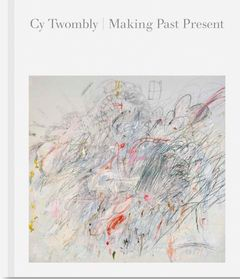

Lead image: From Six Latin Writers and Poets: Catullus, 1975–76

Graphite on paper, 25.2 x 32.8 cm (9 ⅞ x 12 ⅞ in.)

(c) Cy Twombly Foundation

Collection Cy Twombly Foundation

Photograph: Maria Enqvist, courtesy of Cy Twombly Foundation

“How to draw a line that is not stupid?” asks Roland Barthes in his incomparable essay on Cy Twombly’s handwriting. This very good question came as a comfort to me, for I’ve always disliked my own hand. Its line seems self-insistent, self-exposing, a bit bathetic—and yes, stupid. You cannot get away from yourself in your own hand. And yet Twombly does. He found his way to a hand that is no one’s, or everyone’s, or mythic, or just a stain left behind by something written there before. Barthes describes Twombly’s hand as “vague,” “gauche,” “idle,” “permitted to linger,” “drifting between desire and politeness,” and (quoting the Tao Te Ching) that of a man acting “without expectation.” No sensible person would dispute the acuity of Barthes’s observations or the golden persuasions of his style. So I will take that essay as a starting point for pondering some of the mysteries of Twombly’s hand.

Because I am no art expert, although I have studied the classics, I want to try to think about Twombly through the poems of Catullus. These two spirits seem to me somehow in tune.

Catullus, Rome, 1962

Catullus, Rome, 1962Oil paint, graphite, and wax crayon on canvas,

200 x 120 cm (78 ¾ x 47 ¼ in.)

(c) Cy Twombly Foundation

RIRA Collection, Cologne

Erudite allusion mixed with earthy expression features in the work of both. Catullus, like Twombly, was highly susceptible to the charms of the classical past, which for him meant the Greeks.

He studied and imitated the Greek lyric poets, transformed Greek meters for Latin phonetics, and translated texts of Sappho and Callimachus into fresh Roman masterpieces. But his main energy was rebellious. The staid surface of Roman poetry bored him. He broke that apart. Conventional pieties made him impatient. He defaced them. His poetic style juxtaposes crudeness on the level of graffiti (in poems of invective) with psychic autopsy as delicate as Sappho’s (in poems of love). He changed the diction of lyric verse, admitting words like lotum (“piss”) and defututa (“fucked to bits”). He changed the whole velocity of the poetic task of telling it like it is, whatever it is—he speeded up the surface. He died at thirty.

It was Twombly’s habit (so I heard from Nicola Del Roscio, Twombly’s assistant and archivist for almost fifty years) to fall in love with different poets at different times. His saison with Catullus produced the sixteen-meter-long painting Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor, begun in 1972 and finished in 1994. I don’t really know what Catullus meant to Twombly.

They had vacation spots in common, for Twombly lived part of the year in a house in the Italian town of Gaeta, where Catullus used to go on holiday in the first century bce. “Catullus had friends here. It was kind of a summer art colony, like East Hampton . . . 2,000 years ago,” Twombly told an interviewer. It amused him that Catullus’s holidays in Gaeta were spent at the home of a certain Mamurra (a Roman prefect, playboy, and favorite of Julius Caesar) to whom Catullus referred in his poems as pathicus (“fairy”) and mentula (“prick”). Gays can be hard on each other. But (again according to Del Roscio) Twombly’s deeper connection to Catullus was elegiac, as the title of the 1994 painting suggests.

Asia Minor was the ancient name for the Anatolian peninsula, modern Turkey, most of which was annexed by the Romans in the first century bce and became the Roman province of Asia. Catullus spent some time there, probably in 57/56 bce, on the staff of the Roman governor of Bithynia. Nothing is known of the events of that year, except one: his brother unexpectedly died in the Troad and Catullus went there to pay final obsequies at the grave. This was the occasion for perhaps his most well-known poem, the elegy for his brother (Poem 101):

Multās per gentēs et multa per aequora vectus

Many the peoples many the oceans I crossed —

I arrive at these poor, brother, burials

so I could give you the last gift owed to death

and talk (why?) with mute ash.

