After Reconstruction, Black Women Found Opportunity for Revolt in Church

And White Suffragists Often Stood in the Way

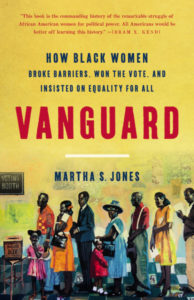

The following was excerpted from Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All by Martha S. Jones, which has been shortlisted for the 2021 Cundill History Prize.

*

When Black women spoke about power, they used a term that was as vague as it was blunt. They found it sometimes necessary to be that forceful, especially in contests with men who spoke in metaphors of war. Yes, battles ensued when Black women aimed to exert authority over men—in churches, at conventions, and at the ballot box. But that did not form the whole picture.

Anna Julia Cooper offered a more nuanced portrait of what power looked like. It included self-governance: “Only the Black woman can say when and where I enter.” It was driven by a quest for dignity: “The quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood.” Her power would not come at the expense of others or by gamesmanship: “Without violence and without suing or special patronage.” And her ultimate aim was dignity for men and women both. Cooper explained that when she as a Black woman took her seat or cast her ballot, “the whole Negro race enter[s] with me.” Women’s power was a route to dignity for all.

Reconstruction offered an unprecedented set of promises to Black Americans. Southern states, as a condition of reentry into the Union, rewrote constitutions that fulfilled the purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment. Black Americans wasted no time and clamored to enter politics, at conventions, in legislative chambers, and in the streets. For the first time, Black Southerners acted as agents of their own governance—making laws and setting the terms for how power and resources would be shared.

With the more than 2,000 African Americans who held office during Reconstruction—from a US senator and Congress members to sheriffs and postmasters—the reality of a nation that was beyond slavery and white supremacy came into view. By the presidential contest of 1868, Black men in the North and South were at the polls, many of them casting their very first votes.

Black women also played a part in this radically new scene. Black men may have been positioned to cast ballots, but women shaped all the deliberations that led up to Election Day. Black-led political meetings included women who helped to steer the future of their communities. Women’s presence and their voices ensured that this new political culture was porous, informal, and alive with community spirit.

Men would eventually serve as delegates, chairs, and spokespeople, but women prepared them to reflect the views of their families and their communities. When Election Day came, women went the polls and kept watch for those who might try to intimidate men who came out to cast their ballots.

There was no reason to think that any constitution would protect Black women.

Black women knew the power of the vote and what it meant to use it. How to get there was the question. One way forward might have been joining the work of two new national women’s suffrage associations: the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), where women were lobbyists and organizers and spearheaded litigation. But only a small number of Black women joined these new suffrage associations.

The racism that persisted there often drove them out. And suffrage alone was too narrow a goal for Black women. They went on to seek the vote, but on their own terms and to reach cures for what ailed all humanity. The vision that Harper had promoted in the American Equal Rights Association showed Black women their own path.

Too soon, Black women learned that the urgent interest of all of humanity included those very close to home: that of their husbands, sons, and fathers. The hard-won voting rights of Black men were under attack. Starting in 1877, federal authorities—Congress and the courts—made a devastating pullback from enforcement of Reconstruction’s democratic promise. State by state, Southern lawmakers began to roll back the gains that new constitutions and civil rights acts had promised. This regime change took hold over the course of two decades, imposed by fits and starts, but from the start it was part of one movement that aimed to reimpose white supremacy.

Violence and intimidation worked together with poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and literacy tests to keep Black men from the polls and office holding. The United States was on its way to a new political order, a new American apartheid regime built upon disfranchisement, segregation, and lynching, known colloquially as Jim Crow.

There was no reason to think that any constitution would protect Black women. Their rights were tested early on right where Frances Ellen Watkins Harper had told the AERA that they mattered most, in transportation. In 1872, Josephine DeCuir tested who she was before the law after a steamboat company refused her entry into a ladies’ stateroom as she headed north, up the Mississippi from New Orleans. In protest, DeCuir spent the night in an anteroom intended for nursemaids and their charges rather than lay her head in the “bureau,” short for the Freedmen’s Bureau, the colloquial moniker that Southern ship operators gave to their quarters for Black passengers.

DeCuir was not a newcomer to this dilemma. Captains and clerks later recounted the many instances in which she had groused, held fast to a white-only ladies’ seat, and insisted on equal access. She spoke only through her lawyer during the lawsuit—in a complaint, during cross examination, through briefs—never submitting to questioning. That would only repeat the original offense.

