Aminatta Forna and Maaza Mengiste: A Conversation and Cover Reveal

The Window Seat, an Essay Collection, Comes Out Next May

Tumbuktu, Tehran, London, Freetown, Honolulu, New Orleans. These are but a few of the compass points visited in The Window Seat, Aminatta Forna’s debut collection of essays, which Grove/Atlantic publishes in May next year. As a reporter and traveler, Forna has been studying flight and movement for her entire life. She has also lived in its wake. Just as Barack Obama, Sr. departed Kenya for America for an education, Forna’s own father left Sierra Leone to study medicine abroad.

Raised between countries, with a front row seat to ruptures of history, Forna muses here on what it means to live in a world shaped by travel of choice and necessity. How to appreciate the wonders of flight while also acknowledging the terror which prompts less metaphorical flight. As the child of a doctor, who one day wanted to be a veterinarian, Forna also returns such questions to the biosphere. What does the way we treat animals and landscapes say of our capacity to share any space? How will we ever appreciate the gulf that stands between us and every other species, for whom migration is often crucial to survival?

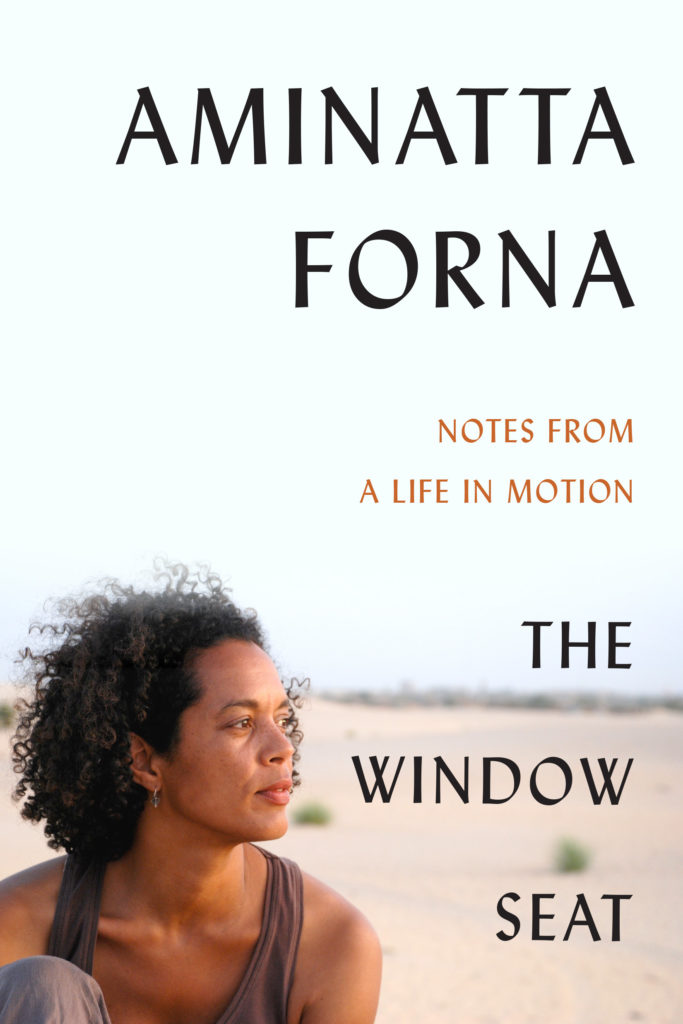

Recently, Forna spoke over email with novelist and friend Maaza Mengiste, whose latest book, The Shadow King, was a finalist for the 2020 Booker Prize. Mengiste, a photographer, and Forna, a former broadcaster and documentarian, spoke about what it means to imagine history and the idea of far away elsewheres. They also talk about what an image like the one which adorns Forna’s cover means in 2020 America.

Maaza Mengiste: I keep staring at this photograph, at the vastness of the landscape around you. What a far cry from the place we find ourselves now, in the midst of a pandemic. Where were you and how did this photo come to be?

Aminatta Forna: The photograph was taken in the Sahara desert just outside Timbuktu. I was filming a documentary, The Lost Libraries of Timbuktu. During a pause in filming the cameraman, John Christie, took that picture of me. Mali is a country for which I have a great love, it has such a rich history and I have been there several times. People in Timbuktu find it a source of great hilarity that many Westerners think of their town as representing the ends of the earth.

We were filming in November 2008 and in the United States Obama was elected president. People in Timbuktu didn’t see Obama—a man with a white mother—as a black man, a perception that is fairly common throughout black Africa. People viewed Obama through the prism of their own blackness, compared to which Obama looks rather pale. (Africans would later come to claim him, but that should be no surprise as he was the most powerful man in the world). This is a difference in perspective, as is the one that puts Timbuktu is at the center of the world. What you see depends on where you are standing.

