An Unequal Partnership: On the Marriage of Kingsley Amis and Jane Howard

Carmela Ciuraru Explores What Literary Wives Are Forced to Sacrifice for Their Husbands' Success

Kingsley Amis’s relationship with Elizabeth Jane Howard, known as Jane, was a stabilizing force, at least for him. Both were ambitious writers, but only one could achieve success. The other was expected to lend unconditional support and forsake all personal desires. If Jane could not tolerate in herself the ruthlessness often required in fully realizing one’s talent, Kingsley did not give it a second thought. He pursued his vocation in a headlong way, with no regard to the fallout on those closest to him.

Even though he had been seduced by a sexy novelist, what he really needed, day to day, was an attentive housewife and caregiver. Theirs was a hierarchical relationship in which Kingsley was always on top, rather than the equal partnership Jane had hoped for. He was encouraging and supportive about her work—but only to a point. She tried not to mind. After he read her 1959 novel, The Sea Change, Kingsley praised it in his own way. “That’s a very good novel indeed,” he said. “I am so relieved. I was afraid you wouldn’t be any good.”

Jane’s autonomy was tolerated so long as it did not interfere with her husband’s needs, yet it almost always did. Any effort to speak up fell on deaf ears, but Jane could convince herself that she felt content if she had Kingsley’s affection and approval. She depended on it. When he was feeling cheerful, he would look at his wife adoringly and say, “I have such a lovely life with you!” All was right with the world.

Jane’s autonomy was tolerated so long as it did not interfere with her husband’s needs, yet it almost always did.

Jane was well acquainted with men behaving badly, especially as she tried to assert her position among London’s male-dominated literary set. Once, while conducting what would be Evelyn Waugh’s final broadcast interview—for the BBC, in 1964—Jane endured his belittling comments (“Ah, Miss Howard—and have you had anything to do with literature?”) and dotty remarks to the camera crew: “When is Miss Howard going to take off all her clothes?” She was fond enough of men to overlook their more beastly moments, and for Kingsley she seemed to retain an infinite store of patience and forgiveness.

In the spring of 1965, Kingsley and Jane married at Marylebone Town Hall in London. The fawning media attention was difficult for Kingsley’s ex-wife, Hilary (known as Hilly); she admitted later that she was still in love with the man who had left her and their three children.

Although Jane’s marriage was off to a happy start, Kingsley’s uxorious feelings toward her were not to last. For a while, though, they made a glamorous, picture-perfect power couple and were much in demand socially. In a 1963 letter, Kingsley had cheekily written to Jane that they should announce to the world “THAT THEY ARE THE MOST ATTRACTIVE, INTELLIGENT, FUNNY, SOPHISTICATED AND MUTUALLY SUITED PAIR SINCE THE RENAISSANCE.”

They bought a 30-room Georgian house with eight bedrooms, a detached cottage, and a barn. The secluded property included several acres, with a beautiful, sloping garden, a meadow, and cedar woods. They could barely afford the house but were overjoyed to have it. Although they loved each other’s company, things were harmonious largely because Jane accommodated Kingsley’s wishes day and night. The division of labor was clear: she took care of everything, while his days were freed up for creative work. “He got up and wrote,” Jane recalled. “Then he ate lunch, had a walk or sleep, and then he wrote again.” It was an idyllic existence—for him. As a friend put it: “Jane cooked and Kingsley drank.”

She had to take on not only traditionally “female” domestic duties, but “male” responsibilities such as changing light bulbs and fuses around the house. She scheduled her husband’s medical appointments. She handled the household budget—he couldn’t be bothered, even though their finances were always in a precarious state—and served as the family’s chauffeur. Kingsley refused to drive and was afraid to travel on the Underground. (He said that he cured himself of this fear by never riding the tube again.) She was his part-time secretary. She was not to nag him about his drinking, which, among other things, he considered an essential social lubricant. Alcohol, for him, was inseparable from pleasure.

She wrote his thank-you notes. Because he hated “boring” dark socks, she knitted him multiple pairs in gorgeous, striking colors. She met with their accountants and lawyers. She tended to her husband’s panic attacks and phobias, including a terror of being alone in the house at night. His children (Martin, Philip, and Sally) often took it upon themselves to “Dadsit” whenever Jane was out after dark.

She loved to cook, did all the grocery shopping, and carefully prepared dinner each night. But Kingsley could behave like a petulant toddler at mealtime. Jane also decorated, furnished, and cleaned the house, while Kingsley’s household duties were limited to mixing and serving drinks. Jane got out of ironing only by claiming she didn’t know how to do it—a lie—but nothing else was deemed outside her purview. She was constantly, and understandably, exhausted and after dinner she would often fall asleep, upright in a chair.

The division of labor was clear: she took care of everything, while his days were freed up for creative work.

Years later, in a letter to his friend Philip Larkin, Kingsley would mock Jane for the disparaging things she had said about him in an interview following their breakup in 1983: “[S]he said I stifled her creative talent by making her run the house,” he wrote. “Yes, she never did anything but cook, and never cooked except when we had people, about twice a month.” (This was not true.) After the word “cooked,” he inserted an asterisk, and at the bottom of the letter he had written the phrase “elaborately but not very well.”

