An Open Letter to My Dog: I Couldn't Have Written This Without You

Cinelle Barnes on How She Pushed Through a Trauma Memoir

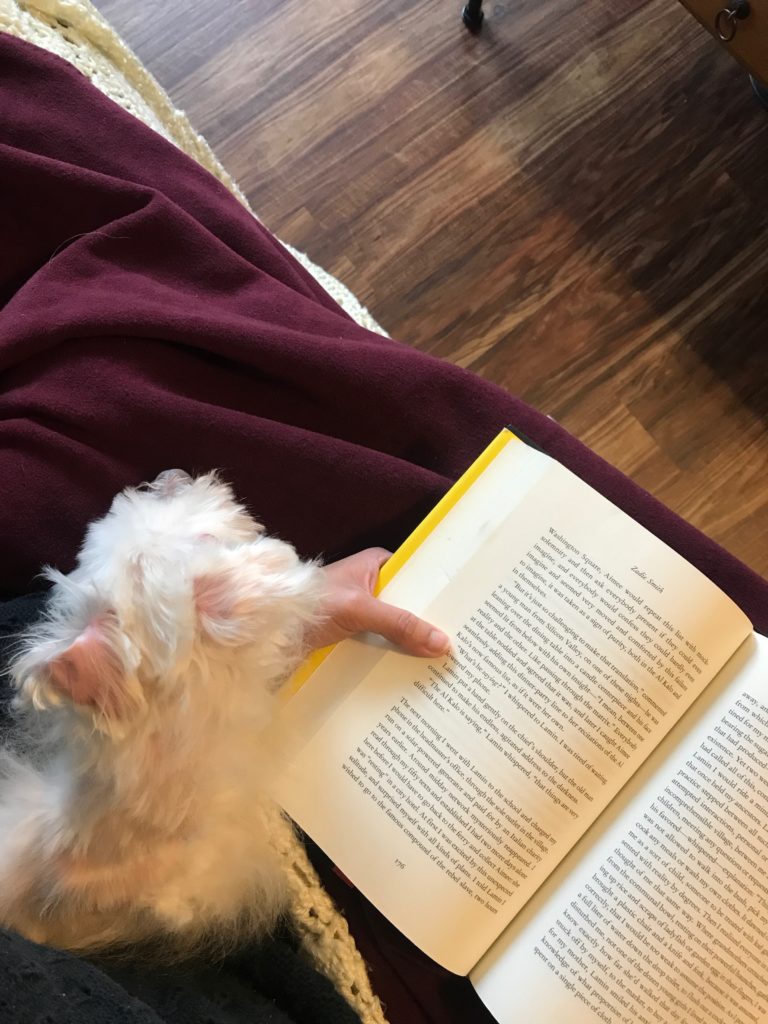

I’ve spent the past six years traveling through time, revisiting three decades through the portal of memoir. You sat on my lap as I ventured back to 2000, 1999, 1998, 1997, all the way to the year of my birth, 1986. You stretched between the armrests, your chin on my typing hand and your floppy ear on my wrist. When I started to cry, you turned around and placed your paws on my chest, and you licked away the tears rolling down my chin and neck. I only knew to stop, to click “Save” and “Exit,” when you whined because you sensed that my breathing pattern had shifted, my perspiration had increased, and my foot-tapping had hastened. My job was to remember. Yours was to make sure I was okay.

One year into this process, my daughter was born. We lived in isolation in a new city, and I had no family nearby to help. It was just you, me, and her in our clammy apartment while my husband was at work. She liked to fuss and had trouble sleeping, and only calmed down when she was rocked and held. I paced back and forth with her in my arms, swaying and jiggling to the beat of “Peace Like a River,” and we marked the carpet with twin tracks—yours and mine. You were always less than a foot away. When I changed her diaper, you stood by the pail as if ready to cushion her should she roll off the changing table. When I introduced solid foods, you sat at the base of her highchair with your snout pointing up, ready to catch bits of sweet potato or avocado. When she started to walk, you were her cheerleader. You pounced onto your front paws to tempt her to move, and as she toddled and fell and toddled and fell, you stayed in ready-set-go position, waiting for her to champion her new skill and make it to the finish line you’d fluffed and pilled from the carpet.

