Four sentences that I wrote years ago keep coming back to me. I am still not certain that I understand these sentences. Part of me wants to nail them down, while another fears that by doing so I will snuff out a meaning that can’t be told in words—or, worse yet, that the very attempt to fathom their meaning might allow it to go into deeper hiding still. It’s almost as though these four sentences don’t want me, their author, to know what I was trying to say with them. I gave them the words, but their meaning doesn’t belong to me.

I wrote them when attempting to understand what lay at the source of that strange strain of nostalgia hovering over almost everything I’ve written. Because I was born in Egypt and, like so many Jews living in Egypt, was expelled, at the age of fourteen, it seemed natural that my nostalgia should have roots in Egypt. The trouble is that as an adolescent living in Egypt in what had become an anti-Semitic police state, I grew to hate Egypt and couldn’t wait to leave and land in Europe, preferably in France, since my mother tongue was French and our family was strongly attached to what we believed was our French culture.

Ironically, however, letters from friends and relatives who had already settled abroad kept reminding those of us who continued to expect to leave Alexandria in the near future that the worst thing about France or Italy or England or Switzerland was that everyone who had left Egypt suffered terrible pangs of nostalgia for their birthplace, which had been their home once but was clearly no longer their homeland. Those of us who still lived in Alexandria expected to be afflicted with nostalgia, and if we spoke about our anticipated nostalgia frequently enough, it was perhaps because evoking this looming nostalgia was our way of immunizing ourselves against it before it sprang on us in Europe. We practiced nostalgia, looking for things and places that would unavoidably remind us of the Alexandria we were about to lose. We were, in a sense, already incubating nostalgia for a place some of us, particularly the young, did not love and couldn’t wait to leave behind.

We were behaving like couples who are constantly reminding themselves of their impending divorce so as not to be surprised when indeed it finally does occur and leaves them feeling strangely homesick for a life both know was intolerable.

But because we were also superstitious, practicing nostalgia was, in addition, a devious way of hoping to be granted an unanticipated reprieve from the looming expulsion of all Egyptian Jewry, precisely by pretending we were thoroughly convinced it was fated to happen soon and that indeed we wanted it to happen, even at the price of this nostalgia that was bound to strike us once we were in Europe. Perhaps all of us, young and old, feared Europe and needed at least one more year to get used to our eagerly awaited exodus.

But once in France I soon realized that it was not the friendly and welcoming France I had dreamed of in Egypt. That particular France had been, after all, merely a myth that allowed us to live with the loss of Egypt. Yet, three years later, once I left France and moved to the United States, the old, imagined, dreamed-of France suddenly rose up from its ashes, and nowadays, as an American citizen living in New York, I look back and catch myself longing once more for a France that never existed and couldn’t exist but is still out there, somewhere in the transit between Alexandria and Paris and New York, though I can’t quite put my finger on its location, because it has no location. It is a fantasy France, and fantasies—anticipated, imagined, or remembered—don’t necessarily disappear simply because they are unreal. One can, in fact, coddle one’s fantasies, though recollected fantasies are no less lodged in the past than are events that truly happened in that past.

The only Alexandria I seemed to care about was the one I believed my father and grandparents had known. It was a sepia-toned city, and it stirred my imagination with memories that couldn’t have been mine but that harked back to a time when the city I was losing forever was home to many in my family. I longed for this old Alexandria of two generations before mine, knowing that it had probably never existed the way I pictured it, while the Alexandria that I knew was, well, just real. If only I could travel from our time zone to the other bank and recover this Alexandria that seemed to have existed once.

I was, in more ways than one, already homesick for Alexandria in Alexandria.

Today I don’t know if I miss Alexandria at all. I may miss my grandmother’s apartment, where everyone in the family spent weeks packing and talking about our eventual move to Rome and then Paris, where most members of the family had already settled. I remember the arrival of suitcases, and more suitcases, and many more suitcases still, all piling up in one of the large living rooms. I remember the smell of leather permeating every room in my grandmother’s home while, ironically enough, I was reading A Tale of Two Cities. I miss these days because, with our imminent departure, my parents had taken me out of school, so that I was free to do as I pleased on what seemed like an improvised holiday, while the comings and goings of servants helping with the packing gave our home the air of being set up for a large banquet.

I miss these days perhaps because we were no longer quite in Egypt but not in France either. It is the transitional period I miss—days when I was already looking ahead to a Europe I was reluctant to admit I feared, all the while not quite able to believe that soon, by Christmas, France would be mine to touch. I miss the late afternoons and early evenings when everyone in the family would materialize for dinner, perhaps because we needed to huddle and draw courage and solidarity together before facing expulsion and exile. These were the days when I was beginning to feel a certain kind of longing that no one had explained to me just yet but that I knew was not so distantly related to sex, which, in my mind, I was confusing with the longing for France.

