All the fake books in Wes Anderson's multiverse, ranked.

This week, Wes Anderson’s latest concoction, The Phoenician Scheme, hits screens. And thanks to this latest work from a pointillist who loves his reference texts, I’m thinking about Anderson’s prop books.

Wes has romanticized the literary arts for almost his whole career. His Salinger obsession shows in The Royal Tenenbaums, which owes something to Franny and Zooey. The Grand Budapest Hotel was openly inspired by Austrian writer Stefan Zweig’s The Society of the Crossed Keys. And Jacques Cousteau’s Diving for Sunken Treasure fueled oceanic obsession in both Max Fischer (of Rushmore) and Steve Zissou (of, The Life Aquatic).

All of this can account for the growing syllabus of novels, non-fiction, and plays to be found in Anderson’s own canon. Of course, not all homages are created equal. So here’s a ranked list of the (best) books in the Wes-iverse.

Read ’em, then scheme.

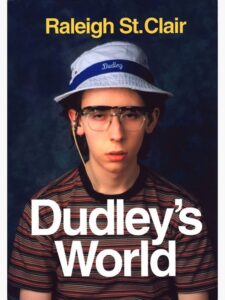

12. Raleigh St. Clair, Dudley’s World

I have methodology questions about this wander-y pop-psych project, examining a young boy’s mysterious medical condition. (Its vague entry-point resembles that of St. Clair’s previous work, The Peculiar Neurodegenerative Inhabitants of Kazawa Atoll.) We never get a sense of the why, the how, or the what-to-do about Dudley. Just a lot of othering description.

St. Clair’s lengthy digressions also convey a real scorn for his poor subject. I mean, mocking the hat? It strains medical ethics.

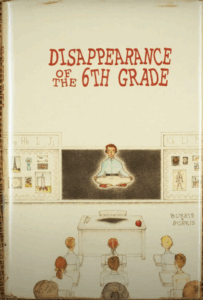

11. Burris & Burris, Disappearance of The Sixth Grade

This Kafkaesque take on public education sort of talks to Louis Sachar’s (real) Sideways Stories from Wayside School. But this allegedly YA property is far headier. So heady, in fact, that this adult got lost in the metaphor. Neither Burris clarifies whether its the class or the construct that has, finally, “disappeared.”

10. Eli Cash, Old Custer

On its release, most critics disparaged this bloated historical effort from the love (and dope-)sick Eli Cash. Consensus went out of its way to call this posturing Neo-Cowboy, who struggled to place himself somewhere in the McMurtry-McCarthy-Stegner idiom, “not a genius.”

But I’m a simple woman, and a sucker for a clear log-line. After all, everyone already knows Custer died at Little Bighorn. The revisionist presupposition that “maybe he didn’t” is drama, defined.

9. Max Fischer, Heaven and Hell

Though certainly an improvement on his freshman (year) effort—a watery, unofficial adaptation of Peter Maas’ Serpico—Heaven and Hell does suffer from cliche. The high-octane war thriller is fun to imagine staged, but dialogue tends to be overwrought. Especially in the predictable denouement.

(But I note this is just one student journalist’s opinion.)

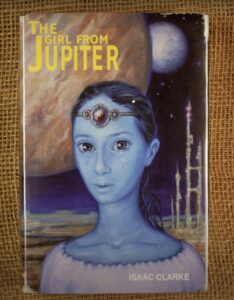

8. Isaac Clarke, The Girl From Jupiter

Is this one a little derivative of a lesser Asimov? Sure! But the art work in this sci-fi spec about a stranded Jupiterian is truly gasp-worthy. Definitely would take in my runaway’s suitcase.

7. Etheline Tenenbaum, Family of Geniuses

This boastful survey is, on the one hand, very readable. The prose describing this unusual but compelling family dynamic is clipped and clarion. And in the end, I do buy Tenenbaum’s argument. These kids are pretty talented.

That said, one gets the sense that the author is missing something key by failing to capture any of the children’s interiority.

6. Gertrude Price, The Francine Odysseys

A personal favorite, this out-of-print gem captures the unique poignance of an inter-species friendship with grace and gravitas. Would also take in my runaway’s suitcase.

5. Edited by Arthur Howitzer Jr., A Hundred French Dispatches: An Anthology

Including world-class reporting from the likes of New Journalist superstars Lucinda Krementz, J.K.L. Berenson, and Roebuck Wright, this rangy anthology is a must-have for any serious magazine fan.

But some of the pieces here collected stand the test of time better than others. My favorite contributions in this dense but rewarding doorstop are from Wright. Krementz’s glib observations on a nascent counter-culture (“Revisions to a Manifesto”) may come off dismissive to a modern revolutionary.

4. Henry Sherman, Accounting for Everything

Full of extraordinarily practical advice, this handy handbook may not be the most gripping read, but it will put your messy house in order. In Mr. Sherman’s capable hands, I got a warm fuzzy feeling of safety. Like every promise would be kept, every trouble washed away.

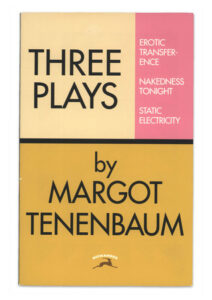

3. Margot Tenenbaum, Three Plays

By turns visceral and acidic, these dramas explore tamped yearning and the cost of thwarted lust. I note a curious contrast here between creator and creation. The dialogue in Erotic Transference is as bloody as the author—a notoriously eccentric recluse—is dry.

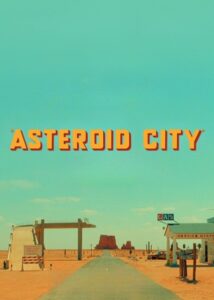

2. Conrad Earp, Asteroid City

Of the three dramatists on this list, Earp is obviously the most developed. This later work from an American hero is a confidently strange, surrealist puzzle-box, and stands in sharp contrast to the maestro’s early melodramas. Is it a bird, is it a plane? A book? Or a television special? These questions fuel a narrative that puts a “post” before modern.

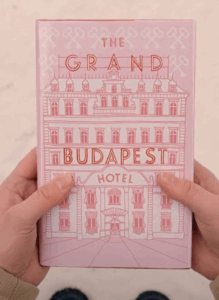

- Our National Treasure, The Grand Budapest Hotel

This beautifully told, closely observed chronicle of an “elegant old ruin” captures a bygone old world. The prose is lush, the characters are compelling, and all the attention to detail is on point. May be the best banana in the bunch.

(P.S. More on the Moonrise titles can be found here.)

Brittany Allen

Brittany K. Allen is a writer and actor living in Brooklyn.