DeCuir relied upon Louisiana’s 1868 Constitution, a text drafted by radical men, Black and white. Article XIII guaranteed: “All persons shall enjoy equal rights and privileges upon any conveyance of a public character… without distinction or discrimination on account of race or color.” In the proceedings, DeCuir heard the steamboat’s indignities now recrafted into words. She was curiously said to be like a white man—someone absolutely barred from the ladies’ cabin. She was also compared to “repulsive and disagreeable” persons whom everyone agreed steamboat operators could exclude, segregate, and expulse at will.

At the US Supreme Court, the state laws that guaranteed DeCuir’s right to travel as she chose were said to violate the US Constitution’s commerce clause, an impermissible regulation of trade between the states. It was a clinical conclusion that could not cool the hot indignity that DeCuir felt.

The doors to courthouses and legislatures were closing on Black women who aspired to win their rights and preserve their dignity. There was, however, another opening. In their churches, Black women saw the chance to make a revolution that was all their own. There, debates over women’s power had a long history and struggles in churches kept Black women close to the institution-building work in which they took pride. A churchwomen’s movement kept them linked to men, children, and even those women who opted out of politics. Churches also insulated Black women from the worst that white supremacy had in store.

Amanda Berry Smith had success in the pulpit but never managed to breach the color line that divided her from white women preachers.

The early years of Reconstruction kept preaching women busy as their churches shifted their focus from the North to the South. The AME Church relocated its headquarters from Philadelphia to Tennessee, and the AME Zion Church similarly left New York for North Carolina. Church leaders—especially those among Black Methodists—called upon women to help fill new sanctuaries with new converts. The status of these women was, however, far from settled.

Women worked in their churches holding only loose and even unorthodox understandings of how high they could rise. Even as they faced uncertainty and skepticism, these women widened their circles, preached across lines of denominations and of color. They relied on a time-tested strategy: women’s effectiveness would win them expanded power.

Amanda Berry Smith had success in the pulpit but never managed to breach the color line that divided her from white women preachers. She had been born enslaved just outside of Baltimore. Her father worked to liberate their family and relocated Smith and her siblings to the Free State of Pennsylvania. Her parents saw to it that Smith went to school, but too soon she was sent out to work, earning her living as a domestic worker, a cook, and a washerwoman.

Her hardships only increased when Smith lost first one and then a second husband, along with four of her five children. She had long sensed that she was called to preach, but widowhood gave Smith the freedom to learn precisely what that meant. Smith got her start at her local sanctuary, Philadelphia’s Green Street AME Church. By 1869, she was traveling regularly between churches and camp meetings, where she became known as a powerful evangelist, a reputation that eventually carried Smith and her ministry to England, India, and Africa.

Smith never felt limited by the obstacles that men placed in her way. Many Christian leaders drew sharp lines between denominations. Smith did not. She paid little mind to whether her hosts were Methodists, Baptists, or Presbyterians. She preached to anyone who would listen. Though born in Maryland, Smith never regarded herself as limited by her Southern roots or her origins in the United States. She traveled the world and found common ground with other Christians and candidates for conversion everywhere she went.

Smith also did not defer to any color line. Her greatest supporters were laywomen—Black and white. Smith knew how some church leaders used women’s sex to limit their power. She pushed back, speaking out openly in support of women’s right to preach and be ordained to the ministry.

The racism Smith encountered marred her work. Often, white women preachers kept her at the margins. She was disappointed in more than one encounter with Sarah Smiley, a popular preacher who started life as a Quaker but spent her career preaching to a wide range of Christian sects. In 1870, Smith was invited to hear Smiley speak during a Bible reading at the Twenty-Fourth Street Methodist Church in Brooklyn, New York. Upon arrival, Smith was encouraged to sing a hymn prior to Smiley’s taking the pulpit, and she obliged.

Smith then stayed on to hear Smiley’s Bible reading but was taken by surprise when she was inexplicably escorted out of the sanctuary. One of Smiley’s confidantes explained that Smith was not welcome to share the venue with her white counterpart. Smith left, tearful and despondent.

