As the World Ends, Has the Time for Grieving Arrived?

Sue Sinclair on Poetry in the Age of a New Sadness

This winter I found five starfish on Middle Cove Beach. I’ve been visiting Middle Cove since my family moved to Newfoundland in 1978. We used to go after supper, and I’d hunt for fool’s gold. If there was a storm at sea, kelp and urchins washed up from the deeper waters, but I’d never seen a starfish before, not one, and certainly not five. They were a pale wintry purple flecked with white. Here’s the difference between me when I was child and me now: my heart sank when I spotted the starfish. Art critic Dave Hickey says that when we find something beautiful, we want to share it with other people; we want to grab someone and say, Look! But although I found those starfish beautiful, I didn’t want to share them. Instead, my chest felt a little tight. And I felt dissociated from their beauty. I couldn’t feel it, take pleasure from it.

The next day I read a news report about a wave of benthic creatures that had washed up dead on the beach in St. Mary’s, Nova Scotia, the day before: dead lobster, dead crab, dead mussels, dead worms, dead urchins, and, yes, dead starfish. No one knew why. This wave of death followed on the heels of a surge of dead herring, also unexplained. And I thought, I was right. There was something awful about those starfish. I knew Middle Cove was a long way from St. Mary’s, but my chest tightened again.

It turns out I probably wasn’t right. I called Ted Leighton, the retired veterinary pathologist who was quoted in the news reports I had read. He told me that the Department of Fisheries and Oceans had tested for a huge variety of diseases and poisons but hadn’t turned up a cause of death. He thought the deaths could be explained in terms of normal natural processes, and he went on to make just that kind of explanation, convincingly.

This should have been a relief. But the starfish showed that something had changed in me. My gut reaction to finding a handful of unusual creatures had shifted from delight to dread. I realized I was carrying around a load of barely conscious, anxious anticipation. It makes me think of these lines from Karen Solie:

An inaudible catastrophic orchestra

is tuning, we feel it in the air

impelled before it, as a pressure

on the brain.

On the beach, I became aware of the pressure on my brain.

Even though Leighton had delivered good news about the starfish, the good news felt provisional. It’s only a matter of time before I encounter some other aberration that justifies the tightness in my chest. So I didn’t exactly feel relieved. I was also not relieved because a tiny perverse part of me wanted to have the dread confirmed. Selfishly, I wanted all the talk of climate change to turn into something material. I wanted it to hit home. I felt that literally: I wanted it to hit my home. That was also the last thing I wanted. To me, this experience with the starfish seems to have taken place on the near edge of what Tim Lilburn calls “a new sadness.” He writes,

The nature of the sadness that is and will be experienced in the face of the effects of global warming . . . struck me as unlike anything in memory or imagination. It occupies an entirely new category. Though it may contain aspects of malaises we know quite well, like regret, nostalgia, penthos, depression and despair, there [is] an unnamed something else; it seems as a whole to be other than conditions we are familiar with, other even than these in novel arrangement, with an unidentified intensifier.

I glimpsed this new sadness. Others have had more profound experiences of it, and I feel almost envious as I write because it seems these people have a clearer view than I do, are more intimate with reality, though it’s at a cost.

What is the reality? Climate change is stoppable, but enough has changed that there are already consequences—Canadians have only to look to our melting Arctic ice to see them. And because of the warming oceans, there will be more consequences even if the global community cuts all carbon emissions this minute. It may be possible to reverse climate change by harvesting carbon from the air, though no one is sure where to put it afterwards, and it’s not clear that the political will exists to take any of these measures, especially given the current fate of the Paris Agreement.

Do we need to muster the political will required to take the measures still available? Absolutely. But do we also need to consider how to encounter the reality of climate change, how to feel it, how to live with feeling it? I think we do, though it scares me. T.S. Eliot wrote in the opening to “Four Quartets” that “human kind / cannot bear very much reality.” I used to think he was writing about other people, about a rule to which I was an exception, but I’m humbler now and see myself in his words. I can handle only so much.

I think I might have to learn to handle more, though. Even if I don’t volunteer, I expect to be conscripted soon. And the tiny element of envy I’ve found in myself suggests there may be something in it for me. For if it’s true that we can only deal with so much reality, being numb is its own kind of pain. This January, after covering climate change for the Guardian for five years, Michael Slezak wrote an unusually personal article, “Writing about Climate Change: My Professional Detachment Has Finally Turned to Panic.” An excerpt:

Until recently, like a sociopath might have little feelings [sic] when witnessing violence, I’ve managed to have relatively mild emotional responses to climate change. . . Intellectually I’ve understood the things I’ve been reporting and the inevitable disaster that is looming for much of the world’s population. But somehow, I didn’t feel the deep sense of panic or dread that is obviously appropriate when facing such a serious crisis. But in 2016, something changed.

