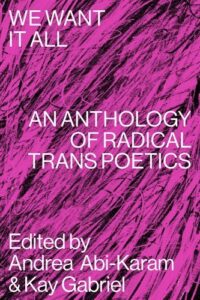

For this installment in a series of interviews with contemporary poets, contributing editor Peter Mishler corresponded with Andrea Abi-Karam and Kay Gabriel, editors of We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics. Selections from this anthology as well as the anthology’s introduction (via Nightboat Books) were featured at Literary Hub in 2020. Conducted by email, this interview’s questions and answers were later arranged for continuity.

*

Peter Mishler: Is there a phenomenon or experience, event or occurrence after the anthology was published that now with some distance you wish you could have included or that may have complicated or augmented what is already here?

Andrea Abi-Karam and Kay Gabriel: One thing that comes to mind here is that we began writing the introduction as the COVID pandemic took off in March 2020; we edited the document we had written after the George Floyd rebellion in May-June.

We didn’t predict these events of intensifying crisis and clarifying political response, any more than we could have predicted other moments of significance for class struggle on an international scale—the electoral victories of the socialists Luis Arce in Bolivia and Pedro Castillo in Peru, for instance, or the mass farmers’ strike in India—and conditions will continue to change and develop in forms whose general shape we can only guess at.

That’s a long way of saying that we can’t aim at completion in our attempt to account for and address the conjuncture, but we can help prime people to be better readers of their own situations and at the currents, patterns and forms of struggle and consciousness developing around them.

Poetry isn’t an art made by singular geniuses, it partakes in a series of social and collective practices of making meaning and languageSo, for instance: we didn’t predict the wave of anti-trans legislation that took off at the start of 2021 in the US, although the moral panics around young trans people have been developing for a while. These panics typically attempt to enlarge fears about the sexual content of gender transition, and one response from elements in the trans community has been to defensively insist on our own sexual conservatism—think about the no kink at pride discourse, for example.

We Want It All takes the totally opposite approach. We embrace, and try to get our readers to understand, that if being trans in some sense always bears on sexuality and has a relationship to how we want to be desired and fucked, that’s something we need to insist on, it’s a dimension of trans experience with a real political character, and making compromises for our safety by insisting that trans people as the politically appropriate subjects of state rights aren’t really sexual freaks is only going to intensify forms of legislative repression of queer and trans people. So, again, we didn’t predict the event, but our hope is that we’re contributing towards how people respond to it.

PM: Could you talk about what you see as one of the most intentional or most important editorial decisions you had to make, small or large? I was struck by the alphabetizing as well as the anti-colonial and indigeneity-affirming acknowledgments about the site of editing and publication.

AA-K and KG: Sure thing. As you point out, we include a land acknowledgement—we compiled We Want It All on unceded Lenape, Canarsie, Munsee and Shinnecock land. We also sequenced the contributions alphabetically by first name, and we did so specifically in order to let our contributors lead with their own—typically self-chosen—names rather than a family name. We also took a really maximalist approach to the acknowledgements, which felt like an appropriate departure from the practice that feels more common in poetry of naming a select handful of friends in the acknowledgements section. The book comes out of a series of political and cultural contexts, and we tried to find a place within it to name some of those.

One thing we’re witnessing is that trans writers are attempting to produce and reproduce aesthetic registers that can map crisis, stake an opposition, and provide the ceaselessly creative grounds for response, thought and collectivityOne less-visible editorial decision that we made was to offer edits to a sizeable handful of our writers, who had sent us strong contributions that we felt would be more effective with small but significant edits. This is relatively uncommon for poetry submissions—although there’s no reason that has to be the case: poetry isn’t an art made by singular geniuses, it partakes in a series of social and collective practices of making meaning and language, so an editor can in theory offer suggestions and corrections in a similar way to the editing and publishing of prose. In any case, our contributors were really receptive: sometimes they accepted the edits, sometimes they pushed back and demonstrated that we had misunderstood the necessity or importance of their original phrasing. And that made for a stronger volume overall.

