All Hail the Beaver, Mighty Linchpin of the Natural World

Ben Goldfarb and Derek Gow Have the Conversation You Didn't Know You Needed

The beaver—yes, really, the beaver—is Animalia’s most generous member. By building woody dams and engineering ponds, beavers furnish habitats for just about every creature that flies, walks, and swims in North America and Europe; scientists thus refer to the rodent as a keystone species, an animal that sustains entire ecosystems.

A visitor to a prehistoric beaver pond in Britain, writes Derek Gow in his delightful new book, Bringing Back the Beaver, would have experienced nature at its most exuberant: moose, wolves, otters, frogs, fish, all overseen by the “(s)olemn sentinels of the black storks in the leaf dim gaps on the limbs of the high trees.”

Gow, stout and whiskery, bears a passing resemblance to a beaver himself,and he’s just as industrious. He’s a hard man to categorize: He’s a biologist, an animal breeder, a farmer; in his youth, he emceed agricultural auctions. These days, he is most renowned for his beaver boosterism. Several hundred years ago, beavers vanished from the British Isles, hunted to extinction for their meat, pelts, and scent glands, which were purported to have medicinal properties. Since the mid-1990s, Gow has spearheaded the movement to reintroduce the species—in the process, defying recalcitrant bureaucrats and occasionally the law itself. Bringing Back the Beaver is the unvarnished story of his improbable triumph.

In 2017, while researching my own book, Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter, I visited Gow at Upcott Grange, his farm in Southwest England, where he breeds and husbands beavers, water voles, polecats, and other rare critters. The trip was memorable not merely because one of his beavers nipped me on the ankle, but because Gow himself is an enchanting conversationalist: eloquent, profane, hilarious, and overflowing with ecological knowledge.

So I was thrilled to reconnect with Britain’s foremost Beaver Believer to discuss his new book. “I’m sitting at the top of a hill, in the car, watching a bunch of cows,” Gow told me over a recent Zoom call. “It’s raining, and it feels like December. It’s a typical British summer.”

*

Ben Goldfarb: We’re speaking at a curious time: In the wider world, of course, the news is relentlessly negative, but in the niche community of beaver advocacy, it’s a landmark month. Just last week, the British government officially permitted beavers to remain in the River Otter (yes, it’s a confusing name)—“the first legally sanctioned reintroduction of an extinct native mammal” in England’s history, per the Guardian. How did Britain get to this moment, that the beaver’s legal status was at last resolved in your favor?

Derek Gow: From a planetary point of view, we all know how sick the earth is. We all know that nature is hemorrhaging in a way we never believed possible. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, believe you me, is here now. People are finally thinking differently about what the countryside is for, about the fact that everything doesn’t always have to be intensive agriculture, that we can make space for this life-giving rodent. We have failed so many times on the beaver issue, but we were beginning to grow tiny green tendrils of hope. It’s astounding to see the kind of cheerleading that goes on for the species now.

You know, some of the best things that have happened are when the government has basically said, we’re going to kill them. When the people who care about beavers are given a chance to actually use their own voice, they say no, that’s not the way it’s going to be—this animal deserves to be here.

“I think beavers are about restoring a lost natural process in a cultural landscape that can easily bear their return with a degree of intellectual readjustment.”

That’s how it happened on the River Otter, and that’s how it happened on the Tay [a Scottish river where beavers were also mysteriously reintroduced and permitted to remain, though they’re still frequently killed by irate farmers]. The last bastion of dark ignorance will be in Wales, where the government there is assembling itself to deal with a small population of beavers in the River Dyfi. I’m quite sure the outcome will again be the same.

BG: The return of beavers is perhaps the most prominent example of rewilding, an idea that seems to have captured the imagination of Europe’s conservation community. The word “rewilding” isn’t really in widespread use in the United States, and it strikes me as kind of a protean, malleable concept—I’ve heard people use it to describe everything from species reintroduction to simply letting the weeds grow in your backyard. What does rewilding mean to you, and where do beavers fit in?

