Elfrieda is so thin, her face so pale, that when she opens her eyes it is like a surprise attack, like one of those air raids that turns night to day. I ask her if she remembers that time she and I sang a really slow aching version of “Wild Horses” for a group of elderly Mennonite nursing home residents. Our mother had asked us to participate in the seventy-fifth wedding celebration of the town’s oldest married couple and we had thought the song was killer cool and entirely appropriate for the occasion. Elf played it on the piano and I sat next to her and we both sang our hearts out to our bewildered audience who sat around in wheelchairs or stood leaning hard on canes and walkers.

I thought the memory would make her laugh but it makes her ask me to leave. She realized before I even did that I was spinning out this anecdote because it represented something else and more than the sum of its parts. Yoli, she says, I know what you’re doing.

I promise I won’t talk about the past if it causes her pain. I won’t talk about anything if she doesn’t want me to, as long as I can stay.

Please go now, she says.

I tell her I could read to her the way she used to read to me when I was sick. She would read Shelley and Blake, her poet lovers she called them, mimicking their voices, male and British, clearing her throat… “Stanzas Written in Dejection, near Naples.” The sun is warm, the sky is clear, the waves are dancing fast and bright. How about I sing? Or I could dance. Like a wave. I could whistle. I could do impersonations. I could stand on my head. I could read Heidegger’s Being and Time to her. In German. Anything! What’s that thing again, that word?

Dasein, whispers Elf. She half smiles. Being there.

Yeah, that! Please! I sit down and then stand up again. C’mon, I say. You like books with being in the title, don’t you? Please. I sit down next to her again and then put my head on her stomach. What was that quote on your wall? I ask.

What quote? she says.

On your bedroom wall, when we were kids.

You put the fist in pacifist?

No, no… that other one, about time. Something about the horizon of being.

Be careful, she says.

The piano?

Yes. She puts her hands gently on my head and keeps them there as though she is resting them on a pregnant belly. I can feel their heat. I hear her stomach rumble. I smell the Ivory Snow scent of her T-shirt that she has on inside out. She massages my temples and then pushes me off her. She says she doesn’t remember the quote. She tells me that time is a force and we must allow it to do its work, must respect its power. I consider arguing that she herself is disrespecting that power by attempting to sidestep it but then realize she might already have made note of that and is talking to herself as much as she is talking to me. There is nothing to add. I hear her whisper yet another apology and I begin to hum a Beatles song about love and need.

Remember Caitlin Thomas? I say.

Elf says nothing.

And remember how she barged drunkenly into Dylan’s hospital room at St. Vincent’s in New York City where he was dying of alcohol poisoning and threw herself on top of his beleaguered body begging him to stay, goading him to fight, to be a man, to love her, to speak, to stand, to stop dying for god’s sake. My sister says she appreciates being compared to Dylan Thomas but apologizes and asks me again to leave, she needs to think. I tell her all right, I’ll leave but I’ll be back tomorrow. She says isn’t it funny how every second, every minute, every day, month, year, is accounted for, capable of being named—when time, or life, is so unwieldy, so intangible and slippery? This makes her feel compassion toward the people who invented the concept of “telling time.” How hopeful, she says. How beautifully futile. How perfectly human.

But Elf, I say, just because you have no use for the systems that help us measure our lives doesn’t mean that our lives don’t need measuring.

Maybe, she says, but not according to some bourgeois notion of time compartments. That’s a fascistic arrangement of a thing— time—that’s naturally and importantly outside the realm of categorization or even definition.

Actually, I am okay with leaving right now after all, I say. Sorry to have to leave class early, Professor Pinhead, but I’m running out of time on my meter. I bought two hours and I think they’re up. Speaking of time.

I knew I could get you to leave, she says. And we hug and I begin to tell her that I love her before words become impossible and we simply breathe together in each other’s arms for a minute, before I go. Before I have to be elsewhere.

