As The Met Reopens, a Former Employee Longs For Its Art

Christine Coulson on Certain Pleasures Nature Doesn't Afford

I have seen the Instagram sunsets, the perfect daffodils, the lines of upright tulips, the misty beaches, the blooming trees, the fragile baby ducks. I have seen Jasper Conran’s videos of splendid morning walks through his English garden offered to soothe those who don’t have access to such abundance. Architect Ben Pentreath’s landscape videos look similar, verdant and lush; I suspect the two are neighbors and go to the same pub. I have seen Hawaiian waterfalls and placid, reflective lakes at dawn. I have seen them all.

But I am an urban creature, addicted to the hum and whir of city life: cafes, movies, museums, bad performance art. Noise. I like ritual within chaos. I remain fixed and stolid—eating at the same three restaurants, walking the same favored blocks, keeping to my disciplined routine—as New York whips its relentless creativity at me with astounding speed. And I respond. Is there anything more exhilarating than sitting in a glittering bar with friends after seeing a terrible film or a wonderful play together? I cried for days unprompted after the shock of seeing The Ferryman on Broadway.

I am now sheltering in the country and struggling. Nature is beautiful and fortifying and hopeful at this time of year. Yes, each bloom is its own little magic miracle. But that’s all. Nature is ever giving and alas, while comforting for many, maybe too predictable for me. I know there are gardeners out there with an intimate relationship to their careful plantings. But there’s no hustle and bustle with nature, just a kind of respect and reverie. I would love nothing more than for an old elm tree to lurch forward one day and say a tired, slightly annoyed “Fuck you.”

Art is different. Of all the things my city throws at me, it’s the art that gets my heart racing. I worked at the Metropolitan Museum for over 25 years and the objects in that collection never let me down. I am desperate to see them again. The real things, not the online images. I know the objects are where I left them. But they change with each viewing and always reward you with more looking—and most importantly, more thinking. Each time you stand before them, they expose something new—often because you’ve changed in the face of their endurance.

There’s a 3rd-century BC statue in the Greek Galleries of a little girl holding a pet in her gathered-up toga. The stone folds have been worn over time, but the sculpture’s tender gesture is so genuine, so sincere. My stomach flips whenever I see her, a sublime and powerful example of the persistence of humanity. The collection holds Greek statues of much greater importance, but this one collapses time so potently. The sense that that little girl and her clutched fists of fabric truly existed, along with the individual human hand that captured her spirit in that moment.

Marble statuette of a girl, 3rd century B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Marble statuette of a girl, 3rd century B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