PM: Looking at the work of all these poets together, have you noticed any literary gestures or techniques in the anthology that you see as something that radical trans poetics shares that you wouldn’t have expected? Or are there other patterns that have emerged or particular dissonances that you find fascinating as the poems converse with each other across the anthology?

KG: Well, I’ll offer a gentle speculation here that I think there are a handful of different intellectual and writerly strands that we need to follow that can help situate the current explosion of both formally inventive and ideologically anti-capitalist writing by trans poets right now.

One is the reprinting of some really signature poetic works of the Black radical tradition, like the SOS compilation of Amiri Baraka’s work, the recently released Wicked Enchantment: Selected Poems from Wanda Coleman, or Henry Dumas’s Knees of a Natural Man: these are really capacious works, formally and politically, whose reentry into circulation I think helped to spark a number of different recent and ambitious poetic engagements really across lines of race and gender.

Similarly, Gwendolyn Brooks’s Riot has been circulating widely in PDF form, and I think the different registers that Brooks delves into in that poem—rich, explosive satire; intimate, lyrical portrait; effusive and fast-paced argument: “However, what / is going on / is going on”—are enormously instructive for poets right now, trans poets included, who want to right what might be called a movement poetry that isn’t limited to the standard or canonical registers of movement poetry.

The epistolary in particular we think is generative for trans poets because it allows for an intimacy without disclosureAnother is the rediscovery and reprinting of gay and trans writing from previous decades that previously had only circulated in snippets, and here I’m thinking of the selected Lou Sullivan diaries as well as things like Larry Mitchell’s Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions, Mario Mieli’s Towards a Gay Communism—both of which flow pretty fluidly between making arguments based on sexuality and making arguments based on gender—and maybe some of the work of Viviane Namaste and kari edwards. Trish Salah is another writer I think about here: her first collection, Wanting in Arabic, is back in print as of 2014, and Metonymy Press re-released her book Lyric Sexology, Vol. 1.

Trish is a contributor to We Want It All as well, and her writing and theorizing has had I think a really significant impact on a lot of trans poets on the political left whose writing takes an experimental bent. All of this adds to the really vivid work underway right now in trans studies, and I think a lot of trans poets are pretty nerdily tuned into that work. And then some of the rediscovered or reprinted work is colliding with particular force into the relatively new formation of trans Marxism, which Jules Gleeson’s and Elle O’Rourke’s Transgender Marxism (Pluto Press, 2021) collects. There’s at least one overlapping author between Jules and Elle’s collection and ours—Nat Raha, who demonstrates the generative force of this line of thinking.

I also think that relatively young trans writers, largely but not only in the US and Canada, are encountering both New Narrative and Language Poetry in a serious way; a lot of this work which was previously out of print is, again, back in print, accessible at low cost and therefore circulating around and inflaming people’s imagination about what’s possible to write.

Because we missed the generation in which New Narrative and Language Poetry were placed in opposition to each other, we really don’t encounter or experience them that way, or at least that opposition is more abstract and people feel freer to do what they want. That means that writers can turn to both canons for techniques that feel permissive and licentious, and trans writers are often looking for permission and license. So if New Narrative elevates gossipy, pornographic writing into literary material, trans writers get a kick out of that, and if Language Poetry urges, in Bernadette Mayer’s words, to “work your ass off to change the language,” trans writers get a kick out of that.

But finally I think any discussion of the anti-capitalist bent of writers at present, and how they attempt to respond to those feelings with both aesthetic and political radicalism, doesn’t just come down to aesthetic influences. It has a lot to do with the fact that trans people, like most people right now, live in relatively precarious ways, in a conjuncture defined by crisis on multiple fronts—ecological, economic, epidemiological.

