Allen Ginsberg’s Definition of the Beat Generation

From the Poet's Lecture on How a Generation Got Its Name

To begin with, the phrase “Beat Generation” rose out of a specific conversation with Jack Kerouac and John Clellon Holmes in 1950-51 when discussing the nature of generations, recollecting the glamour of the “lost generation.” Kerouac discouraged the notion of a coherent “generation” and said, “Ah, this is nothing but a beat generation!” They discussed whether it was a “found” generation, which Kerouac sometimes referred to, or “angelic” generation, or various other epithets. But Kerouac waved away the question and said “beat generation!” not meaning to name the generation but to un-name it. John Clellon Holmes then wrote an article in late 1952 in the New York Times magazine section with the headline title of the article, “This is the Beat Generation.” And that caught on. Then Kerouac published anonymously a fragment of On the Road in New World Writing, a paperback anthology of the 1950s, called “Jazz of the Beat Generation,” and that caught on as a catchphrase, so that’s the history of the term.

Secondly, Herbert Huncke, author of The Evening Sun Turned Crimson, who was a friend of Kerouac, Burroughs, and others of that literary circle from the 1940s, introduced them to what was then known as “hip language.” In that context, the word “beat” is a carnival “subterranean,” subcultural term, a term much used in Times Square in the 1940s. “Man, I’m beat . . .” meaning without money and without a place to stay. Could also mean “in the winter cold, shoes full of blood walking on the snowbank docks waiting for a door in the East River to open up to a room full of steam heat . . .” Or, as in a conversation, “Would you like to go to the Bronx Zoo?” “Nah, man, I’m too beat, I was up all night.” So the original street usage meant exhausted, at the bottom of the world, looking up or out, sleepless, wide-eyed, perceptive, rejected by society, on your own, streetwise. Or, as it is now termed, fini in French, finished, undone, completed, in the dark night of the soul or the cloud of unknowing. “Open,” as in Whitmanic sense of “openness,” equivalent to humility, and so it was interpreted into various circles to mean both emptied out, exhausted, and at the same time wide open—perceptive and receptive to a vision.

Then a third meaning of the term, as later modified by Kerouac, considering the abuse of the term in the media—the term being interpreted as being beaten completely, without the aspect of humble or humility, or “beat” as the beat of drums and “the beat goes on,” which are all mistakes of interpretation or etymology. Kerouac, in various lectures, interviews, and essays, tried to indicate the correct sense of the word by pointing out the root—be-at—as in beatitude, or beatific. In his essay “Origins of the Beat Generation” Kerouac defined it so. This is an early definition in the popular culture, though a late definition in the subculture: he clarified his intention, which was “beat” as beatific, as in “dark night of the soul,” or “cloud of unknowing,” the necessary beatness of darkness that proceeds opening up to light, egolessness, giving room for religious illumination.

The fourth meaning that accumulated was “Beat Generation literary movement.” That was a group of friends who had worked together on poetry, prose, cultural conscience from the mid-1940s until the term became popular nationally in the late 50s. The group consisting of Kerouac; William Burroughs, author of Naked Lunch and other books; Herbert Huncke; John Clellon Holmes, author of Go, The Horn, and other books, including memoirs, and other cultural essays; Allen Ginsberg, myself, member of the American Institute of Arts and Letters since 1976; then Philip Lamantia met in 1948; Gregory Corso met in 1950; and Peter Orlovsky encountered in 1954; and several other personages not as well known as writers were in this circle, particularly Neal Cassady and Carl Solomon. Neal Cassady was writing at the time, [but] his works weren’t published until posthumously.

In the mid-1950s this smaller group, through natural affinities or modes of thought or literary style or planetary perspective, was augmented in friendship and literary endeavor by a number of writers in San Francisco, including Michael McClure, Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, Philip Lamantia, and a number of other lesser-known poets such as Jack Micheline, Ray Bremser, or the better-known black poet LeRoi Jones—all of whom accepted the term at one time or another, humorously or seriously, but sympathetically, and were included in a survey of Beat general manners, morals, and literature by Life magazine in a lead article in the late 1950s by one Paul O’Neil, and by the journalist Alfred Aronowitz in a large series on the Beat Generation in the New York Post.

Part of that literary circle, Kerouac, Whalen, Snyder, and, additionally, poet Lew Welch, Peter Orlovsky, Ginsberg, and others, were interested in meditation and Buddhism. The relationship between Buddhism and the Beat Generation can be found in a scholarly survey of the development of Buddhism in America, How the Swans Came to the Lake, by Rick Fields.

The fifth meaning of the phrase “Beat Generation” is the influence on the literary and artistic activities of poets, filmmakers, painters, and novelists who were working in concert in anthologies, publishing houses, independent filmmaking, and other media. The effect of the aforementioned groups—in film and still photography, Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie; in music, David Amram; in painting, Larry Rivers; in poetry and publishing, Don Allen, Barney Rosset, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti—extended to fellow artists; the bohemian culture, which was already a long tradition; to the youth movement of that day, which was also growing; and [to] the mass culture and middle-class culture of the late 1950s and early 1960s. These effects can be characterized in the following terms:

–general liberation: Sexual “Revolution” or “Liberation,” Gay Liberation, Black Liberation, Women’s Liberation too;

–liberation of the word from censorship;

–decriminalization of some of the laws against marijuana and other drugs;

–the evolution of rhythm and blues into rock and roll, and rock and roll into high art form, as evidenced by the Beatles, Bob Dylan, and other popular musicians who were influenced in the 1960s by the writings of Beat Generation poets and writers;

–the spread of ecological consciousness, emphasized by Gary Snyder;

–opposition to the military-industrial machine civilization, as emphasized in the works of Burroughs, Huncke, Ginsberg, and Kerouac;

–attention to what Kerouac called, after Spengler, “Second Religiousness” developing within an advanced civilization;

–respect for land and indigenous peoples as proclaimed by Kerouac in his slogan from On the Road, “The earth is an Indian”

The essence of the phrase “Beat Generation” can also be found in On the Road in another celebrated phrase, “Everything belongs to me because I am poor.”

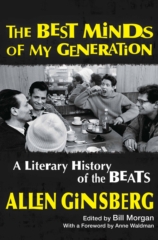

From The Best Minds of My Generation: A Literary History of the Beats, Allen Ginsberg, edited by Bill Morgan.