* * * *

I check my messages while I descend the hospital stairs two by two to the exit. A text from Nora, my fourteen-year-old: How’s Elf??????????????????????? Will broke the front door. And another from Will, my eighteen-year-old son who’s in his first year at NYU but whom I’ve commandeered to stay with Nora for a few days in Toronto while I am back in Muddy Waters: Nora told me her curfew is four am. True? Give Elf a hug from me! The shower drain is plugged from N’s hair. And a text from my oldest friend, Julie, who is expecting to see me later that evening: Red or white? Give my love to Elfie. xo

* * * *

The last time my sister tried to kill herself was by slowly evaporating into space. It was a furtive attempt to disappear by starving herself to death. My mom phoned me in Toronto and told me that Elf wasn’t eating and she was begging her and Nic not to call a doctor. They were desperate. Would I come? I went directly from the airport to Elf’s bedroom and knelt by her side. She asked me what I was doing there. I told her I was there to call a doctor. Mom might have made a promise not to call a doctor but I hadn’t. Our mother stayed in the dining room. She had her back to us. She couldn’t support one daughter’s idea over the other daughter’s idea, like any good mother, so she removed herself from the proceedings. I’m calling, I said. I’m sorry. Elf pleaded with me not to. She implored me. She put her hands together in supplication and begged. She promised to eat. Our mother stayed sitting at the dining room table. I told Elf the ambulance was on its way. The screen door was open and we could smell the lilacs. I won’t go, said Elf. You have to, I said. She called to our mom. Please tell her I won’t go. Our mother said nothing. She didn’t turn around. Please, said Elf. Please! She used what little strength she had left to give me the finger as the paramedics loaded her into the back of the ambulance.

That was the first time I met Janice. I had been standing next to Elf’s stretcher in the emergency room. Her broken backpack hung on the IV unit next to her. I was sliding my hands back and forth on the steel railing that held her in and I was crying. Elf took my hand, weakly, like an old dying person, and looked deeply into my eyes.

Yoli, she said, I hate you.

I bent to kiss her and whispered that I knew that, I was aware of it. I hate you too, I said.

It was the first time that we had sort of articulated our major problem. She wanted to die and I wanted her to live and we were enemies who loved each other. We held each other tenderly, awkwardly, because she was in a bed attached to things.

Janice—she had that furry creature hanging from her belt loop even then—tapped me on the shoulder and asked if she could talk to me for a minute. I told Elf I’d be right back and Janice and I walked over to a little beige family room and she passed me a box of Kleenex and told me that I had done the right thing by calling the ambulance and that Elf didn’t really hate me. That feeling can be broken down, she said. Right? Let’s consider the components. She hates that you saved her life. I know, I said, but thanks. Janice hugged me. A close, hard hug from a stranger is a potent thing. She left me alone in the beige room. I tore away at my fingernails and cuticles until I bled.

When I went back to Elf she was still in Emergency. She told me she’d just overheard a great line, just great. What was it? I asked her. She quoted: We are very much amazed at what little intelligence there is to be found in Ms. Von R. Who said that? I asked her. She pointed at a doctor who was scribbling something at the circular desk in the middle of all the dying people. He was dressed like a ten-year-old in skater shorts and an oversize T-shirt like he’d just come from an audition for Degrassi High. Who the hell did he say that to? I asked. That other nurse, said Elf. He figures that because I’m not grateful for having my life saved I must be stupid. Asshole, I said, did he talk to you? Yeah, sort of, said Elf, it was more of an interrogation. C’mon Yolandi, you know how they are.

Equating intelligence with the desire to live?

Yeah, she said, or decency.

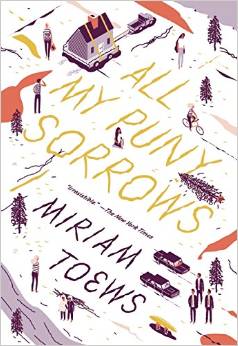

Head here for a chance to win a copy of All My Puny Sorrows.

From ALL MY PUNY SORROWS. Used with permission of McSweeneys. Copyright © 2015 by Miriam Toews.