Telling Stories of Police Brutality, One Panel at a Time

For Dan Méndez Moore, Labor Justice is Racial Justice

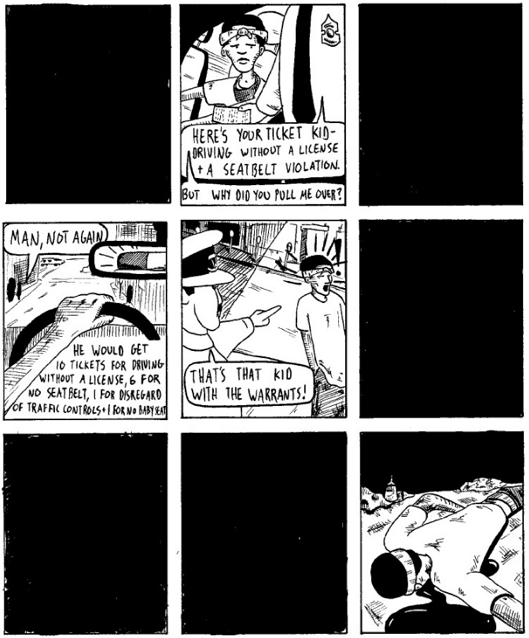

It’s an all-too-familiar story now, but it was less so at the time. On April 7, 2001, Cincinnati police attempted to arrest 19-year-old Timothy Thomas. Thomas had been pulled over a number of times in the previous months, and issued with a string of traffic citations for not wearing his seatbelt and driving without a license. On April 7, after Thomas attempted to evade escape, he was shot dead. He was unarmed.

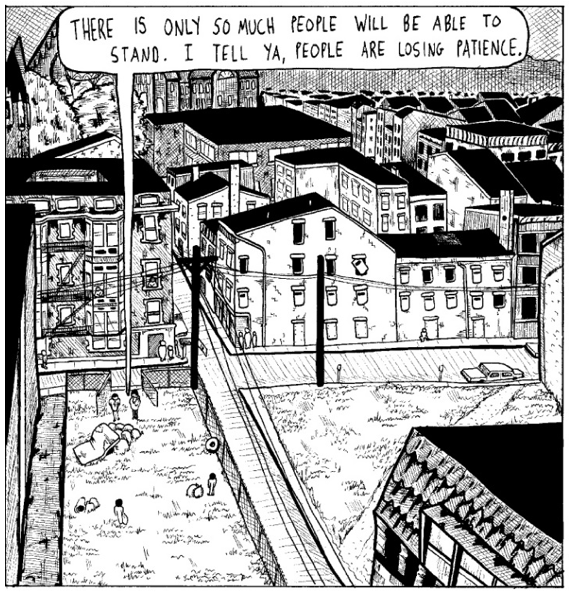

The Cincinnati neighborhood of Over-the-Rhine erupted afterward. But a word like “erupted” doesn’t do justice to structural conditions like high poverty and unemployment in the neighborhood, or to the long-simmering racial tension that had led to multiple police killings of unarmed black men long before Thomas’ death.

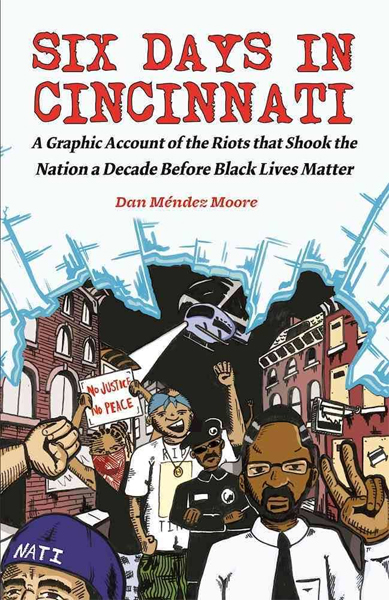

The protests that followed Thomas’ killing are documented in Dan Méndez Moore’s Six Days in Cincinnati: A Graphic Account of the Riots That Shook the Nation a Decade Before Black Lives Matter.

The protests in general were “a foundational moment” for Moore, as “these events helped center for me the role of racial justice organizing in anything that I work on.” He was an idealistic 17-year-old at the time, who’d recently started a group called Cincinnati Radical Youth (yes, CRY), which focused in the early days on distant-seeming issues like free trade. The uproar around the continued police killings of black men in his own city prompted him to confront his own biases and privileges. And it “changed my naïve perspective of seeing the black community as victims, to seeing the black community and people in general as protagonists.” It’s a principle he holds on to as a union organizer today: “If we treat people as wounded victims, that’s not a way to create change.”

Six Days in Cincinnati, forthcoming in June, reports on this period that’s well-remembered in Cincinnati but largely forgotten outside of Ohio. It collects testimony from people with strong memories of the time: activists like Robert Pace, who recounts resistance to police suppression of protest; members of the clergy like Reverend Damon Lynch III, who reflects on tactical mistakes in activism; and Mrs. Keith, a teacher who talks about how Over-the-Rhine has changed over the years.

