Against the Muse Myth: On Motherhood and the Writing Life

Molly Spencer Finds Time to Write in all the Smallest Spaces

When I was in my late twenties, I made a decision: a decision not to be a writer. Although I’d been writing since childhood and once had wanted to make it my profession—or, as I thought of it then and still do, my life—I was newly married and I wanted to have children. I sensed that an artistic life would be all-consuming and that motherhood would be all-consuming. I didn’t think I could do both, and I chose motherhood.

Even before the first of my three children came along, I set aside my notebooks and books on poetics and craft. Although I mourned for my writing self, for the life that might have been, I believed I’d made the best decision. Being a mother would take the place of being a writer for me, I told myself.

I was wrong, of course.

*

A few summers ago at a gathering of writers, I heard a poet speak about what he called “the trance.” He was referring, he said, to the altered state poets enter when writing. A trance, the dictionary tells us, is “a half-conscious state characterized by an absence of response to external stimuli.” It comes from the Latin trans, “across, beyond,” and ire, “to go.” Another writer at that same gathering spoke about the importance of making one’s desk a “sanctified space.” Sanctified: “set apart or declared holy.” Antonym: profane: of or related to that which is not sacred; literally “out in front of the temple”; with the moneychangers and the merchants selling doves for ritual sacrifice, sullying a holy place.

In the days and weeks that followed, both of these declarations looped in my mind and I seethed, trying to remember the last time I’d been able to avoid or ignore external stimuli, wishing I had a space set apart for my writing. I thought of waking at four-thirty in the morning when my kids were young, slipping downstairs to the kitchen to write only to have one or more of them wake soon after. I thought of all the times the oven timer or a crying child had interrupted a line of poetry coalescing in my mind, and of the phone calls I’d received from my children at the brief writing retreat I’d attended the previous year: Where is Dad? they asked when, at seven o’clock one evening, their father wasn’t home from work yet. When is dinner? I remembered my guilt when my mother asked, Are you sure you want to just go away and write? Your family needs you. I thought of all the mornings or hours or half-hours I’d planned to devote to writing that instead I devoted to fevers, trips to urgent care, dinners for unannounced visits from my in-laws, last-minute repairs to basketball uniforms, skinned knees, wounded little hearts.

Rather than wait for the trance or a sacred space, I hope writers will do their own work first.

And I thought of all the places that had been my writing “desk” over the years: mostly, the end of the kitchen table; once, a card table in my bedroom and then in a corner of the living room; then, in my late thirties, an actual desk, scuffed and handed down from my parents, pushed up to a four-foot section of wall in my kitchen, within reach of the counter on one side and the table on the other. A desk where, yes, I wrote poetry. But also a desk where often a child did homework, where often the laundry sat in baskets waiting to be folded or in stacks waiting to be put away, where most days someone’s raincoat, gym bag, hoodie, or all three were slung on the back of my chair. A desk where I paid bills and signed excuse notes and applied band-aids and wiped away tears.

I understood that these declarations—about the trance, about the desk as sacred space—had nothing to do with my life as a writer. They came from another plane of existence that I did not have access to because I am a woman, and women are still responsible for most of the housework, child-rearing, and other care-work in our society. In fact, a recent study found that caregiving fragments women’s time so much that, on any given day, a mother has on average ten minutes of uninterrupted leisure time (Schulte).

Or, as Tess Gallagher puts it in her poem, “I Stop Writing the Poem,”

No matter who lives

or who dies, I’m still a woman.

I’ll always have plenty to do.

I don’t write in a trance or a sacred space. I write in the orthodontist’s waiting room. I write in the car in the ballet studio parking lot. I write in the splinters of time I can find amid my obligations.

*

I once read an article titled “Emily Dickinson’s Handwritten Coconut Cake Recipe Hints at How Baking Figured Into Her Creative Process.” This about a woman who once wrote in a letter to a friend, “God keep me from what they call households.” I was, to put it mildly, skeptical. What actual evidence is there that baking was an important part of Dickinson’s process, other than a few lines jotted down on the back of a recipe? How did the author know that scraps of language and ideas for poems didn’t follow her everywhere—as they do most writers—and that she didn’t write them down wherever she was, on whatever she could find; that she wasn’t mid-cake when some words she’d been turning over in her head for months finally arrived as lines of a poem?

What would people think about my creative process, with my desk wedged into a small space in my kitchen? That I found the domestic sphere so inspiring I put my desk between the counter and the kitchen table?

It was a very small house. There was no other place for the desk.

