An Incomplete Guide to Literary References in Twin Peaks

Or: a compendium of stylish books on Tibet

Hey, did you know that there’s a new season of Twin Peaks? Oh—you did? Why, have people been talking about it? And scene, with my sincere apologies. Like many of you, I’ve been thinking about David Lynch and Mark Frost’s beautiful, bonkers universe quite a bit lately, now that it’s returned to us after the promised 25 years (and change).

Twin Peaks is, among other things, famous for its abundance of references, whether cinematic, historical, literary, or some category more nebulous than any of these. But since this is a literary website, it’s literary references in the first two seasons that I’ve decided to investigate here. Of course, it’s impossible to track down every single literary allusion in a show like this (without devoting my life to it, I mean), and I’m sure I haven’t even scratched the surface—though Twin Peaks Online has helped quite a bit—but this should at least get you started on a good nerdy rabbit hole. NB: spoilers, necessarily, abound below. But honestly, you’ve had over 25 years, so I don’t want to hear it.

Episode 16 (or “Arbitrary Law”) brings us Leland Palmer’s legendary death scene. In Lion’s Roar, Rod Meade Sperry points out that Cooper’s comforting language paraphrases a relevant section in The Tibetan Book of the Dead—of which we already know Cooper (and David Lynch, no doubt, being a practitioner of Transcendental Meditation) is a fan:

Quoth Cooper:

Leland, the time has come for you to seek the path. Your soul has set you face-to-face with the clear light, and you are now about to experience it in all its reality, wherein all things are like the void and cloudless sky, and the naked, spotless intellect is like a transparent vacuum, without circumference or center. Leland, in this moment, know yourself, and abide in that state… Look to the light, Leland. Find the light.

Compare to this passage from The Tibetan Book of the Dead, meant to be recited to a dying person:

O, nobly-born [so-and-so by name], the time hath now come for thee to seek the Path [in reality]. Thy breathing is about to cease. Thy guru hath set thee face to face before with the Clear Light; and now thou art about to experience in its Reality in the Bardo state, wherein all things are like the void and cloudless sky, and the naked, spotless intellect is like unto a transparent vacuum without circumference or centre. At this moment, know thou thyself, and abide in that state.

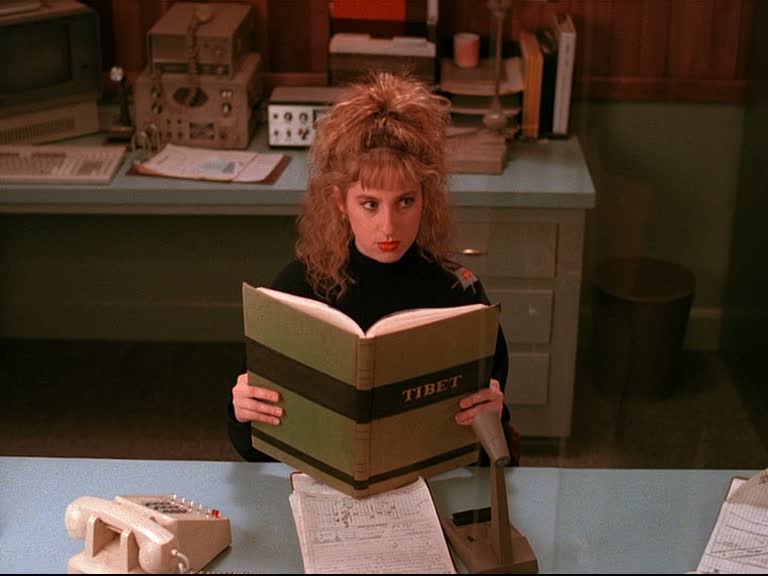

Cooper gets Lucy interested in Tibet, too.