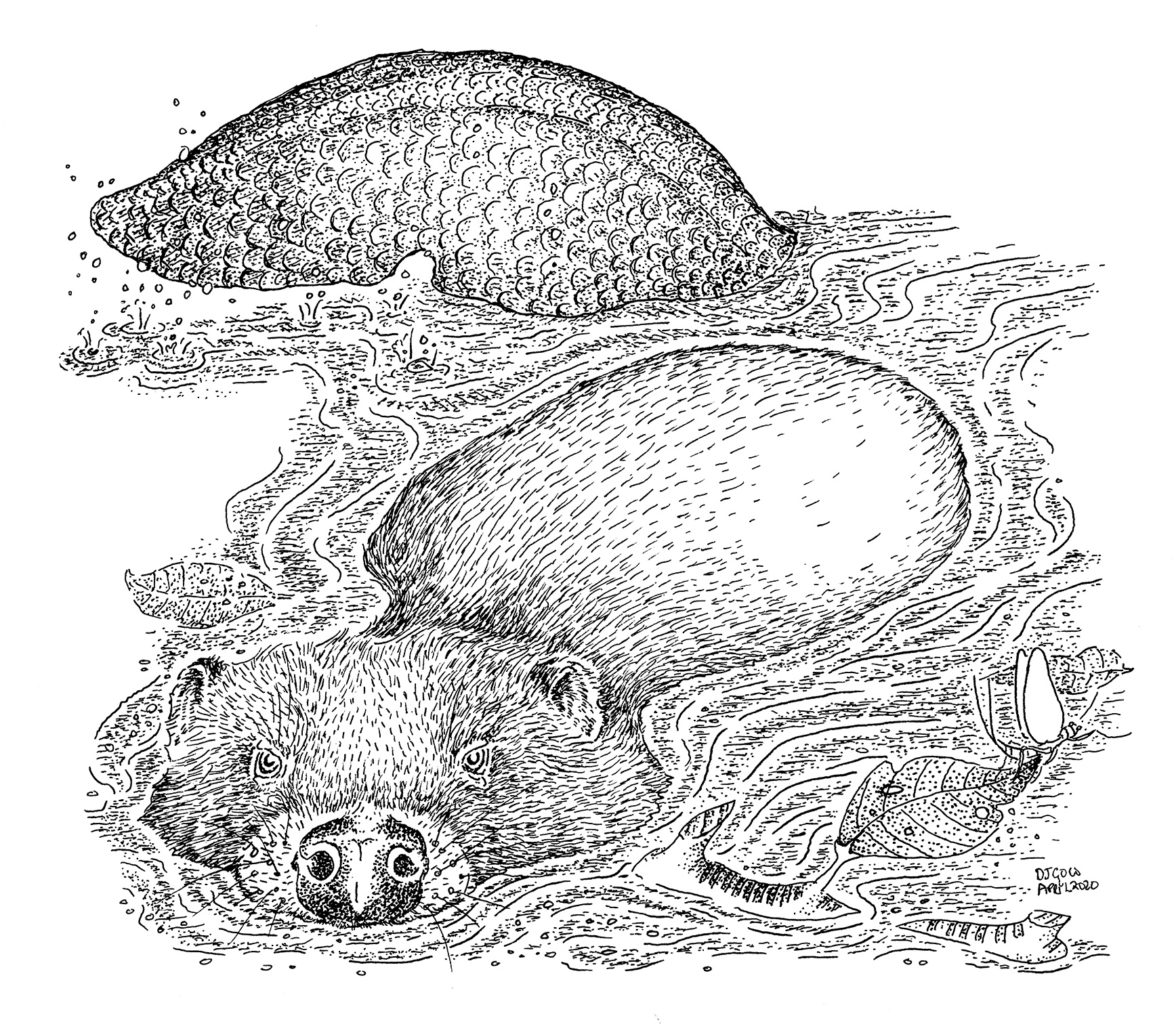

Illustration by Derek Gow

Illustration by Derek Gow

DG: Rewilding to me is almost a false god or prophet. I think you’re right when you say it can mean anything. I really have no interest in the term. You’re probably aware that one of the political parties that historically talked about rewilding was the Nazis. People like Goering and Himmler wanted to return half of Poland to a hunting reserve, and the word they used for it was rewilding.

For me, I wouldn’t think beavers have anything to do with that. I think beavers are about restoring a lost natural process in a cultural landscape that can easily bear their return with a degree of intellectual readjustment.