It wasn’t enough that Jane had to care for her own family, and that Kingsley was so unappreciative of all she had to manage. He insisted upon entertaining weekend houseguests, so setting the dinner table for twelve or more was not uncommon. (One Christmas, there were twenty-five people.) Kingsley loved being the center of attention, and he was good at it. He would drink, crack jokes, talk politics, and tell stories late into the night. “I think it was wonderful for everyone but Jane,” recalled a friend. Visitors to the Amis-Howard home included John Betjeman, Pat Kavanagh, John Bayley, Iris Murdoch, and Elizabeth Bowen.

Cecil Day-Lewis, suffering from late-stage cancer, came to live with Kingsley and Jane. He died in their home in 1972, at sixty-eight, and wrote his final poem there. Years earlier, Jane and Day-Lewis had a brief affair. He was married to his second wife, Jill Balcon, who was Jane’s best friend and confidante. (When Day-Lewis began his relationship with Balcon, he was still married to his first wife, Constance—and already had another mistress on the side.) Jane once described him as “an “exceptionally beautiful man, with a marvelous forehead creased and mapped like the tributaries of a river.” She felt intensely guilty about having betrayed Jill, and managed, eventually, to reconcile with her.

At home, by so often acquiescing in silence to please Kingsley, Jane recognized that she was enabling his unrelenting demands. “It’s true to say that writers are selfish people,” she once said. “All artists are really. But it’s not quite enough of an excuse.” Any distress she felt was of no consequence to her crapulous husband. He was rigorous in his work, careful never to drink much until he had finished writing for the day. That meant that he was very drunk in the evenings, when Jane hoped to spend time with him. “Kingsley felt women were for fucking and cooking,” Jane once said. “He stopped wanting to fuck because if you get really very drunk all the time you stop being able to do it.” As it happens, the bitter protagonist of Kingsley’s 1978 novel, Jake’s Thing, is a late-middle-aged Oxford don who has lost his libido and despises women.

In many of Kingsley’s novels, women prove troublesome. The narrator’s best friend in the bilious Stanley and the Women is shocked to learn that “only” twenty-five percent of violent crime in England and Wales is the result of husbands assaulting their wives. “You’d expect it to be more like eighty percent,” he says. Kingsley, feeling vindictive and bereft, published this novel the year after he and Jane divorced. His misogynist streak was evident in interviews, too: “It’s nice to have a pretty girl with large breasts,” he said in 1973, “rather than some fearful woman who’s going to talk to you about Ezra Pound and hasn’t got large breasts and probably doesn’t wash much.”

In her writing, Jane often saw nothing but paths toward failure.

Jane always marveled at her husband’s intense discipline in his work. Something was in the midst of production at all times. However extreme his hangover, however foul his mood, he ate breakfast each morning and got straight to work. As Martin later described it, Kingsley was a “grinder,” trudging over to his desk no matter what. He also noted, with admiration, that his perfectionist father was adept at problem-solving when stuck:

My father described a process in which, as it were, he had to take himself gently but firmly by the hand and say, Now all right, calm down. What is it that’s worrying you? The dialogue will go: Well, it’s the first page, actually. What is it about the first page? He might say, The first sentence. And he realized that it was only a little thing that was holding him up. Actually, my father, I think, sat down and wrote what he considered to be the final version straightaway, because he said there’s no point in putting down a sentence if you’re not going to stand by it.

Jane, though, often felt too worn down by fatigue, anxiety, and insecurity to write. “He was incredibly disciplined about his work and was a marvelous example for me,” Jane once said of Kingsley, “although I didn’t have the same time to do it.” Her days were a series of missed opportunities. (“Writing is a fraught activity for anyone, of course, male or female,” Janet Malcolm wrote in The Silent Woman, “but women writers seem to have to take stronger measures, make more peculiar psychic arrangements, than men to activate their imaginations.”)

Jane began to retreat. Her solace was gardening: it was private, all hers. Even though she felt guilty about indulging this passion—so much was expected of her—she carried on doing it. Gardening was easier and more pleasurable than writing. She could make something derelict grow, and with satisfying results. In her writing, Jane often saw nothing but paths toward failure. She was terrified of the blank page.

Kingsley, who had broken ties with his previous agent, Curtis Brown, signed up with both Jane’s agent, A.D. Peters, and her publisher, Jonathan Cape—leaving her feeling cast aside in favor of the bigger star. In the years she spent with Kingsley, her self-image sank ever lower. Once, when a therapist asked what Jane liked about herself, all she could come up with was to say that she considered herself “reliable.” In contrast, Kingsley’s amour propre was unwavering. He was neither haunted by guilt, nor prone to reprimanding himself. He was beyond reproach and would not be challenged. A former acquaintance recalled that when someone once admonished Kingsley for behaving rudely, he replied, “Fuck off. No, fuck off a lot.”

__________________________________

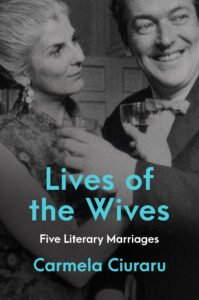

Excerpted from Lives of the Wives: Five Literary Marriages by Carmela Ciuraru. Copyright © 2023. Available from Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Carmela Ciuraru

Carmela Ciuraru is the author of Lives of the Wives (Harper), as well as the critically acclaimed book Nom de Plume: A (Secret) History of Pseudonyms (Harper). Her anthologies include First Loves: Poets Introduce the Essential Poems That Captivated and Inspired Them and several volumes in the Everyman’s Library Pocket Poets series. She has been interviewed on The Today Show and by newspapers and radio stations internationally.