An Oddly Poetic Account of Colorblindness from the Turn of the Last Century

"We may aptly term color the music of light."

The relation of color to light is much the same as that of music to sound. Color has its many hues, its long scales of tints and shades, its true and its false chords. Mere sound gives us but little pleasure; when developed, however, into its highest form, music, we are thrilled, as by the song of a bird, a favorite ballad, or a Beethoven Symphony. So in light, our enjoyment culminates at the glories of color in a flower or a sunset, at the shadows that play over the hills, or at the varied hues of a salt marsh. Hence we may aptly term color the music of light; and when we think of the wonderful ways in which it has been used and combined by painters and designers for hundreds of years, it must seem strange to us that its harmonies have not been as thoroughly studied and classified as those of sound.

Furthermore, color has come to be so closely connected with all the occupations and enjoyments of mankind that it is hard for us to realize that many persons are wholly or partially blind to its beauties. It is well known that there are some individuals with such perfect organs of hearing that they are able to distinguish the slightest sounds, who yet are so utterly unable to distinguish between two tones or between the harmonies and discords of music that they are said to have “no ear.” So there are those whose eyes are as well formed for seeing all and distant objects, but who are unable to see color as it is seen by people with normal eyes. Such individuals may be said to have “no eye” for color, and are scientifically termed “color-blind.”

This fact is not so well known; and, in view of it, anyone interested in color will understand the wisdom of beginning a study of color with some knowledge of color-blindness, and, if possible, with having his eyes examined by an expert. Such an examination is a short and simple matter. Dr. William Thomson of Philadelphia has devised what he calls a “color stick,” on which colored wools are so hung and numbered that it is not even necessary to be an expert to use it, and with the help of which color-blindness can easily be detected. It has been used with great success over some 50,000 miles of railroad. From the same hand has lately come a newer and simpler form of the same invention.

Color-blindness is seldom a total want of the power to see colors, but is rather a want of the true normal perception of colors, and it is more common than is generally supposed. The most common form of the defect, which has been called by some “red-blindness,” is that of not seeing red, but of confusing it with green, as, for instance, being unable to see any difference between the red flower of a geranium and the green of its foliage; between green grass and red autumn leaves. A color-blind person will sort variously colored wools in the strangest way, putting the reds among the greens, and mixing the blues and the violets together.

In an examination of a color-blind man by Doctor Thomson, the patient was given 150 different colored wools to sort in little heaps according as he saw them to be red, blue, green, etc.; he seemed to hesitate over but few of them. These he put by themselves in a heap called neutral. To a normal eye the result is almost incomprehensible, as he mixed green with all the other colors and made other as strange combinations. Dichromatic vision has been suggested as a fitting term for such defective color perception, as colors to red-blind persons amount to but two, viz., yellow and blue, with a long range of neutral grays between.

There is a noted instance of a man who learned in later life that he was color-blind, and then first understood why he had never been able to pick as many strawberries as his boy companions.

There are other forms of color-blindness which are less common. Some persons seem to see but red and blue, classing yellow and green with red. A less common defect is that of not seeing violet, while there are a few cases on record where all sensation of color is wanting, everything appearing in differing degrees of gray. One such instance coming under the notice of the writer occurred temporarily from over-strained nerves in a person gifted with an abnormally fine color sense. No doubt some people are born color-blind, but the defect is also brought on by disease, by the excessive use of tobacco, alcohol, and other stimulants, and may, or may not, prove permanent. According to Abney, the disease begins in the centre of the eye, so that those suffering from its early stages can match colored wools correctly, but when given instead small colored pellets to match make many mistakes, because a pellet may happen to be directly before the small blind spot that is insensible to its color, while the larger mass of wool extends before the whole retina.

Doctor Charcot and his school in Paris have made many examinations into visual disturbances, and through these examinations much of the peculiar coloring and mannerism of some of the modern painters of the so-called impressionist, tachist, mosaist, gray in-gray, violet colorist, archaic, vibraist, and color orgiast schools has been explained. The artists tell the truth when they say that nature looks to them as they paint it, but they are suffering from hysteria or from other nervous derangements by which their sight is affected.

For a long time railroad engineers would not believe that examinations for color-blindness were necessary, but when shown the results of such an examination the surprise of those with normal eyes was intense. They realized what it would be to travel on a train in charge of an engineer who did not know when the red danger signal had been put in place of the usual green one. In other spheres of life correct knowledge of color is not so vitally necessary, yet to artisans of many kinds—decorators, florists, manufacturers, dressmakers, milliners, etc.—it is both useful and important.

As to the extent of color-blindness, it has been estimated that in England about one person in 18 is more or less afflicted with it. In 1873 and 1875 Dr. Farre examined in France 1,050 officials of various grades, and found among them 98 color-blind, or [nearly 10 percent]. In 1876 Professor Holmgren examined in Sweden 265 persons on the Upsala Gefle line, with the result that 13 were found to be color-blind. Seebach found 5 young persons out of 41 in a gymnasium who were color-blind. None of them had been at all conscious of the defect.