What it’s really about is how we remake nature. And that’s going to mean giving it space, taking land back from farming, creating corridors on the landscape that carry nature through. A lot of people are looking, I think, at life again, and questioning what it’s all about, and what their own individual purpose is.

And some of them are acting on it—they’re buying land, and saying, actually, we’re not going to farm any of this. We’re going to take ryegrass pastures and reseed them with wildflowers. There’s almost a belief system forming about it, but it’s not cohesive yet.

Once we get that physical part right, it’s down to how we adjust what’s in our hearts as well. Because as you in North America know full well, there is no bottom to the depths of darkness that governs how we treat species like wolves, in your case, or badgers here, which we’re culling because we blame them for bovine tuberculosis.

If we can’t address these two things—the idea that we’re going to have to give other creatures space to live on this planet, and that we’re going to have to make some serious effort to tolerate their behaviors, their whims, their needs and requirements—then there’s going to be no future for anything on this planet at all, other than us. And we will not last long.

BG: It’s interesting you mentioned wolves, because—

DG: Sorry, I’m just about to run over a cow because it’s eating the car.

BG: Pardon?

DG: If there’s any salt on the cars, they’ll start by licking it, and then they’ll actually start to rip the paintwork off. So you know all that stuff I said about tolerance and understanding? If that cow touches the bottom of this truck with its teeth, I’m gonna run over its head. If there’s a lot of screaming in a minute you’ll know what’s happened.

BG: Should I carry on? Is the cow crisis averted?

DG: Yes, carry on. We’ll just ignore the buggers.

