Today is the day. No way will I be the mother of all bitches, no way will I bite off the passengers’ heads.

So much for good intentions. My pledge to be a sweet girl, made as I set out early for work that morning, didn’t last till noon.

I got through the morning rush, but then instead of slackening, passenger traffic grew to a flood. What’s up with this? I wondered. And then I realized it was Buddha’s birthday, April 8 by the lunar calendar.

As always, the load was manageable as we set out from the East Gate, but on the return trip the bus would be packed by the time we got to Kwangnaru. Kuŭi, Mojin, Hwayang, Togyo—every stop looked like a marketplace, so many people had mobbed there. Mobs of people were always getting on and off at Hwayang, but Togyo was a different story—we don’t stop there unless people are waiting, which happens three runs out of ten, but today, guess what—there must have been a good dozen people waiting each time. And at Sanghuwŏn, where the Ttuksŏm line joins ours, there’s always a throng, so our cargo practically doubles.

Next are Sŏngdong, Ŭlchi, and Wangshimni, and Wangshimni is no problem on the return route because people going downtown can catch the streetcar there. And then it’s Majang and Yongdu—two stops where there’s often so much of a crowd I have to leave some of them behind.

The people who take my line, the Kwangjang line, are always the same bunch—working stiffs at the lower end of the wage scale, but compared with the sleazy and wretched makeup of the outlying neighborhoods served by our line, they’re positively high-class.

Since our line seems to have been put in exclusively for the women going down to market carrying their baskets of goods on their heads, these women get their use out of it, and then some—they use it, they like using it, and they use it exclusively. Great for them, right?

It’s a rare day when a bus doesn’t break down somewhere in the city, and it’s a rare bus line that doesn’t have at least a few of these women among the passengers.

We have a lot of passengers coming downriver from as far out as Kwangju—peddlers, farmers, and god-knows-who. Morning and evening we have quite a few students. And then there are the miners—supposedly there’s a couple of big mines out in the vicinity of Songp’a, in a place called Mongch’on or something like that, and when these guys have money in their pockets they come into town for a good time.

“Lookie here, don’t tell me you’re off to Seoul to see the sights”—that’s a Chŏlla miner sounding off. “How’d I ever end up a friggin’ miner?”—and that guy sounding like a screech owl has to be from Kyŏngsang. You’ll always see this bunch with their britches hanging loose, Japanese rubber footwear, either shoes or knee-high boots, and a towel tied around their forehead.

So with the regulars alone the bus is always jam-packed to begin with, and the passengers get jostled around. But today, with all these extra people out and about, it’s twice as crowded—can you blame me for being surprised?

Among this bunch who’ve come crawling out of the woodwork, most are womenfolk—old women and young ladies. The way they’re dressed is so gaudy. It kills me the way the young ones fancy themselves. The old ones aren’t as bad. Just when I’ve recovered from the shock of the women in their quilted chŏgŏri of pink Japanese silk and their skirts so dark blue they look like they’ve been dyed with bugs, along come the ones in their unlined summer jackets. I feel like asking if that’s all they have to wear for viewing all the colorful paper lanterns hung on this special day.

Whatever they’re wearing, it makes me wonder if until today all these clothes were wrapped up deep inside a hope chest, waiting for their wearer to get married off, but more than the clothing tucked away in the hope chest, it’s these women all gussied up for their grand outing, who’ve been buried off in the sticks somewhere and only today are coming out of hiding to see what the world looks like. For all I know they’re mostly healthy, good-hearted, salt-of-the-earth people, but today, with their hairdos coming apart, their grimy, sun-darkened faces, splotched makeup, and claw-fingered hands, there’s no way you could consider them beautiful.

Most of them wear straw sandals, a very few have Korean rubber shoes, and believe it or not, there’s the occasional woman shuffling around in geta. The ones in geta are having a heck of a time maneuvering, they’re obviously not used to them—you might find it funny, but to me it’s a miserable sight. And it’s on account of those clack-clackers that a little incident occurred.

The bus had stopped at Mojin, and among those who shouldered the competition aside and made their way on were a young woman who even among the countrified looked as country as you get, and an older woman I guessed to be her mother-in-law.

We took off, but only a short distance later the young one bawled out, “Oh for heaven’s sake, my geta!”

It seemed her shoe had come off in her panic to board, and only now did she realize it.

Right away I pressed the buzzer and the bus lurched to a stop. The bus was so packed I couldn’t have opened the door, so I jumped out a window, saw that clack-clacker lying a short distance off, next to the streetcar track, ran to get it, then crawled back through the window and returned the clog to its owner. I saw gratitude in her face, but she didn’t say a word. It was the mother-in-law who spoke up.

“Egu—thanks be! Young lady, you are so sweet.” I could tell she meant it. And could see the passengers nearby were impressed. Well done! I told myself.