He describes what he thinks might have precipitated the change, then writes:

But the new emotional reaction I’ve developed to climate change, while obviously unpleasant, also comes as a kind of relief.

That panic may bring relief is odd, but I get it. Becoming emotionally in touch with the reality he was reporting made Slezak whole—at least as whole as any of us might claim to be. His thinking, his body, and his emotions fell in line. Furthermore, he was in a more intimate relationship with the drought- and fire-ravaged landscapes he was reporting on, in the sense that he made himself vulnerable to them, allowed them to act on him. So he was fully engaged with the world around him. And that kind of engagement offers a measure of well-being. The catch is that in the case of climate change, the intimacy is tied to tremendous distress.

Many Westerners are in a state of denial about climate change—I include myself here. I’m not an outright denier, but I tend to fall into the category of what Jonathan Rowson calls “stealth deniers”—those who “accept the reality of anthropogenic climate change” but don’t “appear to have the commensurate feelings, sense of responsibility or agency that one might expect.” In Rowson’s study of the British population, 19.6 percent were outright deniers (what he calls “the unconvinced”) and 63.9 percent were stealth deniers, like me. I’m what Rowson terms “an emotional denier.” I, along with 47.2 percent of the stealth deniers he identified, have trouble connecting emotionally with the reality of climate change. I’m Slezak circa 2015, the one who didn’t panic. But the encounter with the starfish led me a little ways out of that numbness, and in a way it felt good, even as my body tensed up and my breath shortened.

Denial, in any case, might show that I’m on the threshold of mourning, just overwhelmed by it . . . which could mean that I’ve crossed into it without knowing. For although there are myriad theories about how mourning is experienced, and certainly people mourn differently, denial is often an early stage. So as a denier who glimpses grief, I may be on my way to a richer, more painful engagement with the dying world—which I both want and don’t want. I want it for the reasons I’ve given already—I want to feel integrated as a person and wholly engaged by my environment. But I also want it for moral reasons. Philosopher Simone Weil has written that “to know that this man who is hungry and thirsty really exists as much as I do—that is enough, the rest follows of itself.” Weil’s point is that actually, vividly grasping the reality of another being leads straight into a moral relationship of care. That’s one reason I want to step further out of denial. Then there’s Lesley Head’s argument that truly grieving climate change, and the selves that will be stripped from us in the process, can free up emotional energy to be invested in more creative ways. “Bearing our grief will not necessarily stave off catastrophe, but it will give us a better chance of effective action,” she writes. What exactly constitutes effective action will vary depending on the situation: it could involve a variety of actions aimed at stopping or even reversing climate change; it could also be a matter of keeping vigil and offering to our human as well as our animal, vegetable, and mineral companions what palliative care is possible now that global warming is underway.

We need to think about what vigil and palliative care might look like, for these are becoming increasingly necessary forms of action. Head notices that “we are systematically excluding the more extreme parts of future projections from our consideration, just because they are so difficult.” She suggests that some of our preparatory efforts “must go into emotional preparedness for things that may be extremely unpleasant.”

This takes me back to poetry. I’m not foolish enough to think that poetry is The Answer to climate change, or even to the question of how to live with the escalating pain it’s causing. But as a poet, I have to wonder what it has to offer, how it can help me to shift out of denial, and how it may support me as I move deeper into the work of mourning. For poetry is often a part of mourning. As Don McKay has observed, poetry is one of those things that seems expendable in a fast-paced world where we live so much on the surface. It roars to the fore at crucial moments of life where we want language to step up and acknowledge significant events and feelings—birth, death, love . . .

Even people who don’t otherwise read or listen to poetry will often look to it for support in the face of death: poetry is often a part of vigils, eulogies, funerals, memorials. It can support us in so many ways that I can’t hope to write about it comprehensively. But here are a couple of things it can do.

It can help with denial by making loss feel real. Jorie Graham has said that in America, a coup has been enacted “upon the reality status of events and of people and therefore on nature itself.” “The state of emergency,” she says, “is this: this not-even-feeling-it-is-there, the not-even-feeling-others-are-real.” Poetry, she thinks, can try to break through, “to make reality feel real.” I feel that power in poetry. I feel it when Graham writes,

—&

one day a swan appeared out of nowhere on

the drying river,

it

was sick, but it floated, and the eye felt the

pain of rising to take it in—

I can’t help but imagine that swan partly because Graham’s poems sweep me up into their stream of consciousness. And partly because the acknowledgment that it really is painful makes it easier for me to let the swan in.

