Allure and Illusions: My Seven-Year-Old, Me, and the Cult of Gymnastics

Alison Wisdom Finds Similarities Between an Elite Sport and a Fundamentalist Church

The world of gymnastics is a rigid one, each move dictated by rules, and gymnasts learn at an early age to follow those rules—this is not only how you stay safe while learning dangerous skills, but it’s how you score well at competitions, where deductions are taken for every single microscopic rule you break, every angle your body makes that’s too flat or too sharp, every flexed foot, every half-step out of line.

So when a girl becomes a gymnast, she isn’t just learning how to do a skill but how to do it correctly, how to perform it with the precision expected of her. And yet paradoxically, there is a freedom and ecstasy in the sport too: gymnasts do not seem bound by the same universal and physical laws the rest of us are, and when my daughter Margaux began gymnastics, it was like her world broadened. Suddenly, more things seemed possible than they previously had been.

But it is also true that the longer a girl continues in the gymnastics world, the more insular it becomes. As her abilities grow, a kind of narrowing happens. When Margaux was turning five and first starting to do gymnastics seriously, my husband and I watched an HBO documentary about Larry Nassar, and I realized that USA Gymnastics as an organization had failed its athletes, but the entire system had failed too, cultivating an environment that allowed something like this to happen.

These are girls like Margaux, who have spent their whole lives in the gym, whose bodies have done extraordinary things and suffered for them, who have had coaches’ hands on their backs and arms and legs, manipulating them, stretching them, training them, from the time they were four years old. They learn a connection between pain and success; when Margaux was six, she got her first rip—when the skin on a gymnast’s palm peels back and tears, a result of training on bars—and it was gnarly, but she was proud of it, showing it to everyone she saw. Finally, she was in pain, her body offering visual proof of what it took to improve. This was, to my daughter, a new achievement in her gymnastics life.

Illusions or not, the reverberations of belief are the same. And the scarier part of a cult? Sometimes you don’t know what you’re giving up until it’s already gone.

Then there’s the emotional strain. Once I read a profile of Aly Raisman in The New Yorker where she talked about the connection between a gymnast and her coach, her dependence on his approval. “If I take a turn and think I did a good job,” she says, “but my coach says I did a bad job, I’m going to think that what I felt was wrong.”

When I read this, my stomach clenched. I had seen this with Margaux already, who, whether she was succeeding or struggling, looked at her coach immediately to see his reaction: would he be proud? Disappointed? Was she bad at this? Once, on a water break, I told her what a good job she had done on beam, and she shook her head. “Coach says my pivot turns are sloppy,” she said.

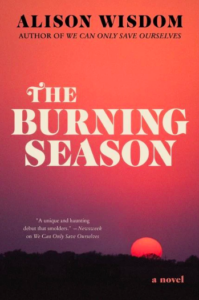

Around this time, I was writing my second novel, The Burning Season, about a woman named Rosemary who, in a final, desperate attempt to save her marriage, follows her husband to the ultra-conservative Church of Dawes. I struggled to understand Rosemary as a character, why she would end up in a place like Dawes, so I took stock of what I did know about her: she was a seeker, someone who wanted to feel things, not only spiritually but physically, a person who felt attracted to extremes, both desiring the comfort of rules and the thrill of breaking them.

I thought about Margaux, who always wants to jump as high and hard as she can, who wants to throw her body upside down, her curls hanging wild and loose. How she is a girl who knows how to listen, who wants to be good, to be better, to be as close to perfect as she can get. I realized that before she was a wife, before she was a member of the Church of Dawes, Rosemary was a gymnast.

So as I worked on my novel, I thought about gymnastics culture, the intensity of it, the rigidness. I thought about a singular coaching voice, how it could erode your sense of self. I thought about Simone Biles and Aly Raisman and the other young women abused by Larry Nassar and failed by USAG. I thought about my daughter. I thought about the hours we have spent in the gym. I thought of the way, in Margaux’s early months on the new team, I’d see girls crying as their coach knocked on their knees to lock them, pounded on their backs to straighten them, swatted at their legs to tighten them.

How he scolded the girls, shook his head in disgust when they didn’t do what he wanted. How, when he saw how worried I was, he assured me it wouldn’t be like this forever. “I have to be very tough on them at first so they know who the coach is,” he told me. He was right—it did get better, and Margaux and I both grew to love him. But there’s a tiny part of myself, clenching in shame, that wonders how I would have reacted had he never acknowledged my poorly hidden concern, if I would have just kept overlooking what made me uncomfortable because everyone else did, because that was what it would take for my daughter to be great.

