple cherries. Working at my town’s public library as a library page, I bought a discarded copy of Clifton Fadiman’s The Lifetime Reading Plan.

In The Lifetime Reading Plan, Fadiman listed and summarized all the books that he thought educated, cultured Americans should read over their lifetime, beginning with the Bible and ending with Solzhenitsyn. The Plan listed the books and presented Fadiman’s synopses of the books’ merits and his justification for their obvious place in the Western canon. His introduction was unapologetically American, classist, and white—and I loved it. The Plan would be the most powerful cannon in my war for assimilation.

I now possessed the de facto manual for educated white men. Fadiman’s list of must-read books was a cheat sheet for those who wanted to be (or in my case, appear to be) erudite. In no particular order, I read what I could, sometimes with Fadiman as my docent, sometimes not: Flaubert, Twain, Kerouac, Brontë, Kafka, Camus, Ibsen, James, Thurber, Shakespeare.

But in the course of reading great books, something happened. My reading molded me, the tool hammering its hand into shape. By some miracle—and by miracle, I mean great teachers—I pushed past the shallowness and stupidity of my own motivations. I fell in love with the actual literature and the actual ideas of great literature. As an immigrant, as a Vietnamese kid, as a poor kid, I had collected so many scarlet letters of alienation that I connected profoundly to the great works.

As I read, I began to understand that all the great works wrangled with big questions, important questions: our place in the world, the value of our experience, the fairness and meaning of our suffering, our quest for love and belonging. Universal themes bound these great works together, and they bound me to their oaky, yellowed pages like Odysseus lashed to the mast of his ship. I felt a connective and humanizing reonance in books: I wasn’t alone in my aloneness. I wasn’t alone in my longing for love. I wasn’t alone in my fear of being rejected, my fear of never finding my place, my fear of failing. The snarl of my journey was untangled and laid out clearly by books.

In the great classics, there were so many moments for me to divest my age, my town, my skin, so many moments to be part of a universal conversation. Homer sharpened my mind’s edge. Dickinson gave me winged hope. Thoreau made a whole cabin for me.

With my academic assault underway, the second prong of my attack commenced: Operation Look Punk. You know one way to show that you fit in? By not fitting in. It’s a weird, counterintuitive trick—a social trompe l’oeil, if you will.

Here’s an analogy: In drawing, the way that you show perspective—the way that you make something look real—is by making things bigger in the foreground and smaller in the background. While the paper lies flat and two-dimensional, the exaggeration of certain aspects of the drawing makes the objects appear to have a third dimension. The medium has no depth, but the content does.

How do you do that in the social milieu of high school? You pick a subculture. Exaggerate some part of yourself, draw attention to it, and then all the other things will fade into the background. If you’re a Vietnamese kid in a small Pennsylvania town and you’re getting your ass kicked because you’re Asian, what does this mean? You go punk rock. Like, you go FULL PUNK. Get the leather jacket. Shave part of your head. Wear ripped-up flannel. Bleach your hair.

With my academic survival ensured in the classroom, my bottom-up assault was designed for social standing outside the classroom, and I pinned my safety on 80s punk culture.

I hated my parents. I hated my town. I hated the racism that made me hate myself. But through punk, I found my tribe.

Now the rednecks don’t want to kick your ass because you’re Asian; they want to kick your ass because you’re a social freak. Being a freak because of my weird clothes and hair was a respite. These were things that I had chosen—these were things that all my punk friends had chosen. Fighting rednecks because you were a punk was far better than fighting because you were Asian, and fighting with allies was far better than fighting alone.

Being an outsider because of my race was a burden that I didn’t choose. There was nothing I could do about it. On the surface, I seemed to be another angry teenager, but my anger wasn’t just swayed by juvenile impulses. I hated myself. I hated my parents. I hated my town. I hated the racism that made me hate myself. But through punk, I found my tribe. A group of people with whom I could bond over new skate tricks or the new Fugazi record or going to punk shows. We punks got to skip over superficial things like race and ethnicity. We talked about important things like where to get beer and how to pay for tattoos. For a kid whose days at school and nights at home were littered with the land mines of physical violence and emotional abuse, punk rock was close enough to love.

If you catch me in my off-guard moments, I’ll tell you that at some points in my life, I wanted to be white. It’s not a proud feeling, but it’s not a feeling that comes from the shame of being brown. It’s a tired feeling. Tired of the crushing racism. Tired of not belonging. It’s the exhaustion from fighting for your right to exist. Getting called a chink at any age is painful, whether you’re five, fifteen, or thirty-five. Damn it, I’m not even Chinese, but that didn’t matter.