Now that Fortune tore you from me, you

oh poor (wrongly) brother (wrongly) taken from me,

now still anyway this — what a distant mood of parents

handed down as the sad gift for burials —

accept! Soaked with tears of a brother

and into forever, brother, farewell and farewell.

Twombly admired this poem particularly “because of the struggling language that covers all kinds of emotions,” Del Roscio said. The title of the painting refers, possibly quite specifically, to the poem’s last line (atque in perpetuum, frater, ave atque vale). And behind that lies the limpid surface of the poet’s grief where we can see, as in a clear dark pool, the moment when death is torn from life. It fascinates me that Barthes found evidence of this moment in Twombly’s handwriting itself, in its metaphysical impulse. Describing the gaucherie of the hand, he remarks on its lightness, its inclination to gradually erase itself and fade away. Barthes analyzes the impulse: “to link in a single state what appears and what disappears; [not] to separate the exaltation of life and the fear of death . . . [but] to produce a single affect: neither Eros nor Thanatos, but Life-Death, in a single thought, a single gesture.” Equally fascinating to see what thoughts and gestures this painting evokes from viewers. When it was shown at the Menil Collection in Houston years ago, the guard found a Frenchwoman standing in front of it totally unclothed. “The painting makes me want to run naked,” she wrote in the guest book. Twombly was delighted by her reaction. “No one can top that one,” he said to the New York Times.

Sheer velocity is what takes place on his canvas. “Everything lives in the present, it’s the only time it can live,” he said.To mingle together exposure and erasure, Eros and Thanatos, is a philosophic instinct and an artistic method that Twombly and Catullus share, it seems to me. Every method is an “act of doubt.” Twombly is not a scholar. Catullus is not his property. But “Catullus” gives him a spurt of joy to write. Illegibility, unloveliness, misspelling are all ways to disavow ownership or power over its meaning, while retaining an ancient presence that glows up through the work. We should note in passing that the proper title of the 1994 painting is Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor). Parentheses suggest Twombly’s hesitation to lay claim to Catullus directly.

130. Primavera, from Quattro Stagioni, Bassano in Teverina and Gaeta, 1993–94. Synthetic polymer paint, oil, house paint, pencil and crayon on canvas. 10′ 3 1/8″ x 6′ 2 7/8″ (312.5 x 190 cm). Gift of the artist. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, U.S.A. Photo Credit: Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

130. Primavera, from Quattro Stagioni, Bassano in Teverina and Gaeta, 1993–94. Synthetic polymer paint, oil, house paint, pencil and crayon on canvas. 10′ 3 1/8″ x 6′ 2 7/8″ (312.5 x 190 cm). Gift of the artist. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, U.S.A. Photo Credit: Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Indirectness, people say, was characteristic of Twombly’s conversational manner too. He would stop and start, become inaudible, trail off, cover his mouth with his hand. Yet sheer velocity is what takes place on his canvas. “Everything lives in the present, it’s the only time it can live,” he said. What Catullus brought to Roman poetry was this very zing of a moment in time. That is the genius of a lyric poem—to cut out and frame for you a microblast of “now.” And no one celebrates its ephemerality more jubilantly than Catullus, except perhaps Twombly. Everything lyric happens only once, the world, your heart. Consider the poem Catullus wrote when he left Asia Minor—partly an ode of departure and partly a tribute to the season of spring—alongside Twombly’s utterly joyous canvas Primavera (Spring), from Quattro Stagioni (The Four Seasons). My Catullus translation here is somewhat free because this poem in Latin has in it all the release and exuberance of a young man stirring to a journey—it has light and leaves and sun-whipped waves; it has clear new breezes, ancient deserts, and a raw green longing to be gone; it has trembling for the future and a hint of sadness for the past, the sweetness of comrades and the strut of a poet addressing himself (Poem 46):

Iam vēr ēgelidōs refert tepōrēs

Now spring unlocks!

Now the equinox stops its blue rages quiet

as pages.

I tell you, Catullus, leave Troy, leave the ground burning, they did.

Look we will change everything, all the meanings,

all the clear cities of Asia you and me.

Now the mind, isn’t she an avid previous hobo?

Now the feet grow leaves so glad to see whose green baits awaits.

Oh sweet don’t go

back the same way, go a new way.

And there goes Catullus setting off for the future in primavera brushstrokes. “Ancient things are new things,” Twombly said.

__________________________________

From Cy Twombly: Making Past Present. Used with the permission of MFA Publications.