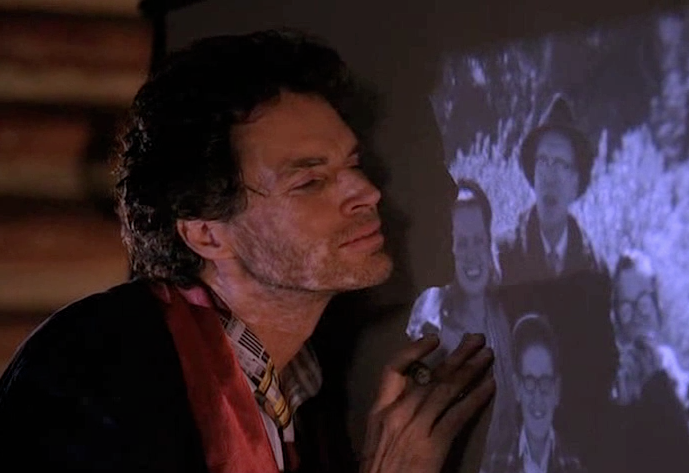

In Episode 18 (or “Masked Ball”), a distressed Ben Horne watches old home movies and quotes Richard III: “Now is the winter of our discontent made glorious summer by this son of York,” he says, crying and smiling at once, moving to kiss the projected image of his mother. In “The Owls Are Not What They Seem,” an essay in Return to Twin Peaks: New Approaches to Materiality, Theory, and Genre on Television, Sherryl Vint unpacks this moment, pointing out that this is

the soliloquy in which Richard, unhappy in a world that hates him, announces his intention to “prove a villain” since, it seems, he cannot be loved. Ben quotes only the opening line of the soliloquy, the announcement that the period of unhappiness has passed, and his meaning is ambiguous: is the “winter” the period between the disruption of the woods by the hotel, and his new plan to save the woods? Or is the “winter” the present that Ben is about to abandon in favor of an idealized past? Is he converted, or declaring his villainy like Richard III?

By the way, Ben spouts quite a lot of Shakespeare in this series. In “Zen, or the Skill to Catch a Killer” he recites Sonnet 18 (“Shall I compare thee to a Summers day” etc.) to Blackie, the madame at One Eyed Jack’s.

Ben goes on to wheedle the new girl at One Eyed Jack’s with more Shakespeare, this time from The Tempest—”This is such stuff as dreams are made of”—not knowing that the new girl is his daughter Audrey. And don’t forget the alias Audrey uses when she comes to work there: Hester Prynne. (In case you can’t remember anything from high school English, that’s the name of the protagonist of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter.)

In “Checkmate,” we find out that the repeatedly orphaned Nicky Needleman (aka “Little Nicky”) lives at the Dorrit Home for Boys—which can only be a reference to Little Dorrit, by unfortunate orphan-obsessive Charles Dickens.

It’s not only Ben Horne who’s a fan of the bard—Dick Tremayne is moved to quote from Romeo and Juliet at the sight of Lana Milford in “The Black Widow.” O, she doth teach the torches to burn bright! . . .

In that same episode, Pete Martell toasts Catherine with some slightly mangled Yeats—”Wine comes in at the mouth, love comes in at the eye; I hold my glass to my lips, I look at you and sigh . . .” (from “A Drinking Song”)—and an aborted limerick. Later, Earle too quotes Yeats, when trying to get into the Black Lodge: “When Jupiter and Saturn meet, Oh, what a crop of mummy wheat!”

Only about six months ago, a reddit user asked Mark Frost if the relationship between Windom Earle and Leo Johnson at the end of season two—a relationship, if you remember, that consists of Earle keeping Leo as a slave with an electric collar—had any relationship to Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, in which Hamm keeps Clov as a slave. “You’re the first person to get the Beckett reference,” Frost responded. Honestly, that guy should put that on his business card.

