Anxiety and Responsibility: What Stories Can Come From Our Current Moment?

Clare Pollard on the Urgency of Writing About Now

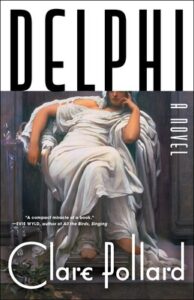

My debut novel, Delphi, is set during the pandemic. As soon as I say that, I imagine your reaction—you can’t think of anything more tedious, given you just lived through it; you turn to fiction for escape; it’s too soon; pandemic fiction is ubiquitous and “over” already. The suspicion that writing a novel during lockdown was a distraction for the underemployed middle-class also gives this subject a particular taint (Zadie Smith wrote in Imitations: Six Essays of there being “no great difference between novels and banana bread”).

But fiction is about society. How do you write contemporary fiction without acknowledging the force that reshaped all our social interactions over the past few years, from our working lives to our closest relationships? Any contemporary novel that doesn’t acknowledge the pandemic is just alt-history or fantasy.

It’s worth acknowledging that there has always been anxiety around the concept of writing about “now.” Writers’ block, during times of historical change, seems a recurring problem—it can be hard to be inspired by what you’re living through, with it feeling too real or unprocessed. And is making a sellable text out of a wider tragedy inappropriate, or glib?

Adorno famously declared that: “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” whilst I vividly recall Martin Amis writing that: “After a couple of hours at their desks, on Sept. 12, 2001, all the writers on earth were reluctantly considering a change of occupation.” In recent years another problem has been cited—reality has simply become too unlikely for fictional realism to keep pace with it. Ian McEwan’s post 9/11 remark that “American reality always outstrips the imagination” feels increasingly true.

In the poetry world, where I’ve spent most of my adult life, we are also aware of Ezra Pound’s assertion that literature “is the news that stays news,” and there is concern around whether texts will date. Will the reader of the future understand our allusions? I know an editor who refuses to publish poems with brand names in them, and it’s certainly true that pop-cultural jokes can go stale quickly (as a writer watching this year’s Oscars chaos, I couldn’t help but be aghast that, everything else aside, Chris Rock made a GI Jane joke in 2022).

How do you write contemporary fiction without acknowledging the force that reshaped all our social interactions over the past few years?

Another concern in writing about now—very legitimate I think—is that in the middle of something it’s hard to see its true shape. How are we to end our story, or draw the correct conclusions? The poet Hannah Sullivan has been working on a poem about the 2017 Grenfell Tower fire, and speaks interestingly about this. There were urgent, moving responses from poets at the time—such as Jay Bernard’s collection Surge (2019). But, once the immediate moment passed, Hannah felt that she needed to wait for the public inquiry before she could finish her own poem: for as much of the full truth as possible to emerge.

Certainly, the best second world war novels, from Waugh’s Sword of Honour series to The Tin Drum, weren’t published until the 1950s, (with my favorites, Catch-22 and Slaughterhouse 5 appearing in the 1960s), whilst, War and Peace was written 50 years after the French invasion of Russia. Can clarity only come after the settling of dust?

But if those are the risks, are there also benefits to writing about now? The first and most obvious advantage is that no one has written about now before. And, relatedly, writers won’t have read lots of accounts of it already. Describing the current moment makes literature more likely to be first-hand, fresh, lacking cliches, and even utterly original—new forms and styles often arise to meet their time.

Think of how the First World War allowed Modernism to smash through Victoriana, and scrabble up something new from the ruins of Europe. You’ll never be the first person to write a poem about a daffodil, but you might be the first to write about working in a supermarket during Covid-19, or today when [insert X] happened. The newness of the subject matter—the radical blankness of the page—can be inspiring

Secondly, the impulse to bear witness drives many artists, meaning the pandemic felt like an occasion we had to rise to. We are living through extraordinary times, in which a series of huge global events are simultaneously occurring. Aren’t we glad that Fitzgerald bore witness to the Jazz Age, and Steinbeck to the Great Depression? I always remember Anna Akhmatova’s introduction to Requiem, in which she recalls (in the excellent translation by Stephen Capus) how:

In the terrible years of the Yezhov terror I spent seventeen months queuing outside the prisons of Leningrad. On one occasion someone “recognized” me. It was a woman who was standing near me in the queue, with lips of a bluish color, and who, of course, had never before heard my name. And now, waking from that state of numbness which was characteristic of us all, she quietly asked me (for everyone spoke in a whisper in those days):

“And can you write about this?”