When I look back to my last months in Alexandria, what I long for is not Alexandria; what I long for when I look back is to revisit that moment when, as an adolescent stuck in Egypt, I dreamed of another life across the Mediterranean and was persuaded its name was France. That moment happened when, on a warm spring day in Alexandria with our windows open, my aunt and I leaned on the sill and stared out at the sea, and she said that the view reminded her of her home in Paris where, if you leaned out a bit from her window, you’d catch a view of the Seine. Yes, I was in Alexandria at that moment, but everything about me was already in Paris, staring at a slice of the Seine.

But here is the surprise. I didn’t just dream of Paris at the time; I dreamed of a Paris where, on a not so distant day, I would stand watching the Seine and nostalgically recall that evening in Alexandria where, with my aunt, I had imagined the Seine.

One can, in fact, coddle one’s fantasies, though recollected fantasies are no less lodged in the past than are events that truly happened in that past.So here are the four sentences that have been giving me so much trouble:

When I remember Alexandria, it’s not only Alexandria I remember. When I remember Alexandria, I remember a place from which I liked to imagine being already elsewhere. To remember Alexandria without remembering myself longing for Paris in Alexandria is to remember wrongly. Being in Egypt was an endless process of pretending I was already out of Egypt.

I was like the Marranos of early modern Spain, who were Jews who converted to Christianity to avoid persecution but who continued to practice Judaism in secret, not realizing that, with the passing of time and generations later, they would ultimately confuse both faiths and no longer know which of the two was truly theirs. Their anticipated return to Judaism once the crisis was behind them never occurred, but their adherence to Christianity was no less an illusion. I was nursing one sense of myself in Alexandria and cradling another in Paris, all the while anticipating that a third would be looking back to the one I’d left behind once I was settled across the shore.

I was toying with a might-have-been that hadn’t happened yet but wasn’t unreal for not happening and might still happen, though I feared it never would and sometimes wished it wouldn’t happen just yet.

Let me repeat this sentence, the substance of which will appear many times in this volume: I was toying with a might-have-been that hadn’t happened yet but wasn’t unreal for not happening and might still happen, though I feared it never would and sometimes wished it wouldn’t happen just yet.

This, like a dead star, is the secret partner of the four sentences that have been giving me so much trouble. It disrupts all verbal tenses, moods, and aspects and seeks out a tense that does not conform to our sense of time. Linguists call this the irrealis mood.

Mine is not simply a longing for the past. It is a longing for a time in the past when I wasn’t just projecting onto Europe an imaginary future; what I long for is the memory of those last days in Alexandria when I was already anticipating looking back from Europe on the very Alexandria that I couldn’t wait to lose. I long for myself looking out to the self I am today.

Who was I in those days, what were my thoughts, what did I fear, and how was I torn? Was I already trying to convey to Europe pieces of my Alexandrian identity that I feared I was about to shed for good? Or was I trying to graft my imagined European identity onto the one I was about to leave behind?

This circuitous traffic that aims to preserve something we know we are about to lose lies at the essence of the irrealis identity. Whatever it is I am trying to preserve may not be entirely real, but it isn’t altogether false. If I am still today creating circuitous rendezvous with myself, it’s because I keep looking for some sort of terra firma under my feet; I have no set anything, no rooted spot in time or place, no anchor, and, like the word almost, which I use all too often, I have no boundaries between yes and no, night and day, always and never. Irrealis moods know no boundaries between what is and what isn’t, between what happened and what won’t. In more ways than one, the essays about the artists, writers, and great minds gathered in this volume may have nothing to do with who I am, or who they were, and my reading of them may be entirely erroneous. But I misread them the better to read myself.