So one thing we’re witnessing is that trans writers are attempting to produce and reproduce aesthetic registers that can map crisis, stake an opposition, and provide the ceaselessly creative grounds for response, thought and collectivity. That means that even though patterns are emerging in our radicalism, the specific shapes are continually changing to match shifting conditions and to shape consciousness in certain directions, as they should be.

We responded to what we believe is an emergent structure—formally inventive, anti-capitalist writing by trans poets, whose experiments have something to do with political radicalism—and we used the anthology as a way to guide attention towards itPM: Would you be willing to walk me through a little bit of what it looked like to work together on this? I imagine that at some point there was some special synchronicity or coincidence as there is with any act of art making, where something just made sense in ways that defied a logical explanation?

AA-K and KG: We read the submissions first individually and then we read them again together, and we talked through every single one: what we thought it was trying to accomplish, what its methods were, what we found compelling in its language, imagery, or form, did it actually follow through on its promises. The submissions ended up really falling into certain patterns we hadn’t predicted but felt gratified to see—like we say in the introduction, the sizeable number of epistolary poems, serial poems and poems that substantially rewrite other cultural documents.

At the time—this was fall 2019—we would meet up every week and go over 20-30 submissions and then head out to a bar or a party together. Assembling and proofing the collection took an enormous amount of work, but we tried to inject a lot of our own vivacity and joy into the process.

PM: What conjectures can you make about the serial, epistolary, or cultural rewriting, and why you think those forms are of interest, workable, or viable for trans poets?

AA-K and KG: There’s a certain resilience that we see across these forms, especially in seriality. We talk about Harry Josephine Giles’s “Abolish the Police” series a lot, and it’s worth noting that Josie only sent us ten of their poems with that title—they have at least 90 more.

Seriality, epistolary poetry and rewriting or recomposition are all forms that require a certain kind of duration: epistolary requires a commitment to a correspondence, so to speak; cultural rewriting necessitates the incorporation of multiple layers of reading and reception at different points of time; seriality implies that part of the project of writing is that a series could keep on going forever, like Fibonacci numbers marching into an ellipsis. So part of reading these forms requires a commitment to their duration—which is what you could call a formalization of resilience.

The epistolary in particular we think is generative for trans poets because it allows for an intimacy without disclosure, and in that sense it’s tempting to trans poets who love to write about themselves, indulgently, without being forced to tell on themselves.

Cultural rewriting appeals for trans writers who, in Trish’s words, are frequently taken as “the objects, not subjects, of discourse”; in a pretty straightforward sense, rewriting inverts that relationship, in addition to appealing to a generally camp sensibility. And in general these registers are really conversational and discursive: they arise out of daily speech, which makes sense for people who live, often, high-intensity, high-contact lives. We’re not monks in our cells, and we don’t write like it.

PM: After experiencing this book in finished form, I am curious about what effect, meaning, resonances, or syntheses you think have ultimately occurred because of your unique decision to include carefully interspersed writings by those “who’ve passed alongside contemporary trans writing.”

AA-K and KG: To start with, one of the commonplaces about both political radicalism and poetry that we’re disputing is the idea that these practices and forms of thinking and writing belong to the young. This is a false and often dangerous impression: it encourages us to ignore both writers and organizers with real depth of experience, and the creativity that can develop out of that experience, and urges a superficial attachment to youth. Actually, that’s something that Bryn Kelly’s essay on Adrienne Rich talks about explicitly, and Bryn herself is one of the deceased writers whose work we sought out for the anthology.

Against the bourgeois media narrative that portrays the current wave of trans identity and cultural production as emerging almost from nowhere, we wanted to emphasize that trans radicalism, including trans cultural production, has a history, and we become better writers, thinkers, and movement workers the more we’re able to engage with this history and the less we imagine our own contribution to be the first or only of its kind.