The next year, my husband suggested I take my writing seriously, meaning a course or a blog or some other structure that permitted me, forced me, to write for an audience. My daughter had begun to wean anyway, and she had developed an interest in places far beyond my lap and embrace—the kiddie pool, the sprinkler, the neighborhood slide and swing. He searched the internet and found a master of fine arts program I could do from home. When I applied and was granted a spot, naptime became homework time, and so did dinnertime and late nights. It was two years of essay packets, reading assignments, and very little real food. You ate what we ate, because I forgot to buy kibble, which meant all four of us had ramen or boxed mac ’n’ cheese.

My fondest memory from that time is of you and your sister laying parallel across my lap as she nursed and I wrote. She liked to twirl her fingers in my hair or yours as she fed, and she loved the warmth of your back against hers. She was a slow breastfeeder; it took her 40 minutes to get her fill. But I didn’t mind, as long as I could have those minutes to sit down and pen a few words or phrases on 3 by 5 notecards—the only way I could write while holding you both. Back then, I was writing to help myself feel better. The baby blues didn’t go away at week six, nor at month three, six, nine, as the nurse practitioner kept promising at every wellness check-up. Holding you and sister close, and writing, were the only things that relieved me of anxiety and grief.

*

Your birth name is Skye, because your fur is white and fluffy like a cloud. But sometimes we call you “mountain goat” or “Nubian ibex” because you find the most awkward, the most precarious, the most unjustifiable spots to perch on: the backrest to the futon, the recycling bin, your sister’s book bin, her stuffed animal bin, your father’s left shoe, his right shoe, my neck, and most consistently, the armrests of my writing chair. We call you “brother” because the only way I could free my arms of a crying baby or a whiny dog was to put you and her in the battery-operated swing, together. Side by side, both long and narrow, both under eight pounds, you two napped in the back-and-forth cradle that played a beeping version of “It’s A Small World.”

Nowadays we call you “old man” because of your graying nose, your whiskers and white beard, and the warts on your forehead, neck, and back. As you turn 14 (or 72 in toy dog years), you show signs of aging that I wish I could ignore. Cataracts, muscle atrophy, weight loss, an unwillingness to fetch. You don’t chase your sister around as much and no longer try to jump in the bath with her. On Christmas, you started dragging your right hind leg behind you, as if it weren’t attached to your body, as if it were just pine straw stuck to the matting on the base of your tail. You couldn’t get your legs over the crumples of wrapping paper on the floor. You couldn’t dash to where your sister was sitting, where she had opened your present, a squeaky toy taco. You crawled to me but couldn’t get your body up on my lap, so I cupped your back half and scooped you onto the crisscross of my legs.

The vet says it could be an old fracture that had healed wrong, or a severe case of arthritis. But he also says he can’t rule out bone cancer. So I give you Rimadyl for the pain and glucosamine for joint flexibility, and I time them as such: Rimadyl before I sit down to write, and glucosamine after I save a new draft of an essay or prose poem on trauma narratives, motherhood, or writing as healing. In between the two tablets, I cry sporadically and hold you up to my face to smell your dog breath, my daily dose of oxytocin. I whisper in your ear, “It’s not cancer, buddy. You’re going to live long. Long enough to see the book out in the world.” And now it is.

When journals and magazines ask how I wrote it, I tell them, “With a child dangling from my neck and a dog on my lap.” When they ask me what tools I use, any talismans I own, I reply “My dog is my talisman—I carry him with me wherever I go, sometimes in my jacket.” When they ask me how was I able to push through the painstaking work of writing a trauma memoir, I explain, “My dog licked my face when I cried. And he stayed close. And he loved me.”

My job is to remember. And without you, I’m not sure I’ll be okay. But you will still be every story I will ever write and have written. Because love is beyond time. While my craft relies on the absolutes of days, hours, and minutes, I know that it will only take remembering you to make time irrelevant. To make then, now. Then, again.

Cinelle Barnes

Cinelle Barnes is a creative non-fiction writer and educator from Manila, Philippines. She writes memoirs and personal essays on trauma, growing up in Southeast Asia, and on being a mother and immigrant in America. In 2014, she was nominated for the AWP Journal Intro Award for Creative Non-Fiction, and in 2015 received an MFA from Converse College. She was part of the inaugural Kundiman Creative Non-Fiction Intensive in New York City and will be attending the VONA/Voices workshop for political content writing at the University of Pennsylvania in summer 2017. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Literary Hub, Skirt!, West Of, Your Life Is A Trip, the Piccolo Spoleto Fiction Series, Itinerant Literate's StorySlam, and Hub City Press's online anthology, Multicultural Spartanburg. Her debut memoir, Monsoon Mansion, will be available through Amazon.com and independent booksellers in Spring 2018 (Little A).