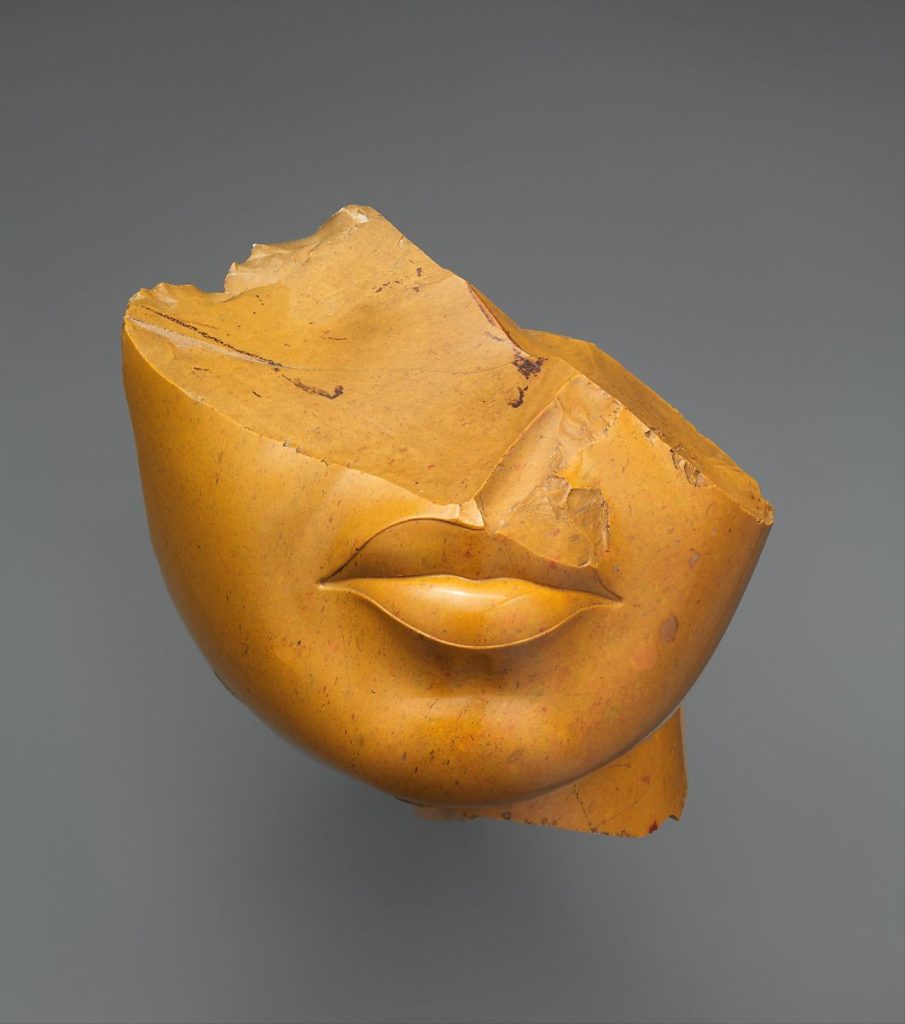

I’m often asked to share my favorite work of art at the Met, and I never hesitate. The ancient Egyptian head of a queen emerges from an extraordinary piece of yellow jasper (I know, nature again). Only the lower half of the life-size head remains; the sculpture was broken below the nose, leaving behind a presciently modern fragment of exquisite lips. Precise and fluid lines, uninterrupted by any evidence of time, articulate that mouth in its serene balance. A delicate sheen covers the polished surface of mustard-colored jasper.

She looks as though she was carved last Thursday. Ancient in her reality, modern in her broken state, she remains both universal—a monument to a pure and constant beauty—and absolutely specific. If I saw that woman on an elevator, even from six feet away, I would recognize her immediately. And that’s no accident. That is an artist at work.

Fragment of a Queen’s Face, ca. 1353–1336 B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Fragment of a Queen’s Face, ca. 1353–1336 B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

My childhood favorite was a medieval reliquary that held what was supposed to be Mary Magdalene’s tooth embedded in rock crystal and surrounded by gold filigree, like a dental trophy for best extraction. What attracted me then was likely the creepy molar in a glamorous setting, and the homemade, overwrought look of the thing—a really well-done school project.

What strikes me now is the religious conviction that this odd object represents. I admire the profound faith required to suspend disbelief in that holy tooth and its monumental story. It is human intervention at its most trusting—and most manipulative. A letter in the Met files suggests that the tooth belonged to a pig.

Reliquary of Mary Magdalene, 14th and 15th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Reliquary of Mary Magdalene, 14th and 15th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

However, if I could visit my museum today, I think I would race to see Lucian Freud’s naked portrait of Leigh Bowery. The six-foot canvas can barely contain the figure’s bulk of raw flesh, seen from behind, leaning forward with a tired, lumbering consent. I love the picture’s sleepy heft and feel it like a lonely embrace. Few artists assert themselves as strongly as Freud does with his thick and sticky layers of pigment and paint. He seizes upon both our vulnerability and our strength with the sheer persuasion of materials. Nothing natural about it.

What are all these objects doing while the Met is shuttered and we’re not there? I suspect they’re calmly curious. Those works of art are witnesses to history. At times, the Met’s grandeur sterilizes the fact that those objects have actually seen the many years that have passed since their creation. They have made it to the ultimate retirement home: survived wars, revolutions, woodworms, ancient tombs, piles of dirt, the bang of vacuum cleaners, trunks of cars, lonely decades in storage, and the Black Death itself to land in the galleries of a magnificent museum completely devoted to their care.

You see, art shows us the power of people to make, to express, and to, ultimately, leave something of themselves behind. Art propels my city because the need to reveal ourselves propels humanity. So, I suppose I’m tired of the miracle of nature. I want something that distinctly doesn’t happen automatically. Something that can be bold and delightful and awful and artificial. Something that is thrown at me by the breathless force of its creation. Something that comes from talent and from inspiration and yes, from that ever-elusive thing these days, the human touch.