As I worked on my novel, I thought about gymnastics culture, the intensity of it, the rigidness. I thought about a singular coaching voice, how it could erode your sense of self.

Similarly, Rosemary finds herself as a member of the fundamentalist Church of Dawes not because she truly believes in what they have to offer, but because she wants to save her marriage and wants to save herself, both miraculous desires. If she has to ignore some red flags for them to happen, so be it. After all, as a gymnast, she has grown up in a world that has demanded sacrifices of her; she is used to doing hard things. The gym is now her church, her coach’s voice is that of God or his proxies, the charismatic Papa Jake and her husband Paul. She trades one restrictive lifestyle for another, searching for purpose and structure, for something rigid to press against.

*

In a way, I feel like I have joined a cult too. It’s Margaux who’s enduring the hours of practice, whose hands bleed, who cries when she disappoints her coach, but I am the one watching and fixing buns and scheduling lessons and figuring out what she needs to work on, the one texting the other moms to organize group dinners, outings, ordering matching shirts for the girls. After practice, I debrief with my husband and tell him how Margaux did, if she struggled, if she had a good attitude, if she had fun; so far he has yet to respond with anything matching my level of interest. He is not in the cult.

But Margaux is in the cult because I am. Yes, we started doing this because she loves the sport, but one day she was tumbling around our house in a leotard with her panties visible through the gaping leg holes and the next I was applying three different kinds of product to her curly hair so her bun would be sleek, and I let it happen. All the things that make it this way have almost nothing to do with Margaux and everything with the adults who are responsible for Margaux: USAG, the coaches, the other parents. Me. The adults are the ones who put too much pressure on little girls, who make demands of their bodies and their brains and their hearts, who insist that gymnastics must be one of the top three things in their lives, second only to family and school. As a mother, this is a humbling realization.

But just like in the Church of Dawes, there are miracles in the gym too, things that make participation worth it. For Margaux, who is the one performing miracles, doing things she’s dreamed of, but for me too: It is a miracle to watch your child grow, to see her body and resolve strengthen. A miracle to witness the cavernous gym shrink around your daughter, until it as small and comfortable and familiar as her own home, a refuge from the looming world outside.

A miracle to watch the girls huddle around each other, how they touch each other’s backs so tenderly and grab each other’s hands so mindlessly, to hear them cheer their teammates on, amazing in a world that will eventually pit them against each other. To see girls fly through the air, propel themselves from bar to bar, tumble on an inches-wide beam is to experience the miraculous, their powerful bodies arcing, turning, twisting, doing impossible, beautiful things—and what is beauty if not a miracle?

Writing about a woman whose life is shaped by her past as a gymnast has made me more aware of my role as the mother of a little gymnast, as a person who is frankly a part of an organization demanding focus and devotion. This choice, my choice, is already influencing who Margaux is, and as in other areas of parenting, it’s hard to know when you’re doing the right thing or if you’re doing something that will reverberate down the line, into your child’s future, leaving them with trauma or pain or regret or resentment or, or, or.

And that’s part of it too, the fear that comes with being a parent. It’s a strange, scary world to be raising a child in, with so many things completely beyond our control. That anxiety is what can make a highly regulated lifestyle so appealing; this is why people find themselves in a cult—someone has promised they have the answers to life’s scary questions, and that’s more than a comfort.

At the gym, when the other parents and I talk about our daughters’ futures, imagine them as teenagers and all the accompanying mischief, we say, well, if they stay gymnasts, we’ll know where they are all the time: at the gym, training. No time for mischief, no room for trouble. This, of course, is illusory, and yet these things remain desirable, seductive. A cult, after all, always promises something better than what you have, as long as you do what they want, as long as you give something up—and that’s the scary part, isn’t it? Illusions or not, the reverberations of belief are the same. And the scarier part of a cult? Sometimes you don’t know what you’re giving up until it’s already gone.

_______________________________

The Burning Season by Alison Wisdom is available now via Harper Perennial.

Alison Wisdom

Born, raised, and based in Houston, Texas, Alison Wisdom has an MFA from the Vermont College of Fine Arts, received a novel-writing grant from Wedgwood Circle, and was a finalist for this year's Rona Jaffe Award. She has attended Tin House and the Lighthouse Writers Workshop, where she was a finalist for the Emerging Writers Fellowship. Alison's short stories have been published in Ploughshares, Electric Literature, The Rumpus, Indiana Review, and more. Her latest novel, The Burning Season, is now available.