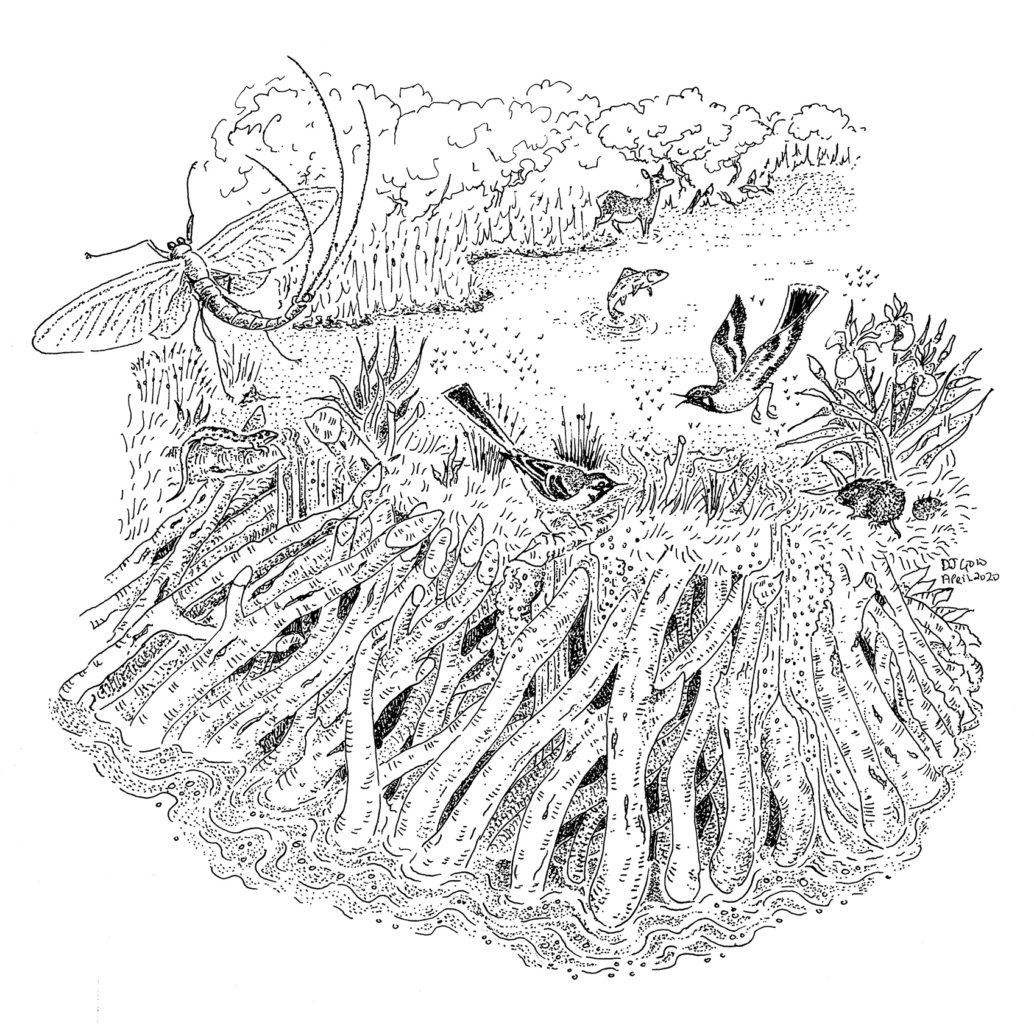

Illustration by Derek Gow

Illustration by Derek Gow

BG: Okay, cows aside: it’s interesting that you mentioned wolves a moment ago. One of the things that struck me during my time in the UK—and something that you helped open my eyes to—is how domesticated your country is compared to ours. Even British national parks have sheep on them.

Here in the United States, of course, we’ve obviously done more than our fair share of screwing up nature, but we’re still fortunate to have wolves and bears and moose and beavers. I think Americans take our biodiversity for granted. How do our two landscapes—and, more important, how we perceive our landscapes—compare to you?

DG: You’ve got to bear in mind that you guys have only got several hundred years of colonial history. We’ve been on this very small island smashing things up ever since we could stand up on our two hind legs. If you speak to archaeologists, they will tell you as soon as you get to the Bronze Age, things like the beaver disappear pretty damn quickly after that.

“We take an animal and smash and kill and destroy it, and quantify none of it.”

Look at landscapes not only in Britain, but the world over—look at North Africa, look at Morocco. Once, you had a landscape where animals from Africa met animals from Eurasia; you had cedar forests with hartebeest and Atlas lions, bears, wild boar, red deer. You had these continental clashes of different groups of animals that we now perceive to be from different parts of the world. You go look at it now and there’s virtually nothing left alive, or nothing compared to historically what they used to have.

So when it comes to your landscapes, I think that, yes, you are blessed. Of course, now you look at all the terrible things happening under the Trump administration—the deregulation and the smashing-up of the intellectual cores that were pretty integral in institutions like the National Park Service, systems of thought and belief that seemed to flow through administrations without becoming very political. Christ knows the longer term implications of that.

I’m just actually in the process of starting a book about the history of the wolf in Britain. The long and short of it is that we take an animal and smash and kill and destroy it, and quantify none of it. It’s just something we are sacrificing to appease the great god of greed that motivates parts of our society. You’ve got to be in a big upper before you start thinking about this stuff, because by the time you finish, you’re going into some depths of horror.

BG: Now that we’re sufficiently depressed, I wanted to change tacks a bit. One of the things that delighted me about Bringing Back the Beaver was its contempt for bureaucracy. You’ve waged this multi-decade war against overly cautious officials and the ignorant landed gentry, and you have no love lost for any of those people.

Beavers almost seem like a form of resistance—you describe them as “totems of change” and “a challenge to the hegemony.” Speaking of the Trump administration, what has your time in the beaver trenches taught you about navigating and resisting a willfully stupid government with no interest in science-based policymaking?

Illustration by Derek Gow

Illustration by Derek Gow

DG: It’s taught me to make my own mind up. When I started to work in nature conservation, like most young people, I believed that other people acted in good faith. I believed that you could sit down and have your stakeholder meetings and you would make progress based on facts, on science, on thought, on a collaborative willingness to do good. And as you get older, you realize that that’s just not the way of it.

You’ve got to be prepared to stand up for what you think is right. For me, the beaver thing was always very clear. I’ve talked to some of the old guys who tried and failed to reintroduce beavers many years ago, and they’d tell me how near they’d come to succeeding. And then this wee wanker of a civil servant—one of these people who are employed not to rock the boat—just said no.

Any kind of bureaucracy is there to maintain a status quo, and it attracts people who operate like molerats, and they don’t want to have any other molerat in that colony digging a tunnel in the direction that’s opposite to the ones that the molerats have already agreed is the right direction—even if that means digging no tunnels at all. In the end, you just get to the stage when you say, you know, it’s enough. It’s just enough.