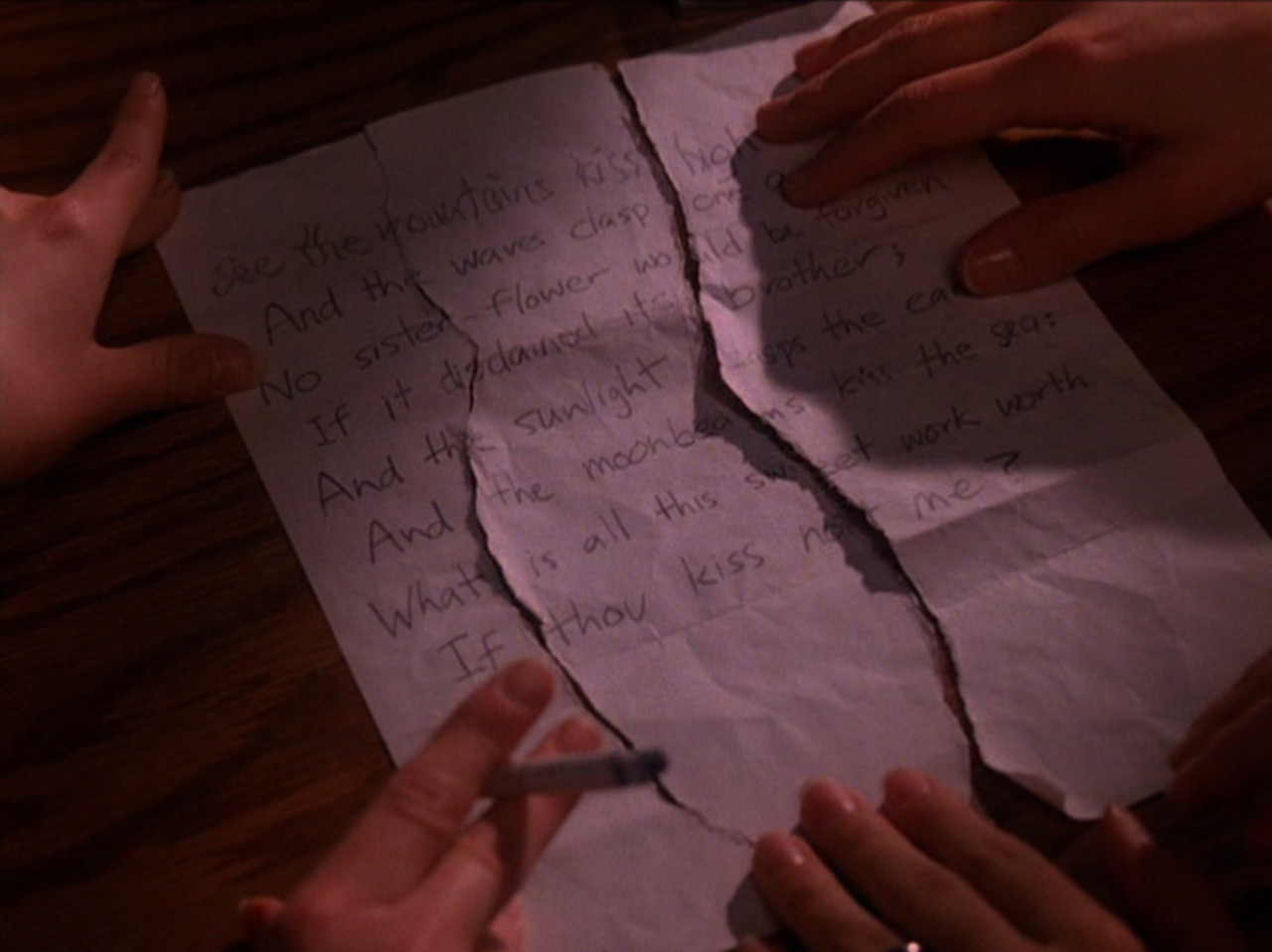

Speaking of Windom and Leo—near the end of the second season, Windom has Leo transcribe the second stanza of “Love’s Philosophy” by Percy Shelley, then rips the paper in three and sends one section each to Audrey, Donna and Shelley, along with a note: Save the one you love. Please attend gathering of angels tonight at the Roadhouse 9:30. “Which one shall be my queen?” he wonders.

The Black Lodge and the White Lodge and the Red Room seem to be literary references—but from where?

At Dazed, Anna Cafolla points out (as it has been pointed out elsewhere) that the Black Lodge also appears in famous occultist Aleister Crowley’s Moonchild, in which rival gangs of magicians fight over a child. “It’s said that [Crowley] taught his followers the Occult Law of Reversal, which involved talking, walking and thinking backwards for those who want fame or power,” Cafolla writes. “[T]his is something Lynch uses in the Black Lodge, in some of the scariest scenes, where the cast spoke their lines backwards, which were then reversed in the editing process to make it sound creepier.”

Another reader has noticed connections to William S. Burroughs’s 1981 novel Cities of the Red Night, which seems even more pointed given the rumor that Lynch wanted to cast Burroughs as Mayor Dwayne Milford:

Cities of the Red Night makes specific mentions of Black and White Lodges and features non-linear plotlines regarding space and time–a key feature of the lodges in Twin Peaks. One of the novel’s protagonists, a detective named Clem Snide, is searching for a missing boy and uses the ancient Chinese text, the I Ching, to aid in his investigation. Likewise, Dale Cooper is investigating the death of Laura Palmer and uses ancient Tibetan methods to solve the murder.

But, I suppose we should take it from the horse’s mouth—Mark Frost has admitted that the idea for the Black Lodge came from Psychic Self-Defense: The Classic Instruction Manual for Protecting Yourself Against Paranormal Attack by notorious occultist Dion Fortune. “The whole mythological side of Twin Peaks was really down to me,” Frost said, “and I’ve always known about the Theosophical writers and that whole group around the Order of the Golden Dawn in the late 19th, early 20th century—W.B. Yeats, Madame Blavatsky and a woman called Alice Bailey, a very interesting writer.”

