An Ode to Harriet the Spy, the Art Monster of East End Avenue

Caroline Hagood on Louise Fitzhugh’s Ferocious and Wonderful Girl Flâneuse

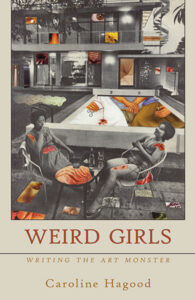

The concept of the art monster, the (historically male) wildly dedicated artist (enabled by his wife typing up his manuscripts and tending to his tots) is not a new concept, but it was officially identified in Jenny Offill’s 2016 novel Dept of Speculation. Offill’s protagonist had wanted to be just such a creative monster before becoming a wife and mother. My book Weird Girls: Writing the Art Monster, looks at my quest to be an art monster despite being a mother of two.

As I wrote, I was revisiting Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy, which I’d first read at 11—Harriet’s age. Reading about my strange and wondrous Harriet, with all her art monster tendencies, became a sort of guide to the underworld of monstrous creativity for me as I struggled to finish the book before becoming entirely buried in my two kids’ SpongeBob SquarePants paraphernalia.

Harriet is, indeed, an art monster, an identity that reaches its tragicomic apex in the surreal sequence wherein a classmate dumps ink on her and Harriet becomes “the blue monster of East End Avenue.” On a more serious level, though, Fitzhugh captures the intense sensory experience of the obsessive dedication to craft required to be an art monster. For instance, Fitzhugh zooms in so we can feel Harriet “bending so low over her notebook that her long straight hair touched the edges.” Harriet spends all her waking hours “scribbling furiously” and whenever she sees most anything, she “fairly itched to take notes.” She has, in other words, the writing bug.

Harriet never goes anywhere without her sacred notebook. This is her fifteenth one; she started writing in them at the age of 8. When I read this as a kid, I immediately went out and got a green composition book of my own just like Harriet’s. As I struggled to finish Weird Girls, straining to see over my daughter’s curly head to type words of consequence, I pictured Harriet’s hair grazing her notebook, this blue monster of East End Avenue becoming the guide who could lead me over the threshold from harried mother to inspired art monster.

Reading about my strange and wondrous Harriet, with all her art monster tendencies, became a sort of guide to the underworld of monstrous creativity for me.

It’s another heavy cultural term to pin on a child, but Harriet is also a flaneur, or what Walter Benjamin described as the “essential figure of the modern urban spectator, an amateur detective and investigator of the city.” Technically, I suppose she would be a flâneuse, however the feminine version is used far less often, certainly in Benjamin’s time, which is why Harriet’s spying on her culture is even more groundbreaking. Let’s just say that the original term didn’t make room for the notion of the girl flâneuse.

When Harriet goes on her daily spy route, it allows her to investigate the lives of people from different backgrounds, alleys that “provided three vantage points from which Harriet could watch.” Something striking about the history of the term flâneur is its connection to the art monster in the sense that Benjamin called the flâneur a “werewolf roaming restlessly in the social wilderness.” And, certainly, we can see Harriet as this werewolf, tracking her subjects with an artistry that borders on the ferocious.

Throughout the book, Fitzhugh creates various portraits of art monsters that are simultaneously reverential and gently mocking of the artistic process—but only the way someone who knows and loves it inside-out could mock it. For instance, in another portrait of an artist at work, Harriet, culture vulture that she is, watches Harrison Withers (one of the people on her daily spying beat) at work on his bird cages. What we know about Harrison, through Harriet, is that he crafts birdcages and has too many cats, but we also learn that he’s an artist when it comes to creating those cages.

Case in point: “He looked lovingly, his eyes slightly glazed, at the one small unfinished portion of the structure. Very slowly he moved one piece a quarter of an inch to the left. He sat back and looked at it a long time. Then he moved it back.” This description simultaneously pays homage to and lampoons the absurd process of artmaking: the way I sit at my computer for half an hour, fueled by creative intensity, only to write six words…and then delete them. So, then, what’s it all for? Maybe, Fitzhugh seems to say, it’s ultimately about the process: the sublimity of Harriet’s hair grazing the edges of her notebook pages as she steps into her rightful role as the “The Blue Monster of East End Avenue.”

Many writers don’t love the “monster” in the term “art monster” because they worry it sanctions cruelty in the name of art. But, to me, the monster here is more about creative disruption than being “mean.”

If Harriet wants nothing more than to be a writer, her best friend Janie wants nothing more than to be a scientist. What could be more sublime than Janie Gibbs, who has a mad scientist lab set up in her room and plans to blow up the world? She’s also monomaniacally focused on her art, chemistry. In fact, Janie’s lab is a spectacular mix of Virginia Woolf’s “a room of one’s own” and Dr. Frankenstein’s “workshop of filthy creation.” Janie’s lab scares even Harriet, conjuring images of monstrous danger and creativity.

Harriet wonders if she’ll turn into Mr. Hyde if she sips from the assorted bottles there. Janie’s mother fears her daughter will blow her up and decides the solution is dance class, which will supposedly help her realize she’s a “girl.” Janie protests this absurd plan by pointing out that you never saw Pasteur, Curie, or Einstein learning the Foxtrot.

Many writers don’t love the “monster” in the term “art monster” because they worry it sanctions cruelty in the name of art. But, to me, the monster here is more about creative disruption than being “mean.” When faced with a mother like Janie’s, we can see why this sort of generative rebellion may be necessary. Though I don’t sanction acting like an actual asshole, there are times when women artists in particular must make creative choices that may be less than crowd-pleasing. For Harriet, that choice was to write things about her classmates (including Janie) in her notebook, which would later be discovered—resulting in the ink dumping incident that transforms her into “The Blue Monster of East End Avenue.”

The trope of the bad guy writer who hurts friends and family in the name of art has been done to death, but we don’t see this anatomized as often with a girl creator. Harriet appealed to me not despite but because she was willing to displease in the name of invention. When her schoolmates turn against her, she doubles down on her art monster nature, and eventually ends up finding a public outlet for her work by becoming editor of the school newspaper—specializing in the very salacious spy-like tidbits in which she excels.

Frankly, in my perennial professor-and-mother role as kindly, caretaking older lady, I wasn’t really in danger of becoming an art villain; what felt villainous to me, however, was any behavior that wasn’t selfless, such as sending my partner to the mind-numbing kid sing-along in my stead so I could blast metal, pound energy drinks, and be the werewolf roaming my own wilderness long enough to finally finish my mothereffing book. This monster imagery is crucial because it summons a sort of rogue creativity that can’t be contained, which is especially necessary for girls (and women, like me) facing a world of people, like Janie’s mother, who want to put them in dance class so that they stop experimenting and trying to, metaphorically, blow up the world.

_____________________________________

Weird Girls: Writing the Art Monster by Caroline Hagood is available now via Spuyten Duyvil.

Caroline Hagood

Caroline Hagood is Assistant Professor of Literature, Writing and Publishing and Director of Undergraduate Writing at St. Francis College in Brooklyn. She is the author of two poetry books, Lunatic Speaks and Making Maxine’s Baby, a book-length essay, Ways of Looking at a Woman, and a novel, Ghosts of America. Weird Girls: Writing the Art Monster is her latest book.