You only lose if you play by the stupid rules that stupid people have made. I never meant to become such a rallying figure of opposition, but I don’t want to be lying in a bed at the end, regretting the things I didn’t do. And I don’t consider the people who oppose doing the right thing to be worthy of any sort of reverential respect. I want to be on nobody’s Christmas card list.

BG: I don’t think you need to worry about that, Derek. The beaver universe is full of colorful characters—you’ve probably got to be a bit eccentric to fall in love with a semiaquatic rodent—but you have an especially interesting biography. In addition to being a farmer and a biologist, you’re also an artist, and a big part of the experience of reading this book is your illustrations of beavers and other animals. They’re both meticulously detailed and whimsical, at once realistic and charming. What role does art fill in your work?

DG: That’s actually quite a good description, although I have to say that I’ve become much more content with my illustration and drawing style over time. I have the ability to draw in a scientifically exact fashion, but there just doesn’t seem to be a lot of personality in it. When it comes to illustrations, I want to give animals almost an individual personality, so that they’re not just innumerable automatons.

Without being hugely anthropomorphic about it, here I am, sitting up on a hill surrounded by cows, and they’re all characters. We very commonly fail to realize that animals are individuals.

“They talk to their babies as they wake up—they uncurl slowly, murmuring and mewing to each other. That’s what they’re like.”

When I was little, I never really questioned anything. The old guys I knew—my relatives, or the ones I worked for—they would tell me that you had to slaughter every raven you could find because they pecked the lambs, and I never thought about it twice. We think about animals as though they’re just anonymous, and I have to say I detest that.

I don’t enjoy killing anything anymore. I don’t have a rifle, I don’t shoot. I have seen more than enough death in this life and I have no wish to impose any more on anything else unless there is a very, very good reason for it. Sometimes you have to smack a sick chicken on the head because there’s no point going on with it, and it doesn’t move me particularly, but it’s always with a degree of regret.

Illustration by Derek Gow

Illustration by Derek Gow

BG: Your answer anticipates my last question. You’ve spent more time with beavers than anybody else in Britain, and in your writing you’re not shy about imbuing them with personality and intelligence. You describe beavers as possessing love and warmth, and you mention that they use language with their kits, which seems like a very deliberate word choice. In the beaver world, we talk a lot about how wonderful the species is, but we don’t talk much about beavers as individuals. So, Derek: What are beavers like when you really get to know them?

DG: Well, you get some that are real shits. I never have met the Donald Trump of the beaver world, but there were some that were really horrible. There was one particular family that came from Bavaria [where most of the beavers reintroduced to Britain originate] and they were just all bloody aggressive. We could never pair them with anything because they always tried to kill whatever you gave them.

But in the main you’re looking at animals that are just delightful. We had one tame one that, if you went past pretty much any time of the day, would come out to see what you were doing. You could sit in there, you could pat the ground with the palm of your hand like you play with a puppy, and it would bounce over and make gurgling noises.

The bulk of them are benign, they’re calm, they’re careful. They talk to their babies as they wake up—they uncurl slowly, murmuring and mewing to each other. That’s what they’re like. These animals are deeply sentient, deeply caring. And that’s why I detest the barbarity.

__________________________________

Derek Gow’s Bringing Back the Beaver is available now.

Derek Gow and Ben Goldfarb

Derek Gow is a farmer and nature conservationist. Born in Dundee in 1965, he left school when he was 17 and worked in agriculture for five years. Inspired by the writing of Gerald Durrell, he jumped at the chance to manage a European wildlife park in central Scotland in the late 1990s before moving on to develop two nature centers in England. He now lives with his children, Maysie and Kyle, on a 300-acre farm on the Devon/Cornwall border which he is in the process of rewilding. Derek has played a significant role in the reintroduction of the Eurasian beaver, the water vole and the white stork in England. He is currently working on a reintroduction project for the wildcat.

Ben Goldfarb is an independent journalist and the author of Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2018), which the Washington Post called “a masterpiece of a treatise on the natural world.” He is currently at work on his second book, on the ecological history of roads.