At my desk, I remove a sliver from my daughter’s palm. At my desk, I plan next week’s meals. At my desk, I answer the phone because it’s school calling—my middle son is feverish, please come pick him up.

*

Having children did not, it ends up, take the place of being a writer for me. In fact, it might be that having children made forgoing the writing life impossible. Perhaps I turned back to writing after my first child was born because I felt torn awake and utterly vulnerable after pushing a defenseless human body out of my own and becoming responsible for its very life. Perhaps it was because he was born just days before the September 11th terrorist attacks so horrifically sharpened my perception of the world and our country’s place in it.

Perhaps it was because days and months and years of a child—then two, then three—needing care, needing my body, my mind, my daytimes and middle-of-the-nights, the very last shred of my energy and patience, was not enough for me. By which I mean: Although I love my children fiercely and cherish the years I spent at home with them, caregiving work was not fulfilling for me. I mean: Although I would do it all again—chanting nursery rhymes on loop, answering endless questions, wiping down the high chair a thousand-thousand times—I was unhappy.

If you have a family and have time to wait for the trance and have a physical space that you can cordon off from the rest of your life and sanctify, you are probably a man.

Amid the labor and the drudgery—and, yes, the occasional magic—of child-rearing, I felt as if the edges of my body were being erased. I missed solitude. I missed the beckoning, empty rooms of my mind. So I started writing again, waking before dawn each morning to get an hour or so of reading and writing in before the kids woke. At that time, I’d have said, “I write,” but would not have called myself a writer. Writing was a means of keeping my boundaries intact, of preserving a self amid the obliteration of motherhood.

I write in the margin of my son’s crumpled math worksheet left on the floor of the car. I write on a CVS receipt. At the produce market shopping for herbs, I write in the back of my mind.

*

The danger of the trance is the mythology behind it: that during the trance the writer is a conduit for the Muse. The concept of the Muse comes from the nine daughters of Zeus—the Muses—in Greek mythology, who guarded and apportioned human inspiration and creativity. Throughout history, the practical aspects of women’s lives, cultural norms about women’s roles, and this mythology, in which the Muse is often eroticized and ardently pursued by the artist, have made the Muse the province of men.

“Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story / of that man skilled in all ways of contending,” begins Robert Fitzgerald’s translation of The Odyssey, while Robert Fagle’s begins, “Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns.” In these lines, invocation is all: the speaker cries out, pleads for a visitation from a goddess-like muse.

Now compare Fagle’s and Fitzgerald’s language to that of Emily Wilson, the first woman to translate The Odyssey in English (and, it’s worth noting, a mother): “Tell me about a complicated man. / Muse, tell me how he wandered and was lost.” Wilson’s simple, direct commands and her plain diction are no-nonsense and conversational: Tell me. There is no crying out, no waiting, no chase, and no plea—just a sense of getting down to business. If a woman’s muse exists, it is the muse of Wilson’s translation.

I write in the bleachers at the track meet waiting for my son’s relay. I write in the car sitting in traffic. I write a line that arrives out of nowhere on the back of my hand.

*

There came a time in my life when I was very ill and couldn’t write—couldn’t grip a pen or depress the keys on my laptop keyboard, couldn’t even hold a book open because of pain and stiffness in my hands. My whole body hurt. I stopped absorbing nutrients and was anchored to a thick, leaden fatigue. I remember lying on the couch shortly after giving birth to my daughter, child number three. My mom was staying with us because I was too sick to care for the baby or her brothers, then four and two years old. I said to my mom, “I hope I can write again someday.” Her reply: “Oh, sweetheart. I just hope you’re well enough to take care of your kids someday.”

I wished that, too, but I knew that someone else would always take care of my kids if I couldn’t. And that no one else could write my poems.

In that moment I felt a little monstrous, but I also understood something for the first time. I understood what my work was: to be a writer. I understood that if I didn’t or couldn’t do this work, my life would not be my life. So perhaps what sent me fiercely and permanently back to writing was the fact of my physical suffering and the death it foreshadowed. It doesn’t matter to me now why I returned to writing. That I did is the fundamental fact of my existence.

I write on the back inside cover of the book I’m reading while my son gets a post-op ultrasound. I write while the chicken roasts.

At my desk I check the children’s grades. At my desk I sit and fold towels while my two-year-old nephew stands and folds washcloths: “Corner to corner, Aunt Molly,” he says. At my desk I sew ribbons into my daughter’s pointe shoes. I prick my finger. It draws blood.