Or consider this call to reality in Jan Zwicky’s poem “Seeing”:

You,

you who are weeping,

look up: it’s the sky.

And the rain that is falling

is rain.

This poem sees the pain involved in witness, sees my tears, and offers reality as a consolation: there’s still something here, it says. And the reality of even a broken world is some consolation.

Poetry could also help to build the radical new kind of hope that Lesley Head suggests Anthropoceneans need. We’re used to thinking about hope as the imagining of a bright possibility, a rich future. But the resilient people she imagines “disconnect hope from emotions of optimism, and from an unfolding future. They find hope in practice and being.” Hope in the age of consequences may be in the act of coping as best we can with an impoverished, even disastrous present and future. As Robyn Sarah writes in “As a Storm-Lopped Tree”:

The chainbelt of time

runs around and around.

Moon walks where it wants to,

like cats in high places.

Sun gilds the buildings . . .

And moments of animal well-being

may be all that’s left us, may well be.

To be grateful for neutral days.

And here I go back to the starfish I found on the beach. Because I’m troubled by the fact that in the same moment that I broke through my general denial of climate change, I found myself distanced from the beauty of those starfish. I could see it, sort of—but I certainly couldn’t feel it. And I think the dampening of the effect of beauty on me wasn’t just the result of a dissonance between beauty and the awfulness of climate change. I think it was also a protective instinct: I didn’t want to attach to, care about, the beauty of a nature that was vanishing.

But Jan Zwicky’s poem “Seeing” has helped me to feel braver about this. It has helped me to see how it’s possible to open oneself to a disappearing beauty even as it flickers on the edge of extinguishing. She, like Sarah, takes up the language of gratitude:

Even now, even now,

to fail to give thanks: the same

lethal refusal, same

turning away from the beauty that is.

I don’t want to fail doubly, to fail again in the midst of the failure that is climate change. “Seeing” inspires an openness in me, and I hope it will charge my next encounter with the reality of global warming. That hope is part of how I imagine Head’s “hope in practice and in being.” Even if the hope of evading ecological suffering and loss has gone extinct, I can hold on to the hope of engaging fully with the dying in a palliative spirit. And part of that engagement is to be fully present and available to whatever beautiful detritus I next find at the beach.

__________________________________

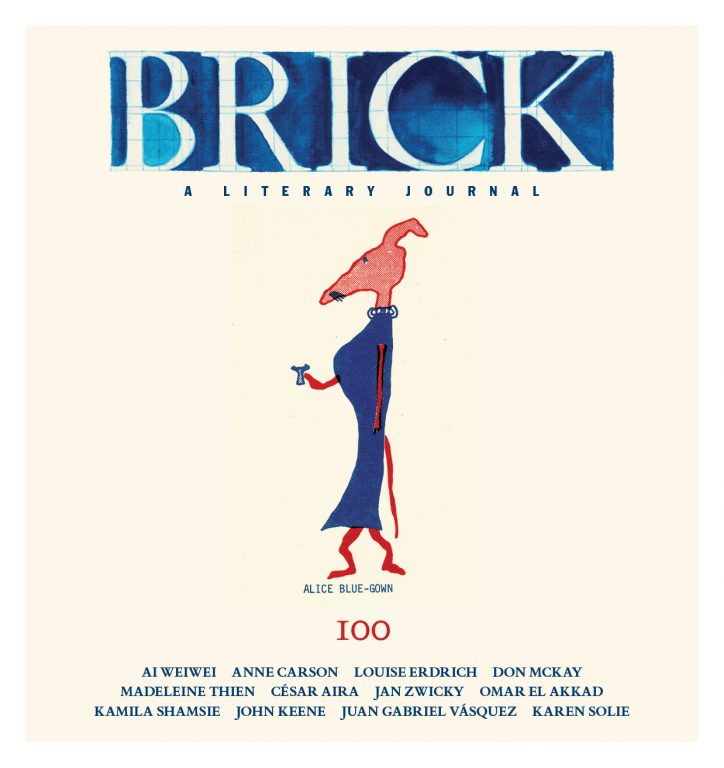

This essay appears in the 100th issue of Brick Magazine.