Advice from Montaigne: You Want to Be Wise? Don't Read Too Much.

The Father of the Modern Essay Was Really Quite Unpretentious

In any debate over education, someone invariably mentions Rabelais and Montaigne: Rabelais, who argued via his creations Gargantua and Pantagruel that a school should be an “abyss of knowledge,” and Montaigne, who preferred a man with a “well-made head” rather than a “well-filled” one. These two concepts, laid out here in opposition to one another, are the two objectives of every pedagogical endeavor: knowledge on one hand, and skills on the other, to use modern jargon. Montaigne protested against overstuffing pupils’ heads in the chapters “Of Pedantry” and “Of the Education of Children” in Book One of the Essays:

“In plain truth, the cares and expense our parents are at in our education, point at nothing, but to furnish our heads with knowledge; but not a word of judgment and virtue. Cry out, of one that passes by, to the people: ‘O, what a learned man!’ and of another, ‘O, what a good man!’—they will not fail to turn their eyes, and address their respect to the former. There should then be a third crier, ‘O, the blockheads!’ Men are apt presently to inquire, does such a one understand Greek or Latin? Is he a poet? or does he write in prose? But whether he be grown better or more discreet, which are qualities of principal concern, these are never thought of.”

Montaigne is putting the teaching practices of his time on trial. The Renaissance claimed to have broken with the darkness of the Middle Ages and rediscovered ancient learning, but quantity of instruction continued to be favored over the quality of its assimilation. Montaigne preferred wisdom to knowledge for its own sake, denouncing the folly of an encyclopedic education in which learning became a goal in itself. Knowledge, he believed, matters less than what one does with it; that is, practical know-how and life skills. People may admire wise men, but they respect knowledgeable men. Montaigne goes on to drive his point home:

“We should rather examine, who is better learned, than who is more learned. We only labor to stuff the memory, and leave the conscience and the understanding unfurnished and void. Like birds who fly abroad to forage for grain, and bring it home in the beak, without tasting it themselves, to feed their young; so our pedants go picking knowledge here and there, out of books, and hold it at the tongue’s end, only to spit it out and distribute it abroad.”

I will return to Montaigne’s suspicion of memory. He often apologizes for lacking a good memory, but deep down he does not mind at all, for memory is not an asset when it is used at the expense of judgment. Montaigne compares reading, and any kind of instruction, to digestion. Lessons, like food, should not only be tasted with the lips and swallowed raw, but chewed slowly, and ruminated on in the stomach, in order to nourish the body and mind with their content. Otherwise we vomit them back up, like foreign food. Education, according to Montaigne, is about acquiring knowledge; children must make this knowledge their own and integrate it into their own judgment.

The debate over the purpose of schooling has yet to be resolved. To sum up the positions, though, it would be unfair to pit Montaigne’s liberalism too hastily against the encyclopedism of Rabelais. First of all, though the letter from Pantagruel to Gargantua may seem to propose exhaustive, excessive learning, we must remember that it is intended for a giant. And the letter goes on to give a piece of advice that Montaigne would not have disagreed with: “Knowledge without Conscience is but the ruin of the soul.” Conscience—that is, honesty and morality—is indeed the end goal of all teaching. It is what remains when digestion is complete and we have forgotten almost everything else.

*

Montaigne was distrustful of education that was too scholarly, as I have just discussed. In alignment with the great polarity that marks the thinking in the Essays, the opposition of nature and art, of good nature and evil artifice, erudition is more likely to distance us from our own true nature than to put us closer in touch with it. Montaigne tells us with pride that his readings have not turned him away from his own nature, but, on the contrary, have enabled him to understand it.

“My manners are natural, I have not called in the assistance of any discipline to erect them; but, weak as they are, when it came into my head to lay them open to the world’s view, and that to expose them to the light in a little more decent garb I went to adorn them with reasons and examples, it was a wonder to myself accidentally to find them conformable to so many philosophical discourses and examples. I never knew what regimen my life was of till it was near worn out and spent; a new figure—an unpremeditated and accidental philosopher.”

This definition, found in “Apology for Raimond Sebond,” is a superb description of Montaigne’s personal ethics, at once modest and ambitious. Montaigne is telling us two essential things. The first of these is that he has made himself who he is, that his readings and the knowledge he has acquired have neither changed him nor degraded him; that his manners—that is, his character, his behaviour, his moral qualities—are his own, and not modelled on anyone else’s. The second thing Montaigne’s words tell us is that, when a person writes, and speaks, and talks about himself with examples and explanations—that is, giving specific cases and his reasoning in these cases—that person will begin to see himself in books.