*

In the Gallagher poem, the speaker has stopped writing the poem in order to fold laundry, and “a small girl / [is] standing next to her mother / watching to see how it’s done.” The “it” for Gallagher—whose husband died of cancer—may have been how to go on despite grief, but the “it” is also how to live as a woman lives.

Every day, I’m aware that as I pursue my writing life, as I try to juggle writing with my family’s needs and my paid work, as I persist in in trying to make something out of nothing in time and in space my life doesn’t subside for, my children are watching. I want to show them how it’s done. I want them to know that a woman is more than a caregiver. And I want to them to see that a person can do their life’s work simply by insisting upon doing it.

It’s not easy. To manage it, I live by a mantra: Do your own work first. This means a number of things to me: that I spend time every day reading and being attentive to language and (usually) writing; that I devote the best of my mind to writing and give everything else my second-best effort; that I say no to things our culture expects me to say yes to: chaperoning field trips, remembering details from school newsletters, making spaghetti for the team dinner; that I pass on invitations from friends and family; that I put boundaries around the nature and amount of paid work I do so that I have time to write; that, everywhere and every day, I preserve a province of my mind for poetry. This has sometimes caused tension in my relationships, close and not-so-close. Why? Because the culture doesn’t approve of a woman who puts her own work first: would call her selfish; would say her priorities are out of order.

I write at the sink washing dishes. I write chopping onions. I write with a baby on one hip, stirring dinner on the stove, as if my life depends on it. Because it does.

*

I’m reading an interview in which a male poet—one whose work I admire greatly, one whom I consider a friend—said that writing poems is “impossible.”

I want to spit.

Later, same day, I come across a quote attributed to Leo Tolstoy: “One ought only to write when one leaves a piece of one’s flesh in the inkpot, each time one dips one’s pen.”

Fuck that. I say it out loud. Fuck the trance, the sacred space, the “impossibility” of writing poems, the ridiculously high stakes: flesh in the ink pot.

I write in the car wash. I write in the furnace room of my parents’ basement, early on Thanksgiving morning, before it’s time to make the pies. I write in the surgery waiting room, watching the clock, waiting for the doctors to come out and say it was much more complicated than they thought it would be, but my son is going to be fine.

*

Today it hurts to write—actually hurts—because I cut my finger badly slicing bread. I take a look as see the deep red gap, flesh pulling back, and I know I should have it stitched. But I’m babysitting my feverish nephew. My son has a doctor’s appointment at three, and I have to take my daughter and three other Girl Scouts to a campground in the Santa Cruz Mountains at five. I can’t miss the window—the road in and out is one way: in from five to six only; out after six.

I write at the sink washing dishes. I write chopping onions. I write with a baby on one hip, stirring dinner on the stove, as if my life depends on it. Because it does.

So the kitchen—not the inkpot, or the page—is where I leave my flesh, just a bit on the blade of a knife. I rinse the knife and bandage my hand. I put my nephew down for a nap and walk to my desk. With my foot, I push a laundry basket away from the chair. I move the piles of bills and school forms to the side. And, waiting for nothing and no one, in the twenty minutes before the kids get home from school, I write a poem. Which is not impossible.

I write on the back inside cover of the book I’m reading while my son gets a post-op ultrasound. I write while the chicken roasts. I write one word in the next blank space of my notebook. Then I write another.

*

If we make writing into something that requires waiting for a half-conscious state to occur in a space set apart and holy, we miss out on the kind of art made in the messy, material, fragmented, actual, ten-minutes-at-a-time world where we live. We also devalue, if not exclude, from our concept of what makes a “writer,” those who don’t have time to wait for a trance, who don’t have space in their homes or their lives for writing, let alone a sanctified space.

And make no mistake, the people who get excluded have been and will be women—the caretakers of children, the elderly, and their neighbors; the ones who do the most housework at home and “housekeeping” tasks at work; the ones who are paid less for the same work as their male counterparts. And they have been and will be especially women of color, who face all of these obstacles, compounded by systemic and individual racism that creates even more roadblocks to a creative life.

I’ll be plain: If you have a family and have time to wait for the trance and have a physical space that you can cordon off from the rest of your life and sanctify, you are probably a man whose partner does most of the care-work. And there’s a good chance you’re a white man, for whom and by whom the world of creative work—and the world of all work, really—was designed.