Among the visitors to the International Health Association in London, in 1884, Mr. F. Galton found a large number of men and a small number of women with more or less defective color-perception. In this country, examinations in the army and navy and among railroad engineers reveal that color-blindness, if not as general as in England, is quite common. Dr. Thomson states that as far as has been gathered from statistics generally, the percentage of color-blind men in the civilized world is four percent, or 1 in 25—among women 1 in 4,000. While he has seen a great number of color-blind men he has never met a woman with the defect.

Singularly enough this color-blindness—the confounding of one color with another, or the want of perception of certain colors—does not prevent great enjoyment of both nature and art. A person so color-blind as to see no difference between the scarlet of a geranium blossom and the green of its leaves, or who buys a pair of bright green gloves supposing them to be brown, is still an enthusiastic and seemingly an intelligent admirer of landscape and art. One cannot say from what the enjoyment arises, but it is certainly there.

There is a noted instance of a man who learned in later life that he was color-blind, and then first understood why he had never been able to pick as many strawberries as his boy companions, because with his defect he saw no difference between the colors of the berry and that of its leaf.

There is, however, a very simple way in which it is possible for some color-blind persons to correct in a measure their erroneous impressions. If they have something green to match and fear they may mistake red for the green, by looking at their samples through a green or red glass they can prove whether or not they are correct. Through a green glass the green will keep its color, while the red will look nearly black. Through a red glass the red will remain unchanged and the green will seem nearly black.

Color-blind people can have colored glasses mounted as spectacles at small cost, which will almost entirely relieve their defect and be of great help in their work.

·

·

How far the eye of a color-blind person is susceptible of education is still uncertain. Sufficient experiment has not been made in that direction, but the fact that women notice color more than do men and are, as a general rule, more correct in their judgment of color, points to the fact that the eye is unconsciously educated by its surroundings. The constant discrimination in choice of dress and home decoration which enters early into a girl’s life gives an education which men, in Europe and America at least, are deprived of, from generally wearing black or quiet colors.

That an eye normal in its perceptions of colors is capable of cultivation cannot be doubted. “It does not admit of doubt that individual sensibility to color admits of large variations, and that it is susceptible of immense improvement. This cultivation of the sense of color is, however, rather psychological than physiological, rather mental than physical. It is not that the organ of vision is improved, but our power of interpreting and coordinating the senses which it transmits to the brain. And here it is that the effects of association come most prominently, though often unconsciously, into play. We try to trace out the causes of the vast numbers of color sensations which we are continually receiving, but we constantly find that the cold methods of analysis fail to explain the mental appreciation with which we regard the astounding fertility of nature in its gifts of color.”

Artists often find that when the eyes are over stimulated by false lights or colors, or want of balance in the colors looked at, the nerves are so irritated that a confusion of color and complementary tones takes place. If continued to any length of time the nerves become so fatigued that the color sense is lost, and the eye responds only to gradations of black and white.

That there are also subtle shades of difference in the sensibility to color even of good, normal eyes, no one who has paid any attention to art can fail to know. These shades of difference it is impossible to gauge, and they can only be known by the differing qualities of work produced. In a studio where perhaps a dozen pupils may be painting from one piece of still life, a vase, or bit of drapery, such differences can be clearly seen. One pair of eyes may have a tendency to see more violet than the others, another pair sees everything more brilliantly or in a higher key than the others. One student may have more difficulty in harmonizing on his canvas the different colors of the model than the rest, while another with perhaps less skill in using the paint may have such a fine eye for harmony as by the mere charm of his color to delight every one in the room.

There comes with advancing years a subtle change in the condition of the eye which it is well to understand. With age the lens of the eye loses its purity or whiteness and becomes tinged with yellow. This is not generally known, and the change is not always strongly marked, but it produces a decided effect upon the perception of blue and bluish colors. The case of the English painter Mulready may be cited as a good instance. His pictures in his later years were different in color from his earlier ones, being much colder in tone, that is bluer or less yellow. If, however, they were looked at through a piece of slightly yellow glass they appeared of the same coloring as his earlier work, painted when his eyes were normal.

__________________________________

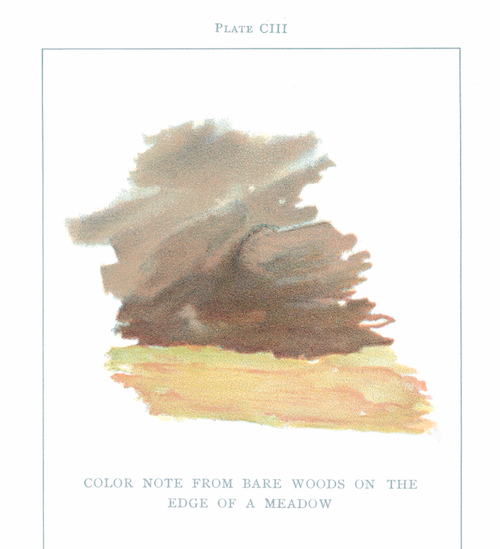

From Color Problems: A Practical Manual for the Lay Student of Color. Excerpted with permission from The Circadian Press with Sacred Bones Books, 2018. © 1901 Emily Noyes Vanderpoel

Emily Noyes Vanderpoel

Emily Noyes Vanderpoel (1842-1939) was an artist, collector, scholar, and historian working at the dawn of the 20th century. Her work in color theory was decades ahead of it's time in design aesthetics and interpretation.