Montaigne is telling us that writing and describing himself enabled him to understand not only who he was, but the system or group or school of thought with which he identified the most. In short, Montaigne did not choose to become a Stoic, or a skeptic, or an epicurean—the three philosophies with which he is most often associated—but he has recognized now, late in life, that his behavior conformed naturally to one or another of these doctrines, by chance, and spontaneously, without planning or deliberation.

Montaigne often apologizes for lacking a good memory, but deep down he does not mind at all, for memory is not an asset when it is used at the expense of judgment.

This is why it would be wrong to explain Montaigne in terms of his belonging to this or that Classical-era philosophical school. Montaigne detests authority. If he aligns himself with an author, it is to indicate an accidental discovery, and if he refrains from mentioning the name of an author he cites, it is so that his readers will learn to be wary of any claims of authority, as he says in the chapter “Of Books”:

“I do not number my borrowings, I weigh them; and had I designed to raise their value by number, I had made them twice as many; they are all, or within a very few, so famed and ancient authors, that they seem, methinks, themselves sufficiently to tell who they are, without giving me the trouble. In reasons, comparisons, and arguments, if I transplant any into my own soil, and confound them amongst my own, I purposely conceal the author. [ . . . ] I will have them give Plutarch a fillip on my nose, and rail against Seneca when they think they rail at me.”

If Montaigne conceals the sources of some of his ideas, it is so that his readers will not be swayed by the prestige of the ancients, and so that they will feel able to challenge their authority, just as they might challenge Montaigne’s own.

*

In the chapter “Of Three Commerces” in Book Three, Montaigne compares the three types of companionship that have occupied him for most of his life: that of “beautiful and honorable women,” of “rare and exquisite friendships,” and finally, of books, which he deems more profitable and healthful than either of the first two attachments:

“These two engagements are fortuitous, and depending upon others; the one is troublesome by its rarity, the other withers with age, so that they could never have been sufficient for the business of my life. That of books, which is the third, is much more certain, and much more our own. It yields all other advantages to the two first, but has the constancy and facility of its service for its own share.”

Montaigne has not had another real friend since La Boétie’s death, and in the chapter “Upon Some Verses of Virgil” he laments the decline of his sex drive. These two kinds of contact undoubtedly give rise to more feverish displays of feeling, more intense sensations, because they involve interaction with other people—but they are also more fleeting and unpredictable, and more prone to interruption. Reading, however, offers the twin advantages of patience and permanence.

This parallel between love, friendship, and reading, which compose a sort of gradation, might seem shocking. We might think Montaigne is telling us that reading, which requires solitude, is superior to any relationship involving another person, which are merely diversions that take us away from ourselves. Books, then, would make better friends or lovers than real people. But before we jump to this conclusion, we should remember that Montaigne never sees life as anything but a dialectic between the self and others. Though the rarity of friendship and the fleeting nature of love may drive us to favor the refuge of books, reading will inevitably lead us toward other people. Still, of the “three commerces,” we must admit that reading is the best:

“It goes side by side with me in my whole course, and everywhere is assisting me: it comforts me in old age and solitude; it eases me of a troublesome weight of idleness, and delivers me at all hours from company that I dislike: it blunts the point of griefs, if they are not extreme, and have not got an entire possession of my soul. To divert myself from a troublesome fancy, ‘tis but to run to my books; they presently fix me to them and drive the other out of my thoughts, and do not mutiny at seeing that I have only recourse to them for want of other more real, natural, and lively commodities; they always receive me with the same kindness.”

The companionship of books is always available. Old age, loneliness, idleness, boredom, grief, anxiety—all of these hardships we encounter in the ordinary course of life can be alleviated by reading, if our distress is not too acute. Books soothe our worries, offering aid and assistance.

Yet there is a hint of irony in this attractive portrayal of books. They never complain, or protest when they are neglected, as flesh-and-blood men and women do. The presence of books is always a kindly and serene one, while the moods of friends and lovers vary.

Poised on the brink of the modern era, Montaigne was one of those who, through his praise of reading, helped to introduce the culture of printed material. At a time when we may be on the verge of leaving it behind, it is good to remember that men and women found comfort, understanding, and familiarity in books for centuries in the western world.

__________________________________

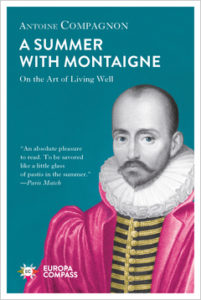

From A Summer With Montaigne by Antoine Compagnon, translated from the French by Tina Kover. Used with permission of Europa Editions. Translation copyright © 2019 by Europa Editions.

Antoine Compagnon

Antoine Compagnon is a Professor of French Literature at Collège de France, Paris, and the Blanche W. Knopf Professor of French and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, New York. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and holds honorary degrees from King’s College London, HEC Paris, and the University of Liege.