Then there’s The Devil’s Guard, a 1926 novel by Talbot Mundy, which, according to Twin Peaks FAQ, used the terms White Lodge, Black Lodge, and dugpa, “even describing dugpas as sorcerers who ‘cultivate evil for the sake of evil . . . 65 years before Windom Earle spoke the exact same line.”

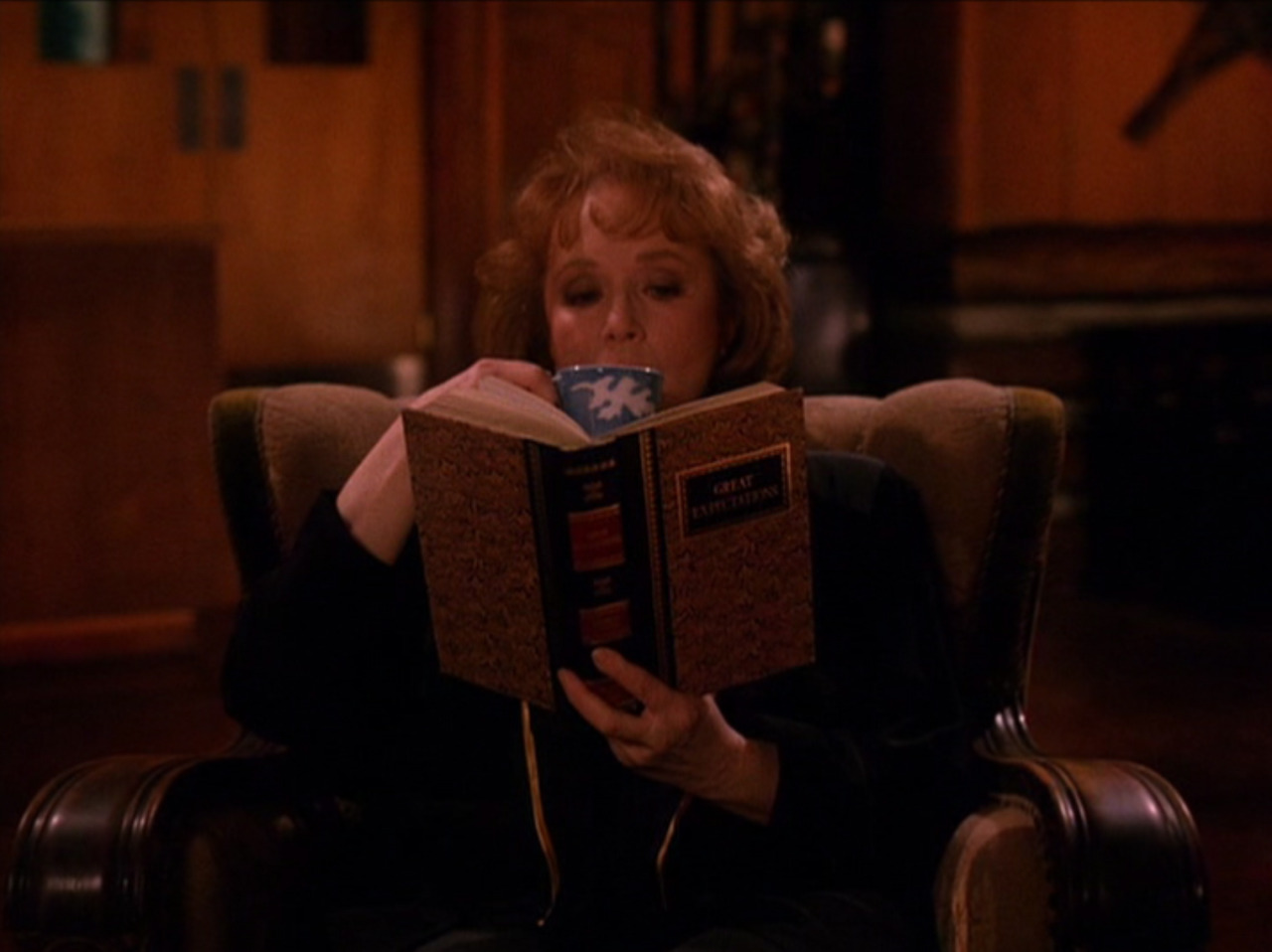

Last but not least, here’s Catherine Martell reading Great Expectations in “The Condemned Woman.” This book (the very same?) also appears on Cooper’s bedside table now and again.