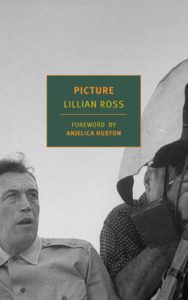

Anjelica Huston on Finding Her Father in the Writing of Lillian Ross

"She maintains her own integrity and she respects

the integrity of her subject."

During his lifetime and after his death, much has been written about my father, John Huston. The stories have abounded, often from first-hand witnesses, working partners, ex-wives, girlfriends, rivals, fellow-journeymen, and strangers. He has transcended biography on occasion and even been presented in the form of a novel. Among other things, he has been described as a hedonist, a womanizer, a man’s man, a sportsman, a gambler, a practical joker, a drinker, and an adventurer. On many occasions, he has been compared to Ernest Hemingway, which I think does neither of them a great service.

What seems to me the great disappointment of these somewhat superficial, often spurious comparisons, is that, somewhere in all the adjectives and descriptions, an essential point is lost. My father was all these things and more. He was an artist. It was my father as an artist that fascinated Lillian Ross. She never sought to write gossip or to go beyond a particular line that she drew for herself in his personal life.

In May of 1986, my father asked Lillian to accept the Brandeis University Creative Arts Award in New York City on his behalf, as he was recovering from eye surgery. She told the Creative Arts presenters:

Throughout his life, he has looked intently at, and continues to look at, the art, in all its forms, of other artists, from the earliest time to the present. He looks at art in the happiest of ways: with his entire being and without intellectualization. And whenever possible, in the case of living artists, he transmits to its creators, with his own Hustonian enthusiasm, his utter joy and astonishment at what he sees.

Much the same can be said of Lillian herself. They shared a boundless interest in life. I remember flying to New York with my father in 1986. He was very ill at the time, permanently connected to an oxygen tank in order to stay alive. Journeys of this kind were always touch-and-go and the consequences life-threatening. I was worried. We arrived in New York late at night. My father was pale and exhausted. The next morning, I was awakened from a deep sleep by the telephone. It was 8 am. “Lillian and I are off to the museums. Want to come?”

“As soon as another human being permits you to write about him, he is opening his life to you and you must be constantly aware that you have a responsibility in regard to that person.

I hadn’t been born yet when Lillian came out to California to write Picture, her account of my father’s making of The Red Badge of Courage. After the publication of Picture, her friendship with my mother and father not only continued but flourished, until my mother’s death in 1968 and my father’s in 1987. I grew up hearing about Lillian and meeting her from time to time. My parents loved and respected her, and trusted her. She was, they would say, different from other reporters.

A key to that difference is, I think, revealed in her statements about her principles in the introduction to her book Reporting. She writes:

As soon as another human being permits you to write about him, he is opening his life to you and you must be constantly aware that you have a responsibility in regard to that person. Even if that person encourages you to be careless about how you use your intimate knowledge of him or if he is indiscreet about himself or actually eager to invade his own privacy, it is up to you to use your own judgement in deciding what to write. Just because someone “said it” is no reason for you to use it in your writing.

Your obligation to the people you write about does not end once your piece is in print. Anyone who trusts you enough to talk about himself to you is giving you a form of friendship. You are not “doing him a favor” by writing about him, even if he happens to be in a profession or business in which publicity of any kind is valued. If you spend weeks or months with someone, not only taking his time and energy but entering into his life, you naturally become his friend. A friend is not to be used and abandoned; the friendship established in writing about someone usually continues to grow after what has been written is published.

Lillian’s writing is the proof of what she says. She maintains her own integrity and she respects the integrity of her subject. She never stoops to gossip or speculation. Her powers of observation are immense.

In the country recently, my husband, Robert Graham, and I were reading Picture aloud to each other. We were laughing and having a lot of fun when suddenly I realized that reading this book was like being in the same room with my father again.

I thank Lillian for her marvelous and timeless documentary—and for this portrait of my father, with all his changing profiles, as observed by one who shared his talent for beauty, humor, simplicity, and truth.

![]()

Foreward taken from Picture by Lillian Ross. Copyright © 2019 by Anjelica Huston.

Excerpted with permission from New York Review of Books. All rights reserved.

Anjelica Huston

Angelica Huston is an actress and director. Born in Santa Monica, California, she is the daughter of John Huston and the ballerina Enrica Soma. Huston began acting in the late 1960s, taking small roles in her father’s films, and in 1985 won the Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her performance in Prizzi’s Honor. She went on to have roles in numerous films, including The Addams Family, Ever After: A Cinderella Story, and The Royal Tenenbaums. Huston’s directorial debut was Bastard Out of Carolinain 1996, followed by Agnes Browne and Riding the Bus with My Sister.