MM: I’m struck by several things in your response. The first is the fact that you were in the Sahara to film a documentary about the lost libraries of Timbuktu. There are layers of history to unpack here, and ways of seeing an entire continent. The ancient libraries and schools in Timbuktu offer evidence of a city that was a vibrant and rich intellectual center. They prove that Africans were engaged with texts, with the written word for centuries. There is a profound respect for knowledge and reading and it was palpable in the documentary. The residents risked so much to save their written history and I saw their efforts as a refusal to give in to forces that could eventually erase them from all memory.

It was disconcerting to watch this BBC documentary in 2020 America, where we have been struggling against an administration that has rejected science and the intellect. Looking back at your experiences making this documentary, are there lessons about history, about memory or the written word, that you have carried forward up to today? Is there anything that comes to mind from those times in Mali as we begin to transition from one president who has no regard for literature, to another who seems to echo the hope of the Obama years?

AM: Today the world is engaged in a full scale combat of narratives, ranging across religion, science, history and much more. We have both—you and I—grown up knowing that every narrative has more than one version. The people of Timbuktu hid their manuscripts from the French invaders in the late nineteenth century and again a few years ago from Islamist invaders. The name of their city became a metaphor for all that is distant and unreachable. However the people living there never forgot who they were. In time they told their story again. I remember talking to a Songhay chief once, who laughed when I mentioned the French Empire. “Call that an Empire? They didn’t even last a hundred years.” And he described all the Empires that arose in and around Mali over centuries. I had that same sense when I visited Ethiopia, I saw the way people carried themselves. You have written about this in your book, The Shadow King. The people of Ethiopia summed it up in just one word—Adwa!

A large part of our identity is bound up in narrative, the stories we are told, those we tell ourselves, stories that are told about us. Psychologists have just given a name to something writers have always inherently known—“narrative identity.” I grew up at a time when, in Western literature, Africans were mostly absent or silent, my parents and people around me gave me an alternative narrative, one that enabled me to envision a future for myself. As a child I was also blessed with a powerful imagination, untrammled by any facts that might be considered limiting, including geography or historical timing or indeed, my own sex. I was lucky.

At the same time as I was growing up, other children were being told different kinds of stories, or perhaps some of the same stories but they interpreted these stories differently from me. It has taken me perhaps longer than it should to begin to imagine how that might be. What might that be like? In the comic strips, the movies, the novels, it is always you who slays the dragon, always you who gets the girl, always you who makes millions, who saves Metropolis. Who saves the world!

Or put another way, it is never you who always dies before the end of the movie. It is never you who only is only depicted as a wife or a servant. That’s not your bodice ripped and your breasts exposed on the cover of the dime store novel. Or, in today’s world, whose naked corpse is found by an early morning jogger. You’re not the one who is beaten, sold and enslaved. And when a writer addresses readers as, “you,” they actually meant YOU.

In other words, what is it like, as a reader, to be the heroic default setting for virtually every book you have ever read? Now I find myself trying to imagine something else, and that is what it is like to be faced with the possibility that stories aren’t really true—in the deepest sense—but created, told and retold in pursuance of an endeavor of another kind, sometimes deliberately, sometimes reflexively—in promotion of the idea of Western singularity. You have grown up being told you are special. Now you’re told that you’re not special anymore. And also, you learn a lot of people never really thought you were that special. There’s a reckoning to be done. When someone rejects intellectual pursuits and instead clings onto the symbols and stories of the past, what we are witnessing is the anger of that child.

MM: I’m thinking of the anger of that spoiled child, that petulant and misinformed child that insists that the world be remade in his own image, no matter the cost. It brings the last years of this administration to mind, but also makes me think of centuries of American and Western history—that grand narrative of the world that erased entire groups of people. Those of us on the continent were never meant to speak up, to answer back and to re-write this narrative. We were meant to stay in our place, and stay quiet.

I think of the many generations that struggled and fought so you and I could have this conversation as travelers of the world (with accommodating visas). The cover image, then, has an added significance for me: it implies the ease of movement that I—and you, I suspect—took for granted until this pandemic. For others, mobility has always been difficult, always been a “full scale combat” for survival. Your book touches on some of this, too. Could you talk more about your experiences in this photo with travel—with getting there—but also moving on from there, to those many places you write about?

AF: My family have travelled for every reason: education, work, safety from persecution, from war, and finally for pleasure. I was in my twenties before the idea of taking a vacation overseas occurred to me. Even then I was compelled to visit places where I might discover things about the world I didn’t know, combining my work as a writer with those journeys, so I was really exploring and reporting. To South Africa as soon as the overthrow of apartheid made that possible for me, I wanted to see the country before it had the opportunity to change too much. I’ve been back twice recently. I heard a lot of complaints about the country. What I saw was that South Africa had come a long way. It wasn’t even possible to walk around Cape Town when I was first there. Now here were people sitting in cafes and window shopping and these were the same people complaining. One morning in 1995 I leapt out of bed and said to my new husband, Quick! Let’s go to Cuba before Castro dies. If I’d known it would be another 12 years I might have been in less of a hurry. But I think I was aware the world was changing and fast, the Berlin Wall had come down, I wanted to witness the old order. You mention the cover image, taken in Timbuktu. That too has changed, overrun by Islamists. Right now travel there is dangerous and unwise.