This isn’t a straightforward journalistic account, though. For one thing, Six Days in Cincinnati is told in graphic memoir form. Moore chose this medium partly because the upheaval in 2001 was itself so visceral, which lent itself to visual storytelling. At the same time, he recognizes that Cincinnati is under-appreciated. He wanted to capture the unexpected beauty of the city, from its housing units to its public buildings. He also wanted the book, which aimed to be “decent people’s history,” to look like something a teenager might conceivably pick up.

The book also isn’t traditionally journalistic in that Moore doesn’t pretend to be an objective observer. He’s keenly aware of the limitations, as well as advantages, of his own perspective. He refers to his whiteness as “the elephant in the room” when it comes to many situations, from organizing the union activity of predominantly non-white low-wage workers, to writing a book about riots sparked by continuous racial injustice. “I would be a fool to approach any situation without an understanding of how people see me and my own biases,” he says. His strategy is to be up-front about his position and privilege—relatively easy to do in a comic book where visuals can reveal certain information about identity in an instant.

The decision to insert himself into the book was influenced by the work of a landmark comics journalist, Joe Sacco, who has reported from conflict zones in Palestine and the former Yugoslavia. “He does a great job of placing himself as a journalist in the story” without making the story about him, Moore says of Sacco. This acknowledges the way a story is reported, which can sometimes be as revealing as the actual content itself.

Moore’s self-portrait in Six Days in Cincinnati is self-deprecating in a manner similar to Sacco’s portrayal of himself: inquisitive and slightly goofy, permanently wearing a skull T-shirt that emphasizes the divergence between a naïve white kid asking questions and the impassioned black residents speaking about a matter that’s literally life and death for them.

What Moore has tried to do with the book is to “create a tapestry of different people who were involved in the movement.” Moore draws not only what he saw, such as the heavy-handed enforcement of the post-riot curfew in predominantly black neighborhoods, compared to the blithe disregard of the curfew in largely white areas. He also depicts different interviewees’ actions at the time and their comments afterward.

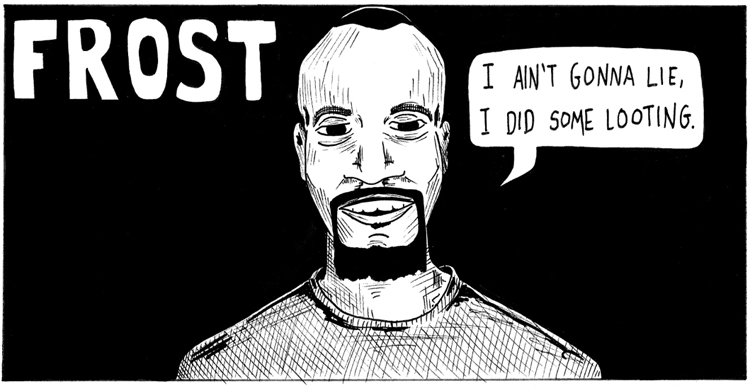

One of the most interesting interviewees is Frost, who was an assistant manager at a car repair shop during the protests. Frost echoes a sentiment that’s expressed by other people in the book: that the looting that accompanied the protesting wasn’t just frivolous or materialistic; it was a deliberate protest tactic chosen because traditional channels of activism weren’t working. It wasn’t until property damage entered the picture that the outside world really started paying attention. Frost says, “It really was about the message. The jackets + stuff were like . . . eh . . . a fringe benefit.”

As Moore says, “on a tactical level I think the riots bring up an ongoing argument of the role and effectiveness of disruption, property destruction, and violence in protest movements . . . there is no doubt that the escalating nature of the protests completely changed who was at the decision-making table.”

This was clear, for instance, in the example of the reverend who prior to the rioting and property damage had been seen as an extreme leftist, but following the violence had a new legitimacy. City leaders were suddenly seeking him out as an apparently moderate voice.

Moore now lives in Minneapolis, where he works as an organizer for SEIU Local 26, a union of janitors, retail security officers, and other low-wage service workers. Specifically, he works with these employees to advocate for better working and economic conditions. He says that union members, who are predominantly Latino, with significant proportions of Somalis, Ethiopians, and African-Americans, are very aware that they’re treated differently by law enforcement. “People do or don’t answer their doors depending on the political environment . . . People don’t come to protest in part because they’re afraid.” Protests involving ethnic minorities with a lot at stake often have to be more organized, more careful, than protests of white people, who tend to be perceived as non-threatening.

Despite the fact that a book about 2001 protests of police brutality remain searingly relevant today, Moore—now married and with an infant who limits the time he can spend drawing narrative comics—holds on to hope. He says in his half-joking, half-serious manner, “We can’t afford to be pessimistic, and really white people have no excuse to be pessimistic.”

There’s been some debate lately over whether objectivity in journalism and biography is really something to be prized—and indeed whether it’s even possible. In an era when Black Lives Matter remains somehow a controversial name, and attacks on civil liberties are relentless, a peculiar little sub-sub-genre like comics journalism is as relevant as it’s ever been. Because comics, which take so punishingly long to produce, have long tended toward biography and memoir; if a cartoonist is going to spend many years on a single work, often the most rewarding subject matter is, well, themselves or the real world. With no end to police violence in sight, a work like Six Days in Cincinnati makes both an appropriate fit for the genre and the modern day.

All images © 2017 by Dan Méndez Moore.