If it was another day, no way would I have done it. Why would I want to stop the bus? And to think I’d fetch someone a damn clack-clacker. Her crying wouldn’t have changed my mind, not even a tantrum. Not even if she’d clutched my arm and pleaded. In that case I would have snapped at her, Don’t want to deal with it! and followed up by pouting at her and mumbling, loud enough for her to hear, An outing . . . this is your idea of a damn outing? And I’m supposed to bend over backward for you? Why don’t you take your outing money, buy some laundry soap, and scrub that dirty neck of yours? Hmph!

So far, so good—my morning pledge was holding up, and not just to the young woman with the geta. I didn’t turn away any of the basket-head peddlers, not a single one. And I didn’t double-punch anyone’s ticket because of an oversized basket. I tried to accommodate everyone, and if someone with an oversized load volunteered the extra payment, I waved her off. And it was nice to see the thankful faces of people who were probably thinking, She made my day.

But . . . do you suppose they made any effort to meet my kindness with kindness of their own? On the contrary, I could tell they saw me as gullible, someone they could string along, and instead of goodwill, it was ill will they had in mind. It wouldn’t be long before some guy got on at Kwangnaru, played dumb and didn’t pay a fare, and then around Sŏngdong he’d say, “Gimme a ticket for Wangshimi—I got on at Togyo,” and hold out a ten-chŏn coin. I’d try nicely to get him to ’fess up, he wouldn’t go for it, and finally I’d have to bark at him, “What gives, mister? Come on,” and that’s the only way he’d get the point. An ass like that really deserves a rap on the head.

Little by little I got irritated. How can a person be kind and gentle with human trash like that? The hostility bubbled up inside me.

Back at the East Gate, before my next departure I was in the waiting room and saw a Kwangnaru bus pull in. While everybody was getting off, a guy in a shabby suit waltzed out into the lot like he owned the place—this was before ticket sales had begun—and he headed for the bus. Figured he’d grab himself a seat ahead of time and get nice and comfy. This was around the time I was really getting aggravated.

I followed him out and said, “Excuse me, kind sir?” I managed to be polite in spite of myself.

The guy turned around with an inquiring expression. “Where are you going?”

“I’m getting on the bus—what do you think?” “Boarding hasn’t started yet!”

“I have a return ticket!”

The guy was throwing a fit, and I could hear myself getting louder too: “A return ticket doesn’t give you the right to get on before the other passengers!”

“What!”

“Get mad all you want, it’s not going to get you anywhere. All the other passengers are waiting in line. What do you think you’re doing, trying to make things easy for yourself? Don’t you have any shame?”

“How dare you treat a passenger like this!”

“If you want to be treated well, then you shouldn’t step out of line like that!”

“What kind of nonsense is this, you little . . . ?”

He was about to strangle me, I could see it in his eyes, but the other girls stepped in and nothing came of it. But my insides were churning.

The strange thing is, when I get my dander up like this, none of the passengers looks decent to me. Doesn’t matter if there are ten or a hundred of them, male or female, young or old, all of the passengers on my Kwangjang line have crooked faces, faces wearing a permanent scowl, only one eye, pockmarks, twisted lips—in short, they’re the most ugly and threatening people, no manners or compassion, no kindness or etiquette, pathetic sons of bitches who don’t come close to being civilized.

And then on the return trip, we stopped at Sŏngdong. The bus was still packed to the brim, and as always there were a bunch of vendor women waiting, and they all tried to push their way on with their bulky baskets. The woman at the very front happened to make eye contact with me, and she broke out in a fake laugh and said in a treacly voice,

“Let me on, I’ll pay extra for my basket.”

If she hadn’t said anything, all would have been well, but when I saw that sly smile and heard the syrupy words, I barked at her, “No!” and then pushed her and her basket out, closed the door, and hit the button for departure.

The bus took off and the basket came off the woman’s head and ended up flipped over on the ground. In spite of myself, I looked back—and saw the eyes of that woman as she stood there gaping forlornly at the tail end of the bus. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a look so sad and despairing. I felt a surge of emotion in my chest and my eyes teared up. I resisted the urge to plop down and start bawling, and when we arrived at Wangshimni I was still not myself.

Yagŏp shinmun, June 18, 25, 1960

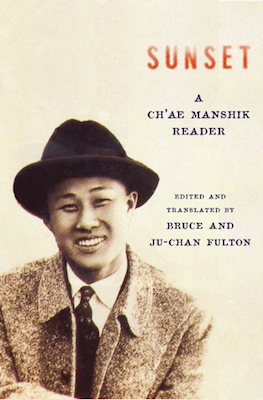

Excerpted from SUNSET: A CH’AE MANSHIK READER by Ch’ae Manshik. Edited and translated by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton. Translation Copyright (c) 2017 Columbia University Press. Used by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.