Now I have a young son. In 2017 we took a beach holiday, to Florida. We were staying in a lovely B&B and on the first morning met a couple who had checked in last minute because beach at the hotel where they were staying had been overwhelmed by sargassum weed. I said to my husband, there’s obviously no getting away from these people and I really want to know how they think, so can you not get into any rows. We spent a lot of time with them, comparing the political process in the US and UK. They were very interested in the tradition of Prime Minister’s Question Time, in the restrictions on political donations. Like so many Americans, they had never travelled overseas. They said they would travel when they had retired, but that doesn’t seem right to me, for by then it is too late to reshape yourself.

As you say, I have always travelled with ease. So now, in this current pandemic, for some—who don’t have the money or can’t get a passport, or the right passport—the restrictions on movement will make little difference. Others—those who travelled with ease, now know something of what it is to be restricted. I have realized how much of my travel as an adult has been prompted by curiosity. So what to do with that curiosity now? I think this is the time for contemplation (for those of us whose lives and livelihoods are not at risk). I heard recently from a man I met with my husband when we were traveling in the Himalayas thirty years ago. After decades of solo travel he lives there now as a hermit—his word—who leaves his hut only for two or three times a year. ‘Strange lifestyle in the modern world, but with forerunners in many cultures,’ he wrote. He spends the rest of his time growing vegetables and in contemplation. There is something to be said for stillness. If for no other reason than a preparation for old age.

MM: There’s a scene in Abderrahmane Sissako’s stunning film, TIMBUKTU, where one of the fundamentalists enforcing stringent rules is on a rooftop, dancing. He’s doing the very thing he and other Islamists are punishing others for, and in that scene, despite his movements, there’s a stillness there. Something is held still—paused—so he can express his body’s natural inclination towards flight. This moment, out of several, comes back to me often. Years ago, when researching and writing about a catacomb in Palermo that holds mummified bodies, I kept coming around to this fact: the body’s most natural state is movement. We are always in transition, in transformation, even after life. We have traveled as a way to accelerate certain transformations, to reshape ourselves as you say so wisely. But we’ve come to a screeching halt.

You ask a profound and necessary question: What do we do with our curiosity now? I’d like to ask this back to you. Where do you think our curiosity has gone? And what do you think will happen when we can move freely again?

AM: I love that film. Our conversation has gone full circle back to Timbuktu. I first went to Mali to report on the Tuareg uprisings against the Malian government of the Nineties. A very large part of the problem was caused by the loss of their ability to roam the desert, primarily as the result of the imposition of state borders which in turn drew them into conflict with settled populations. Migration is in the heart of humans, we were a migratory species long before we became a settled one, which only happened 10,000 odd years ago with the advent of farming. Just the snap of a fingers in evolutionary terms. That act of settling, of claiming land, gave rise to new narratives, stories that staked people’s rights to the place they lived. People talk about roots, but plants have roots, not human beings. Humans have feet and feet are meant for walking. Now the world over migrating people are increasingly in conflict with settled people. When I find incuriosity in a person, it tells me that they already know everything they want to know. They’re worried they might hear something to contradict their view. They have their stories and they like them. I hope our enforced immobility will prompt a refreshed curiosity. People are already rediscovering their own locales. I film the animals that come into my own backyard. And so far I haven’t spoken to a soul who has said, I’m loving lockdown. I just want to stay indoors forever.

*

Maaza Mengiste was born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. A Fulbright Scholar and professor in the MFA in Creative Writing & Literary Translation programme at Queens College, she is the author of The Shadow King, a finalist for The Booker Prize. Her previous work, Beneath the Lion’s Gaze, was named one of Ten Best Contemporary African Books by The Guardian. Her work can be found in the New Yorker, Granta, and the New York Times among other publications. She lives in New York City.

Aminatta Forna’s essay collection The Window Seat is published in May 2021. She is also the author of the novels Happiness, The Hired Man, The Memory of Love, and Ancestor Stones, as well as the memoir The Devil That Danced on the Water. Forna’s books have been translated into twenty-two languages. She is the recipient of a Windham Campbell Award from Yale University and has been a finalist for the Neustadt Prize for Literature. Her essays have appeared in Brick, Freeman’s, Granta, The Guardian, The Kenyon Review, Lit Hub, The New York Review of Books Daily, The Observer, and Vogue. Forna is currently Director and Lannan Foundation Chair of Poetics at Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice at Georgetown University.

________________________________________

The Window Seat: Notes From a Life in Motion will be published by Grove Press in May 2021.