And we think that people really responded to this inclusion! We want to highlight Bryn’s essay—“Diving Into the Wreck,” titled as both a nod to and dig at Rich—in part because she’s probably the writer we included who has received the least institutional recognition following her death in 2016. Anecdotally, people have really read and engaged with that contribution. Similarly with the excerpt from Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues: in the afterword essay for Jules Gleeson’s and Elle O’Rourke’s Transgender Marxism, which Pluto Press released this spring, Jordy Rosenberg constructs a really generous interpretation of the whole anthology around our decision to include the letter that opens Feinberg’s novel.

PM: Have you noticed any particular developments in either of your own work as artists that you feel has come from taking on this editorial role?

KG: Honestly, one of the effects of reading many other people’s writing with a lot of closeness and attention is that I’ve become a much more patient reader, and much more willing to be energized to write by other people’s work. Like, there were some submissions I’d read that made me rush maniacally to write something also, as if I couldn’t wait to be in some kind of disjointed correspondence with this type of project. That’s coming across in a current project, a long poem synthesized out of my dream journals and the recorded dreams of my friends, much of which uses their own language and syntax pretty closely.

AA-K: The process of working on We Want It All has certainly pushed me into new bounds with regards to craft. In line with the abundance of epistolary and New Narrative-minded work we received, I’ve been hard at work on my poet’s novel, a lengthy piece of prose with more distinctly executed narrative structures than the hyper-polyvocality I typically work with in poetry. The breadth and unruliness of all of the various forms in We Want It All on some level gave me permission, or let me give myself the permission to dive into a genre that I’m not formally trained in, whereas in poetry I have the MFA under my belt as an institutional foundation. The anthology is an ongoing reminder of how the ferocity of collectivity and interrelation shape queer and trans writing practices.

PM: Is there something you’ve observed about the collection after getting some distance from it that is surprising for you?

AA-K and KG: The anthology has met a readership that’s significantly larger than we imagined or anticipated: people are reading and engaging with it outside of the narrow confines of people who are currently trans or currently writing and reading poetry or currently engaged in anti-capitalist political activity. We’re 9 months out from our publication date and about to enter the third printing of the anthology; we’re reaching people we really didn’t expect to reach, and from that perspective we think we’re making an intervention of a scale that we didn’t anticipate. Which, like, word, that’s awesome.

One thing that that tells us is that people really responded to a collection of “radical trans poetics” who don’t often find themselves called to respond to any single one of those categories. We didn’t create that category ourselves: we responded to what we believe is an emergent structure—formally inventive, anti-capitalist writing by trans poets, whose experiments have something to do with political radicalism—and we used the anthology as a way to guide attention towards it. Our biggest surprise is that people paid attention to such a significant degree.

PM: What do you see as the next step or next iteration of this project, this book, collectively as it continues to reach readers?

AA-K and KG: We were recently corresponding with a friend and mentor who offered really generous praise for the anthology and said she couldn’t wait for volume 2. We don’t think that we’ve got another volume in us right now—not because trans writers aren’t continuing to produce incisive work, but because anthologies require a really immense amount of labor.

Something we’d actually love to see is for other people to take up the project of collating the cultural documents of trans radicalism. “Radical trans poetics” is a category that any trans writer could engage with—you know, in good faith—and now that we’ve done a substantial degree of work in trying to help make it perceptible to other people, our hope is that other writers, organizers and curators will feel like they can contribute towards it on their own—in volumes, zines, reading groups and reading series, whatever.

A lot of people have let us know that they’re assigning the book in their classes, and distributing the PDF to friends or students. That gives us a lot of confidence in the tenability of the overall project, and this pattern of distribution, which Nightboat made possible for us, meant that the anthology could circulate further than an ideologically or aesthetically similar project with more restricted access to distribution, catalogues, library purchases, fulfillment services and so on. That means that people have been able to engage with the forms of trans aesthetic and political radicalism in the book at a substantial scale outside of any one particular community or scene. We know that’s gonna spark something, although like with any project of radicalization it’s impossible at this juncture to determine precisely what.

______________________________________________________________

We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics edited by Andrea Abi-Karam and Kay Gabriel is available via Nightboat Books.