I was toying with a might-have-been that hadn’t happened yet but wasn’t unreal for not happening and might still happen, though I feared it never would and sometimes wished it wouldn’t happen just yet.*

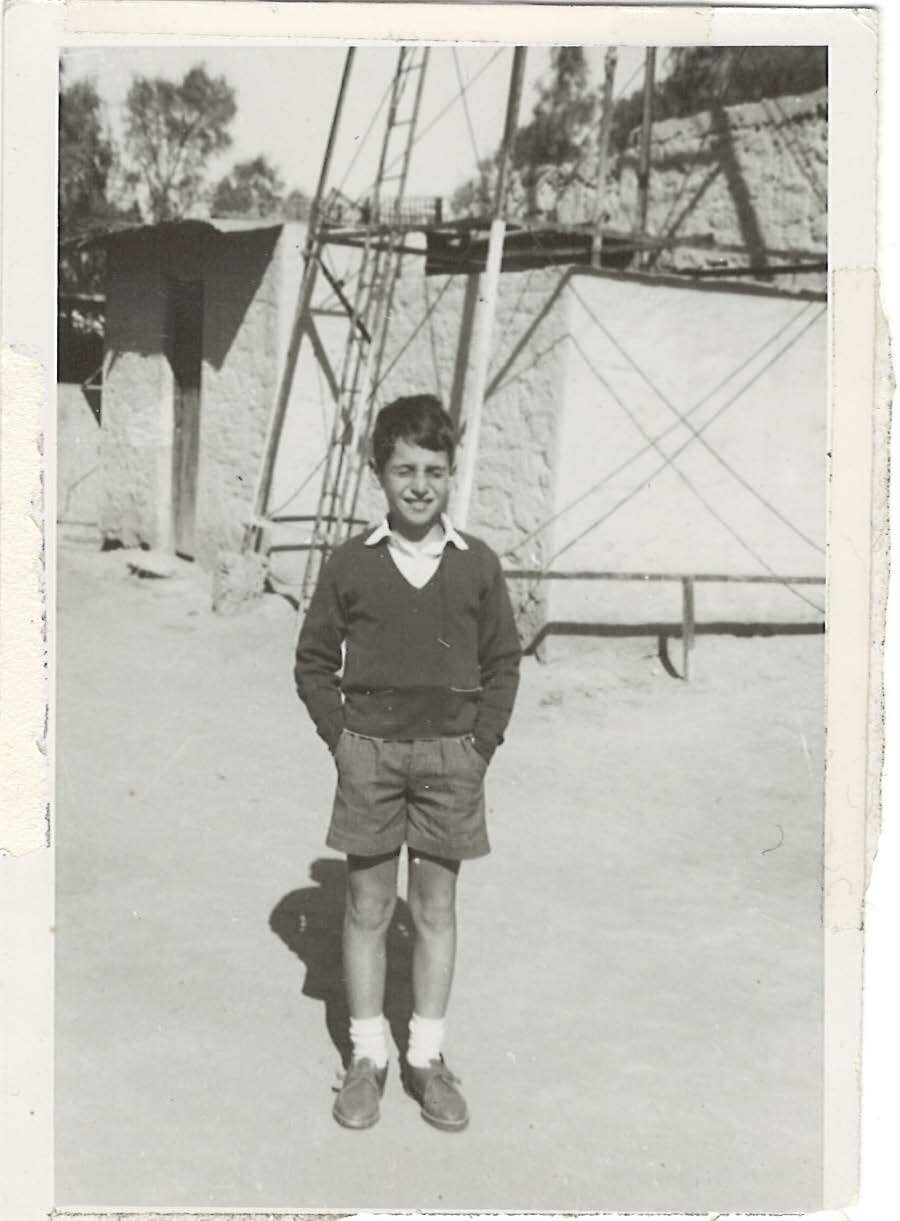

A picture that my father took of me is my last picture in Egypt. I was scarcely fourteen. In the picture I am squinting and trying to keep my eyes open—the sun is in my face—and I’m smiling rather self-consciously, because my father is chiding me and telling me to stand up straight for once, while all I’m probably thinking is that I hate this desert oasis about twenty miles from Alexandria and can’t wait to be back and heading to the movies. I must have known that this was the last time I’d ever see this oasis in my life. There is no other picture of me in Egypt after this one.

To me it represents the last instance of who I was two to three weeks before leaving Egypt. As I stand there in my typically reluctant, undecided posture with both my hands in my pockets, I have no idea what we’re doing in this desert outpost or why I’m letting my father take my picture.

I can tell my father is not pleased with me. I’m trying to look like the person he thinks I should be—Stand straight, don’t wince, look decisive. But this is not me. Yet now that I look at the picture, this is who I was that day. I, trying to be someone else or caught ever so awkwardly between who I didn’t like being and who I was being asked to be.

When I look at the black-and-white photo, I feel for that boy of almost six decades ago. What happened to him? Whatever did he end up becoming?

He isn’t gone. Perhaps I wish he were gone. I’ve been looking for you, he says. I’m always looking for you. But I never speak to him; I seldom ever think of him. Yet now that he’s spoken up, I’ve been looking for you too, I say, almost by way of a concession, as if I’m not sure I even mean what I’ve just said.

