Andy Warhol’s Superstars and the Invention of Downtown New York

On a Modern Master of Surfaces and the Entourage He Created

Andy Warhol was among the first artists to uphold a kind of lifestyle as art that is now firmly ingrained in us during the age of Instagram filters and Snapchat stories. Before Warhol, artists of renown like Pablo Picasso and Jackson Pollock were hallowed names in the art world, but few outside the elites could probably identify their faces in a crowd. Warhol morphed into more than a successful aesthete, becoming an emblem to adorn bags, mugs, and other overpriced museum tchotchkes. Himself a stargazer who fussed over stars ranging from Truman Capote to Marilyn Monroe, Warhol knew the substance of the shining iconicity he was pursuing.

His reach extends to the actual bodies of our common idols. Old Lady Gaga pal Brendan Jay Sullivan recalled a moment of deep career flux for her while working for Interscope but not yet signed with the label. He recalled, “She told me she wanted to go and start over and get a nose job and be pretty and be a pop star. And the only way I could talk her out of it was I told her she needed to go to the Met and see this Warhol painting. It’s called Before and After. And it’s the image of a rhinoplasty. From then on I never heard anything else about cosmetic surgery and I heard only things about Warhol. I think maybe she connected to him in a new way.”

Warhol’s obsession with the surface appearance of things—the link between image and identity—was complicated. A Factory figure like the late Ultra Violet squeezed every last drop of fame from her proximity to Warhol, although her memoir offered a somber verdict: “This was a man who believed in nothing and had emotional involvements with no one, who was driven to find his identity in the mirror of the press, then came to believe that reality existed only in what was recorded, photographed, or transcribed.” Through this fixation, he became the font of an aesthetic sensibility still coursing through our cultural sinews.

Warhol gave his coterie a downtown space where the likeminded fame monsters could dream big dreams of being Up There. As Jonas Mekas told Stephen Koch, “Andy admired all the stars, so to please all those sad desperate souls that came into the Factory, Andy called them ‘Superstars.’” The disco names of Warhol’s claqueurs became sexy sobriquets for the sidewalks that became their stages. He sanctified their unabashed hunger for fame. It became art.

And so the Factory’s output was personas as well as paintings, a social scene alongside silk screens. The creation of his micro-star system evolved with Warhol always as the center of gravity. He fed their ambitions while they nurtured his aura. As René Ricard declared in the Jean Stein collection about Warhol’s greatest Factory star, “Edie [Sedgwick] brought Andy out. She turned him on to the real world. He’d been in the demimonde. He was an arriviste. And Edie legitimized him, didn’t she? He never went to those parties before she took him. He’d be the first to admit it.”

While Steve Watson, Stephen Koch, Victor Bockris, and others have thoroughly researched the Superstars’ lives, my goal here is to understand their place in downtown mythmaking. Joe Dallesandro biographer Michael Ferguson offered an apt summary:

Andy Warhol was bestowing delusions of grandeur. His Superstars were a camp celebration of America’s surrogate royalty, its Cult of Celebrity—which was infinitesimal compared to the grotesque worship we see today. Who was to say that his down-and-dirty, glam-trashy stars weren’t precisely what he called them and no less worthy of their titles in superlative than those endowed by Hollywood?

Claiming the title of “superstar” meant calling themselves now what they hoped to become in the future, a mantra later amplified by Gaga’s maxim about “the spiritual hologram of who we perceive ourselves to be.” Club kid king Michael Alig understood the power of this preemptive performance when he crowned his boyfriend Keoki a “Superstar DJ.” As Keoki told me, “Michael was like, ‘You should call yourself Superstar DJ.’ And I thought, ‘Well that’s kind of weird.’ He was like, ‘Why not? You just gotta say it and it’ll be true.’”

The key to understanding the power of Warhol’s downtown brand is this entourage of people feeding off his aura and in turn imbuing his public persona with their spark. Attentive to the heavenly stars’ impact on us, ex-club kid Sophia Lamar observed, “[Warhol] was Leo. Sometimes in Leo with that personality [they] create that kingdom where they are king because outside that kingdom they are nobody. So he was a very talented and creative artist. And he created that kingdom, that small kingdom, where he manipulated people and played with them.”

Today there’s sometimes debate as to who really qualifies as a Warhol Superstar, a term whose origin Steven Watson locates around 1965, mainly in the Cinemaroc work of filmmaker Jack Smith, from whom Warhol also “borrowed” a great deal. In Edie: American Girl, René Ricard claimed that the term was invented by Factory figure Chuck Wein and noted that he had only come upon the term once before in a 1930s fan magazine. However the moniker emerged, it reflected the crew’s clear emulation of Hollywood stars like Marilyn Monroe, Liz Taylor, Lana Turner, Kim Novak, Hedy Lamarr, and others. It was both a reperformance of these American icons and a staging of what they wished to be: to break out of downtown and become true household names living luxe lives.

A popular listing exists on warholstars.org, a valuable resource for fans, scholars, and journalists. The site is run by Gary Comenas, an independent researcher in London who has meticulously documented key aspects of Warholia. Although his site lists three-dozen stars, here I mainly refer to the ones who haven’t fallen down the memory hole and are still widely known and referenced in downtown New York today. Some of the most fabulous Factory stars, like Mary Woronov, International Velvet, and Viva, are no longer on the East Coast.

Warhol selected, but sometimes the Superstars recruited. The late Holly Woodlawn’s anointing started when her pals Jackie Curtis and Candy Darling appeared in Flesh and invited her to a Factory party at 33 Union Square West to be presented to their hero patron. “He’ll make us the three goddesses of the screen,” they promised. When Holly and I spoke about this, she was adamant about her reluctance to be absorbed into a scene with which she’ll forever be associated. She told me, “I never wanted to be [a Superstar], believe it or not, I did not want to be.” At the party she remembered spotting Warhol wearing “the cheapest white yak hair wig I have ever seen in my life.” He walked over. “You’re so glamorous,” Warhol declared. “I thought he was out of his mind,” she sniffed.

__________________________________

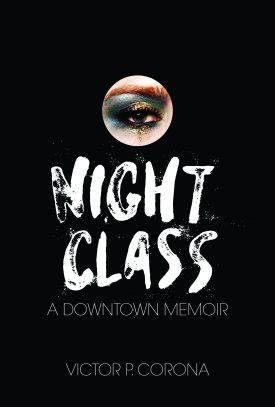

From Night Class: A Downtown Memoir, by Victor P. Corona, courtesy Soft Skull. Copyright Victor P. Corona 2017.