And I replied:

“I can.”

And then something like a smile flickered across what was once her face.

Article continues after advertisement

Avoiding modern times can be an abdication of responsibility then. Looking away from current events is political in itself. Nature writing is a case in point: you may say you want to write about the eternal—the rose, the lamb—but that is to pretend nature and the seasons are eternal and not shifting. To write nature poetry without the thrum of climate disaster in the background is in itself a form of denial and complicity. There are no apolitical poems or novels; no writing that isn’t a product of its time. To write about an office, a romance, a holiday, is utterly different post 2020: the flirtation and meeting and airport are each charged differently.

So if we accept there are pitfalls but decide to do it anyway, what are the strategies writers can use to engage with the news successfully? The first is embracing the idea of the poem or novel as journal—if you don’t know how history will look back on these events, you can at least capture what it feels to be alive this minute. I’m shocked by how quickly people have normalized the pandemic and our governments’ response to it—how easily they write off those lockdown months as a period when “nothing happened,” when in fact the unthinkable happened. So one of the things I wanted to do with Delphi was write it down before everything became faded and familiar.

All we know we have is each other and this shared moment, which we must try to witness, love and comprehend.

I really value poems that have a diary-like texture, such as Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems—far from the name-dropping and brand names dating them, they read like tiny time-capsules, transporting me to the 1950s New York of Lady Day, construction workers and cheeseburgers. Louis MacNeice’s Autumn Journal (1939) feels important, capturing as it does the rise of fascism before he knew how events would play out, as does Christopher Isherwood’s novel Goodbye to Berlin, also published in 1939. Recent novels like Olivia Laing’s Crudo, Jenny Offill’s Weather and Patricia Lockwood’s No One is Talking About This all have that same intense, prickly energy: a sense even the writer doesn’t know, as they are writing, how this historical moment might unfurl.

These books also all draw on another related strategy, which is not to write about history head on, but to let events creep into the story’s edges: think of Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair, in which an adulterous love-affair is intensified by the backdrop of the Blitz, or Virginia Woolf’s The Waves or Mrs Dalloway, both of which both are and aren’t ‘war novels’. In Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World, Where are You, the lockdown at the end caught me—as it caught us all—by surprise.

And there are other ways to reflect your times once you abandon realism. Poets often use allegory or metaphor, and novelists can too—George Orwell’s Animal Farm allowed him to reach an audience who would have surely swerved a novella about events leading to the Russian Revolution. His novel 1984 similarly creates an alternate world, albeit one projected into the future. As 1984 reflects 1949 by looking at how its political arguments could play out, so Sarah Hall’s brilliant Burncoat and Hanya Yanagihara’s To Paradise have recently entered into the pandemic-lit market by imagining alternative plagues, then thinking about ways they could reshape the world.

At the same time though, I must admit I am tiring slightly of sci-fi climate novels, pushing as they do concerns further into the future, and wonder if fiction needs to find new ways to engage with the sixth mass extinction happening right now. Which is to say: perhaps there is no future. All we know we have is each other and this shared moment, which we must try to witness, love and comprehend.

__________________________________

Delphi by Clare Pollard is available from Avid Reader Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Clare Pollard

Clare Pollard lives with her husband and two children in London. At nineteen, she published her first book of poetry, The Heavy Petting Zoo. She has since published four more collections of poetry with Bloodaxe, most recently Incarnation. Her play The Weather (Faber, 2004) premiered at the Royal Court Theatre. She has been involved in numerous translation projects, including co-translating The Sea-Migrations by Asha Lul Mohamud Yusuf (Bloodaxe, 2017) which received a PEN Translates award, and translating Ovid’s Heroines (Bloodaxe, 2013), which she toured as a one-woman show in the UK. She is the poetry editor for The Idler and the former editor of Modern Poetry in Translation. Her most recent book was a nonfiction title, Fierce Bad Rabbits: The Tales Behind Children’s Picture Books (Penguin). Delphi is her first novel.