And then it hits me: something happened to the person I was back then in that picture, to the person staring at the father who is ordering him to stand up straight, adding, as he so frequently did, a cutting “for once,” as if to make certain his criticism landed where it hurt. And the more I look at the boy in the picture, the more I begin to realize that something separates me from the person I might have become had nothing changed, had I never left, had I had a different father or been allowed to stay behind and become who I was meant to be, or even wanted to be. It’s the person I was meant to be or could have become that continues to rankle in my mind, because it’s right there in the picture, but ever so hidden.

It is a longing for a time in the past when I wasn’t just projecting onto Europe an imaginary future; what I long for is the memory of those last days in Alexandria when I was already anticipating looking back from Europe on the very Alexandria that I couldn’t wait to lose.What happened to the person I was actually working on becoming but didn’t know I was about to become, because one never quite knows that one is indeed working on becoming anyone? I look at the black-and-white picture of someone over there and am tempted to say, This is still me. But it’s not. I didn’t stay me.

I look at the picture of the boy posing for his father with the sun in his face, and he looks at me and asks, What have you done to me? I look at him, and I ask myself: What in God’s name have I done with my life? Who is this me who got cut off and never became me, the way I cut him off and never became him?

He has no words of comfort. I stayed behind; you left, he says. You abandoned me; you abandoned who you were. I stayed behind, but you left.

I have no answers for his questions: Why didn’t you take me with you? Why did you give up so fast?

I want to ask him who of us two is real, and who is not.

But I know what his answer will be. Neither of us is.

*

When I was last in Nervi, I took a picture of Via Marco Sala, the main, meandering street that connects the small town of Bogliasco to Nervi, south of Genoa. Using my iPhone, I took the picture at dusk, partly because there was something about dusk on an empty, curved road I liked, and partly because there was a strange glow on the pavement. I waited for a car to disappear before taking the picture. Perhaps I wanted the scene to exist outside of time, with no real indication of where, when, or in which decade the picture was taken. Then I posted the picture on Facebook.

Someone liked that I had mentioned Eugène Atget and right away took my colored image and turned it into black-and-white, thus giving the photo a pale, early-twentieth-century look. I hadn’t asked anyone to do this, but obviously it was implied somewhere, or someone simply inferred my undisclosed wish and decided to act on it. Someone else then liked what this person had done to my picture and decided to do one better: this time it looked as though the photo were taken in 1910, or 1900, and had acquired now a faint sepia quality. This person had interpreted the original purpose of the picture and given it to me as I had originally desired it. I wanted a 1910 picture of Nervi but didn’t know that I was, in my own way, trying to turn back the clock. I got another Facebook friend to reproduce a Doisneau Nervi; another was kind enough to produce a Brassaï Nervi.

Irrealis moods know no boundaries between what is and what isn’t, between what happened and what won’t.I like images of vieux Paris. They bring back an old world that disappeared and that I am fully aware may have been quite different from the one photographers like Atget and Brassa wanted to seize on film. Photographs capture buildings and streets, not people’s lives, not their strident voices, their bickering catcalls, their smell, or the stench of the gutters running down filthy streets. Proust: the scents, the sounds, the moods, the weather . . .

What I should have suspected—but didn’t know—was that I was taking a picture not so much of a Nervi stripped of all time markers; I was taking a picture of Alexandria as I continue to imagine it at the time when my grandparents had moved there, more than a century ago.

The picture altered on Facebook turned out to reveal the subliminal reason I had taken it in the first place; unbeknownst to me, it reminded me of a mythical Alexandria that I seemed to recall but was no longer sure I’d ever gotten to know. What Facebook had returned to me was an irrealis Alexandria via an imitation Paris imitating an unreal Alexandria in a small town in Italy called Nervi.

I was no longer the young boy staring out the window with my aunt at an imagined Paris. I was, as I’d predicted even back then, trying to catch a glimpse of the boy staring out to me, except that I felt no more real than he was then. I would never know who he was, locked in Alexandria still staring out to me, just as he will never know who I was or what I was doing that evening on Via Marco Sala. We were two souls longing to connect from across opposite banks.

All I knew after I put away my iPhone was that I would eventually have to go back to Alexandria and see for myself that I hadn’t invented what I’d discovered on Via Marco Sala. But going back would never prove anything, just as knowing that wouldn’t prove anything either.

__________________________________

From Homo Irrealis: Essays by André Aciman. Excerpted with the permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2021 by André Aciman.