Every day, I write whatever I can wrestle from my mind and from language, reading and listening, putting words down on the page. Often in a slender crack of time between obligations. With my simple materials: pen, paper. Despite interruptions. At my scuffed and cluttered desk that I have dragged back and forth across the country, following my husband’s jobs. Where I write poems and checks and essays and appointment reminders and book reviews and grocery lists. In a room in a house where a family lives. Apart from that which is sacred. I read and listen and write: a word, a list of words, a line, a couplet. Sometimes a whole draft, listened for, attended to, worked at, returned to. I have written lines and poems and whole manuscripts of poems; essays; criticism; and a graduate critical thesis in exactly this way. Or, as Sarah Vap puts it in Winter: Effulgences, her gorgeous and wrenching meditation on—amongst other things—interruption: my work “has sputtered out of holes, across many years, during which I was interrupted every few seconds, I. / Good morning love. Come here.”

And, yes, very occasionally, a poem—or part of a poem or most of a poem—arrives as if from a realm beyond, and I feel very nearly entranced, very nearly holy. And these times are as rare when the baby sleeps through one night after months or years of not. Are like the five minutes every six months during which there is no dirty laundry in the hamper and no one is hungry. Are like the one week every other year during which no child gets sick or hurt. But these moments are not how to write poems or books of poems. They are not how to have a writing life, especially if you are a woman or a mother.

Rather than wait for the trance or a sacred space, I hope writers will do their own work first. I hope they will labor—a word that scholars think may have derived from the Latin labere: “to totter,” in the sense of tottering under a burden—rather than wait for inspiration. I hope they will say no to whatever they have to in order to do their life’s work. I hope they will write, not in the absence of obstacles, but in the pits and gullies around and through them. Not from inspiration in the language of the Muse, but from their daily lives in the language of stovetops and bodies and brooms and blood. And interruptions.

At my desk, I cut the tags from my son’s pajamas so I can wash them and take them to the hospital during visiting hours tonight. At my desk, I check my bank account. At my desk, I sign the decree formalizing my divorce.

*

Years later, another house, the hush and brittle dark of winter before dawn. It’s six. I’m writing at my profane desk shoved into the corner of my bedroom, piled with stacks of essays I need to grade and bills that need paying, with the hum and clink of the kids eating breakfast in the background, in the midst of my actual life. My daughter taps lightly on my door, which is always ajar. She needs help with her homework.

I say, “Good morning, sweetheart. Of course I’ll help you.”

I stop writing the poem.

_______________________________________

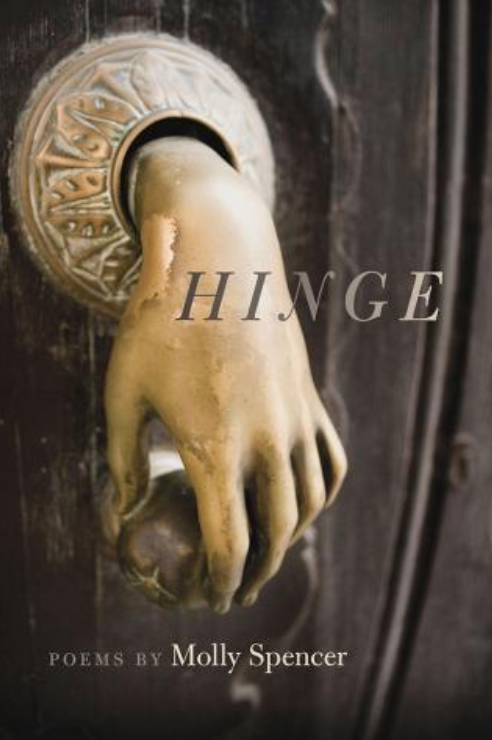

Hinge, by Molly Spencer, is out now from Southern Illinois University Press.

Molly Spencer

Molly Spencer is a poet, critic, and editor. Her debut collection, If the House (University of Wisconsin Press, 2019) won the 2019 Brittingham Prize judged by Carl Phillips. A second collection, Hinge, won the 2019 Crab Orchard Open Competition judged by Allison Joseph, and is forthcoming from SIU Press in October 2020. Molly’s recent poetry has appeared in Blackbird, Copper Nickel, FIELD, The Georgia Review, Gettysburg Review, New England Review, Ploughshares, and Prairie Schooner. Her critical writing has appeared at Colorado Review, The Georgia Review, Kenyon Review online, The Writer's Chronicle, and The Rumpus, where she is a senior poetry editor. Her poems have won a Lucile Medwick Award from the Poetry Society of America, a Glenna Luschei Award from Prairie Schooner, and a Writers@Work Fellowship Award. She holds an MFA from the Rainier Writing Workshop and an MPA from the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. Molly teaches at the University of Michigan's Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy.