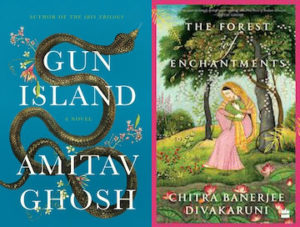

Amitav Ghosh and Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni on Indian Epics in Modern Novels

The Authors of Gun Island and The Forest of Enchantments in Conversation

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni and Amitav Ghosh are both authors whose works offer razor-sharp insight into overlooked members of society—men and women caught in power systems beyond their control who nevertheless try to find meaning and connection. Their books lovingly explore Indian culture for a global audience, fusing the mythology of such seminal Indian epics as the Mahābhārata and the Ramayana with a modern exploration of such issues as migration, diaspora, and identity. They recently sat down to discuss their work past and present. This is their conversation.

*

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni: In reading your novels, while I’m fascinated by the story and characters, I’m most impressed by the meticulous research that you do—not only for your historical novels, but your other ones, as well. Research is important to me, too, particularly in my retelling of Indian epics. Can you share something about what research means to you, and how you go about it? I’d love to compare methods and objectives.

Amitav Ghosh: To me, one of the most interesting bits of the research process is reading old texts in the original (as you’ve done with various versions of the Ramayana). I think that is the only way one can get a feeling for sensibilities that may be profoundly different from one’s own. As far as the Ramayana, and other Indian epics and myths are concerned, the originals are of course always in verse. This is, I think, a very important part of that kind of story-telling because poetry transports the reader out the domain of the prosaic. There have been some interesting attempts to translate the epics into English verse (you may be familiar with Carole Satyamurti’s “Mahabharata”). So here’s my question: did you ever think of telling the story of your new novel, The Forest of Enchantments, in verse rather than prose?

CBD: I spent about 10 years—the time between this novel and The Palace of Illusions, my retelling of the Mahābhārata in Draupadi’s voice—reading various versions of the Ramayana (all in verse) and thinking about them. I started my writing career as a poet—something that I am thankful for, as it has made me much more aware of the nuances of sound and imagery, and I hope I’ve brought that understanding to Forest. But I definitely wanted to write it in contemporary prose as I think of the characters—especially Sita—as timeless and, indeed, modern. I wanted readers to relate deeply to the decisions she makes when in situations of difficulty and be inspired by her courage. And I felt contemporary prose would be the right medium to convey her relevance to the problems faced by women today. (She is one of the first characters in literature who deals with single parenting, for instance—and she does it most gracefully.)

I’m loving Gun Island and am quite fascinated by the Bengali Manasa legend that is central to that novel. I think old Bengali legends/writings have a particular power of their own and are more centered around women. (While researching Forest, I was most taken by Krittibas’ version of the Ramayana, which gave more space to women characters than Valmiki.) How—and why—did you come to choose the Manasa story, which I remember my mother telling me long ago? What has been the role of legends in your work?

AG: I’ve always been interested in legends but this interest grew stronger after I began thinking about climate change. In my 2016 book, The Great Derangement, I tried to examine the reasons why climate change hasn’t had its due place in my own work and in modern literature more generally: this is after all the greatest challenge that human beings have ever confronted. That got me to thinking about whether pre-modern literature approached weather phenomena and extreme events in different ways.

And of course, that is indeed the case. This is particularly so in the case of the legends around Manasa Devi, the goddess of snakes. She is, in a sense, the goddess not only of all poisonous creatures, but of disasters and calamities in general. I think it’s perhaps not a coincidence that the Manasa legend (which is very, very old) had a revival in the 17th century, which was a period of severe climate disruption around the world. This was a time of major epidemics, so it’s probably not coincidental that the legend of Shitala Devi, the goddess of smallpox, also went through a revival in that period. So I do think these traditions can serve as a very important resource for us, as we head into a time of climate crisis. Of course there can be no going back—we can’t write in those ways. But we can draw on those resources: certainly my readings of the Manasa legend did serve as a direct inspiration for Gun Island.

What interests you about these legends?

CBD: Reexamining epics and legends gives me a chance to tease out important themes in them that are relevant to today’s world, and to put my own spin on them. In both Palace of Illusions and Forest of Enchantments, I’m interested in how the original texts, the Mahābhārata and Ramayana, bring up questions of morality, but I’ve tried to examine them as a woman who lives in today’s world and is concerned about the particular form these questions currently take. In the Mahābhārata, a major theme is righteous revenge—and Draupadi, my protagonist and narrator of The Palace of Illusions, is a major catalyst for revenge and the war that follows. I have a scene where she goes through the battlefield afterwards (this is not in the original text) and is shocked by the devastation she has caused in pursuing honor.