Smith and Smiley met a second time in another awkward encounter when both were touring Britain. Smiley offered Smith advice about her preaching schedule and, at first, her suggestion sounded generous. Smiley discouraged Smith from making a stop at Broadlands, where, Smiley advised, Smith would encounter ideas that would trouble her mind. Smith kept to her original schedule and only later discovered Smiley’s true, self-serving intention.

Smiley hoped to redirect Smith to where Smiley’s associates hoped that Smith would draw large crowds to their events. Smiley did not mean to protect Smith from troubling ideas; she had meant to save her own supporters from the disappointment and embarrassment of small crowds. Smith only learned this later, a discovery that left her feeling exploited by another preaching woman.

Smith was also slighted in print. She never met Phebe Hanaford, author of the 1877 book Women of the Century, published for the centennial of the United States to document the national debt owed to women. Hanaford was an ordained pastor in the Universalist Church, a suffragist allied with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan Anthony and the American Equal Rights Association, and a prolific writer. Her 640-page tribute to American women included hundreds of biographical essays that highlighted women’s “patriotism, intelligence, usefulness, and moral worth.” Across 27 chapters, Hanaford charted women’s contributions to US history and culture. Somehow, she overlooked Amanda Berry Smith.

Hanaford did mark the achievements of African American women, though only in a paternalistic and diminishing tone. She wrote of women like the 18th-century enslaved poet Phillis Wheatley, who demonstrated Black women’s intellectual capacities: “Even African women, despised as they have been, have intellectual endowments.” The part that Wheatley’s “mistress” played in the poet’s education further demonstrated the virtue of white slaveholding women: “Colonial women, though some of them slaveholders, were not destitute of a lively interest in those the custom of the times placed wholly in their charge.”

Preaching women, Black and white, agreed that men regrettably monopolized the pulpit, leaving women unacknowledged and uncompensated for their talents and labors.

Mary Peake, a teacher of former slaves on the Sea Islands, evidenced the morality of the American Tract Society when it endorsed “Christian effort without regard to race or color.” Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was “one of the colored women of whom white women may be proud.” Why other women should take credit for the self-made Harper, Hanaford never explained.

Among those noted under the heading “Women Lawyers,” was Charlotte Ray, an 1872 graduate of Howard University Law School: “Ray… said to be a dusky mulatto, possess quite an intelligent countenance.” She “doubtless has also a fine mind, and deserves success.” Sculptor Edmonia Lewis was included among “Women Artists,” a “waif” possessed of “perseverance, industry, genius, and naïveté,” all of which had earned her the admiration of white Americans. In every instance, Hanford offered only backhanded praise when it came to Black women.

Hanaford gave generous space to churchwomen activists of all sorts. Three chapters—“XIII. Women Preachers,” “XIV. Women Missionaries,” and “XIX. Women of Faith”—made up 15 percent of the book overall. Hanaford lauded the great contributions that American women had made to religious life. The same chapters were, however, remarkable for whom they left out. Not one African American woman nor one Black churchwomen’s organization is mentioned. It is a notable omission.

Hanaford certainly was aware of Smith and women like her. The Woman’s Journal, one of Hanaford’s principal sources, along with the national press reported regularly on Smith’s work. It was an awkward oversight and at worst it was an erasure of Smith and other Black women preachers.

Critics subjected all preaching women to similar criticism. In turn, preaching women, Black and white, agreed that men regrettably monopolized the pulpit, leaving women unacknowledged and uncompensated for their talents and labors. All women faced skepticism when they stepped into the pulpit, and they defended themselves by claiming a true calling from God.

Laywomen supported preaching women—as hosts during their visits, companions during their travels, and devoted listeners during their sermons. Still, a color line kept Smith from Smiley’s meeting halls and Hanaford’s pages. Not to be overlooked or forgotten, Smith wrote herself into the record in 1893 when she published her life story, An Autobiography: The Story of the Lord’s Dealings with Mrs. Amanda Smith, the Colored Evangelist.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All by Martha S. Jones. Copyright © 2020. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Photo courtesy the Tennessee Visual Archive, from a 1915 issue of The Crisis, devoted to women’s suffrage.

Martha S. Jones

Martha S. Jones is the Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor and professor of history at Johns Hopkins University. She is president of the Berkshire Conference of Women Historians, the oldest and largest association of women historians in the United States, and she sits on the executive board of the Organization of American Historians. Author of Birthright Citizens and All Bound up Together, she has written for The Washington Post, The Atlantic, USA Today, and more. She lives in Baltimore, MD.