Punk alleviated that exhaustion—or at least I thought it did. In my spiked leather jacket, Subhumans T-shirt, Doc Marten boots, and ever-changing haircuts, I forged the portrait of a kid who belonged, a kid who fit in by not fitting in, and even if that portrait ultimately turned out to be flat and shallow, it had the illusion of depth.

In Oscar Wilde’s supernatural novella, The Picture of Dorian Gray, the protagonist Dorian Gray maintains his physical beauty while a mysterious painting of himself, which he hides in the attic, ages and grows putrid and grotesque. Dorian pursues an immoral and decadent lifestyle, and while his physical appearance remains unchanged, the true corrosion of his soul is reflected in the portrait. The reader understands that the portrait is the real nature of Gray, but Gray’s beauty, his physical appearance, is no less real. As the novella unfolds, the reader wrestles with the reality of both Gray and his painting. What was real, his physical body or the painting of his soul? Wilde might say both, and when I read Dorian Gray, I recognized immediately the echoes of similar tensions in my life. Was the punk rock version of myself the real me? Or was the real me the one hiding underneath the punk rock?

By junior year of high school, 1990, I had achieved insider status, even if that insider status was with the outsiders. Then fucking Hoàng showed up.

He was fresh off the boat. His English was terrible while mine was impeccable. His teeth were crooked while mine were straight because of orthodontia. He had a bowlegged walk, probably because of early malnutrition from years spent languishing in third-world poverty. Having escaped Sài Gòn, my family had come to America in 1975. It didn’t get any more privileged than that. Hoàng’s clothes were ill fitting and clearly hand-me-downs.

When Dorian Gray beholds his portrait in the attic and shows his friend Basil the horror of the painting, Basil is sickened. The portrait reflects the rot of Dorian’s soul, and it repels Basil just as I was repulsed by Hoàng.

But it wasn’t him that I found repugnant. I hated everything he stood for. I hated that he was my portrait if my family hadn’t escaped Sài Gòn. Hoàng embodied my alternate reality. Nervous. Smiling. He made me feel a sick cocktail of emotions: shame, guilt, and sadness. He was an unflinching foreigner, walking down the hallways of my high school, oblivious to his foreignness. I hated how unaware he was. There was no art or artifice to his presence or appearance. He seemed grateful just to be in high school, and his gratitude was infuriating. Now kids would lump me in with Hoàng in spite of everything I’d done to rip up and spit out these expectations. Consequently, I spent the last year of high school avoiding Hoàng. By the time we graduated, we had merely exchanged only semaphores of quick nods and glances across a silent expanse.

Recently, I looked at my high school yearbook. My senior portrait is ridiculous. I have a huge Morrissey-style coif, a shitty tight-lipped smirk on my face, and a small skull-and-crossbones pin on my lapel. It’s so dated and silly, a picture that is as much a time capsule as it is an artifact of a young man’s hubris. I’m an angry teenager in the photograph, and I know every fold and wrinkle of that rage and loneliness.

I flipped the page from my portrait to Hoàng’s, then back to mine.

Hoàng Nguyễn’s portrait is as plain as it is unremarkable. His hair is short, and it is parted cleanly on the left. He stares just to the right of the camera, dressed in a simple blazer and tie. It’s the nicest outfit he probably has, and its simplicity gives the portrait a timeless feel.

You can’t look at it and pinpoint it to a specific era or trend. It feels generic, but in its generality, it feels universal. Its lack of guile is stark.

Hoàng smiles. His face is broad, wide, and his eyes—his eyes are full of hope.

__________________________________

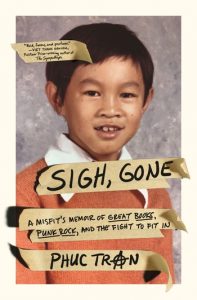

From Sigh, Gone by Phuc Tran. Used with the permission of Flatiron Books. Copyright © 2020 by Phuc Tran. Feature image: detail from Dan Witz’s mosh pit series.

Phuc Tran

Phuc Tran has been a high school Latin teacher for more than twenty years while also simultaneously establishing himself as a highly sought-after tattooer in the Northeast. Tran graduated Bard College in 1995 with a BA in Classics and received the Callanan Classics Prize. He taught Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit in New York at the Collegiate School and was an instructor at Brooklyn College’s Summer Latin Institute. Most recently, he taught Latin, Greek, and German at the Waynflete School in Portland, Maine. His 2012 TEDx talk “Grammar, Identity, and the Dark Side of the Subjunctive” was featured on NPR’s Ted Radio Hour. He has also been an occasional guest on Maine Public Radio, discussing grammar; the Classics; and Strunk and White’s legacy. He currently tattoos at and owns Tsunami Tattoo in Portland, Maine, where he lives with his family. Phuc is the author of the memoir, Sigh, Gone.