I wanted my readers to think about not just the glory but the price of vengeance and war—something still sadly relevant in today’s world. In Forest of Enchantments, an important theme is the encroachment upon nature, and the way of life of the forest, by people from “civilization.” My Sita questions the unthinking destruction of trees and plants, and later, the killing of the rakshashas by Ram and Lakshman. The ancient legends also bring up complicated questions concerning female sexuality and its limits, and I’m interested in reexamining this. In Forest, a major incident is the mutilation of Surpanakha—whose main fault is that she desires a relationship with Ram—by Ram and Lakshman. My Sita is greatly troubled by this.

In Gun Island, your protagonist Deen is an Indian-American—as opposed to earlier books, where protagonists were mainly from the subcontinent or surrounding countries. So is his friend Pia. Has living in America made you more interested in the immigrant experience (a subject I find endlessly fascinating) and if so, what aspects of this experience are you most interested in exploring? On a personal level, I know you’ve moved a lot between America and India. How has that influenced your writing?

AG: The movement of people—whether we call it immigration, dislocation, transportation, or whatever—has been a recurrent theme in my work going back to my first novel. I think this may be because, as I’ve written in The Great Derangement, my own family were environmental refugees, way back in the mid 19th century. They started moving because their village, in what is now Bangladesh, was drowned in a flood—and they never stopped. Dislocation and immigration are central themes also in Gun Island because of displacement is one of the most significant impacts of climate change. I became particularly interested in this aspect of our current reality some years ago during the European migration crisis, when I noticed that among the refugees who were crossing the Mediterranean, from North Africa, there were large numbers of South Asians. Over the last few years I’ve spent a lot of time speaking to refugees in Italian camps. The experience has been a real eye-opener for me, and deeply moving too, because many of the migrants are from exactly the part of Bangladesh that my family left in the 19th century. Would you say that immigration has shaped who you are as a writer?

CBD: Yes, definitely. Immigration made me into a writer by thrusting me, at the age of 19, into a world very different from the Kolkata environment where I grew up cocooned by an extended family. In America I was alone in a foreign land, and this forced me to introspect upon the immigrant condition. From the first, I became interested in chronicling, in fiction and poetry, the lives of people like me, Indian-Americans who were being transformed by the US even as they were transforming it. Several of my books go back and forth between India and America, chronicling immigration to the west and sometimes, the return to the east.

Living abroad also changed my relationship to India. It made me value, in a whole new way, the culture and tradition I’d left behind. It made me see it more clearly—both its treasures and its problems. It made me go back and study ancient texts such as the Ramayana (books I’d taken for granted when living in India) in an effort to understand this culture, and the ways in which the ideas in the ancient texts still remain relevant.

I don’t think I could have written either Palace of Illusions or Forest of Enchantments if I’d never left India.

Looking back at your writings, do you find that there a particular book, or set of books, that you are most happy with? Your chef d’oeuvre, so to speak? Can you say something about that?

AG: I really can’t say that I feel there is any one book that I would pick out as my chef d’oeuvre. My readers also seem to vary a lot in their opinions about which of my books they like best. I suppose I’d say that every book is (among many other things) a response to the pressing concerns of the moment. Speaking of which, immigration is of course a very burning issue, not just in the US, but across the world. It must be especially so in Texas, where you live. I’d love to know your thoughts on this matter.

CBD: Immigration has always been an issue in the US, but it’s especially fraught at the moment. I remember writing my novel Queen of Dreams in 2004 about the post-9/11 violence toward immigrants in the US. Sadly, such a book seems even more relevant now. Living in Houston, which is pretty cosmopolitan, and teaching at the University of Houston, I am surrounded by liberal thinkers, but if I travel out into the countryside and especially toward the Mexican border, I can feel the tension. Visible immigrants like us (and our children, who ironically are not immigrants at all) are looked at with new suspicion. You would know more, having worked with refugees in Europe. What are your feelings?

AG: Ten years ago, if anyone had said to me that migration would be the issue that would lead to a sea-change in European and American politics, I wouldn’t have believed them. But that is indeed what has happened—and it is an indication that our social and political systems are much more sensitive to climate disruption than anyone could have imagined. That does not bode well for our planet’s increasingly unsettled future.

But let’s come back to the question you asked me: what do you think of as your own chef d’oeuvre? And where does The Forest of Enchantments figure in your work?

CBD: It’s hard to judge one’s own work, as you said, but perhaps The Palace of Illusions and The Forest of Enchantments are my chefs d’oeuvre. I see them as a pair, with Draupadi and Sita providing two very different models of female resistance in a patriarchal society. I’d always wanted to explore these characters; until ten years ago, I didn’t feel ready. Perhaps I had to grow, myself, as a writer and as a woman. I’ve received many comments, particularly from women, about these books transforming their ideas about their role and their potential in the world. That makes me feel at once humbled and happy.

_______________________________________________

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s The Forest of Enchantments is out now from HarperCollins, and Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island is out September 10 from FSG.

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s The Forest of Enchantments is out now from HarperCollins, and Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island is out September 10 from FSG.