A Witch’s Rules of Matrimony

Lucile Scott on Myth, Faith, and Ritual in the Chaos of 2020

On Thursday April 2, 2020, at roughly 4:45pm, after a long work day spent dialing and failing to get through to unemployment, my partner Ellie, instead, received a call. The test results from a mole she’d had removed the week before had returned from the lab. It was melanoma. Staring blankly at a faded blobular stain on our Brooklyn living room carpet—a carpet that had, until four months prior been mine alone, I listened as the dermatologist calmly told Ellie to get to a dermatological oncologist as soon as possible. They needed to do a deeper removal and biopsy her lymph nodes to see if the cancer had spread.

Ellie works as a freelance theater director, and, as such, obtained her health insurance via the exchange. After she hung up the phone, Ellie and I quickly discovered that though it cost $737-a-month, this insurance did not seem to cover any dermatological oncologists at all—and certainly not the three her dermatologist had just recommended.

Elsewhere in New York City that day, 1,500 people died of COVID-19. Governor Cuomo warned that without intervention—ideally federal—our stockpile of ventilators could be exhausted in six days. Meanwhile, a White House coronavirus task force was in the process of determining not to launch a national COVID testing plan, as it appeared blue states were hit hardest by this new plague.

*

The first time I hexed a major national leader, I wasn’t sure how I, a more feel good sort of mystic, felt about ritual curses. However, the leader in question was Justice Brett Kavanaugh—and two weeks before the ceremony, Justice Brett Kavanaugh had received an appointment to the Supreme Court despite credible allegations of sexual assault and perjury. In the aftermath of the swearing-in that granted him a lifetime say in several of my more pertinent life choices, I’d developed an urgent need for an outlet, some communal cleansing flame of fury.

In most American—and other—mystic strains, the natural world, including each and every one of us, stands as divine as anything on high in the sky, and this belief has long beget radical notions of the equal right of all to a decent life here on earth—regardless of race, gender, profession, etc. The mystically-inclined say by tapping this divine source, one “become[s] less willing to accept powerlessness, or those other supplied states of being which are not native… such as resignation, despair, self-effacement, depression, self-denial,” to quote Audre Lorde, on how that transcendent energy, so sourced, can result in motivation to reshape the world.

The first time I hexed a major national leader, I wasn’t sure how I, a more feel good sort of mystic, felt about ritual curses.

At the group hex, in the backroom of a Brooklyn occult shop, I received the ecstatic dose of Pagan pageantry and poetry—complete with one goat skull, three large penis candles run through with coffin nails, and several Latin chants about justice—I sought. But I also discovered something more.

A fact I’d previously understood intellectually made itself felt in my blood: The communal rituals we undertake, each and every one of us—in a church, an occult shop backroom, a sport’s arena, a voting booth—and the world order they reflect back, shape us far more deeply than any treatise or plea to the rational mind. And a person, a culture, needs to be careful in how they deploy such potent magic.

*

As Ellie and I sat side by side on our couch, the “c” word a noxious gas cloud lurking, a certainty overtook me. I have excellent health insurance. I started Googling: Marriage license AND New York City AND coronavirus.

Assuming that I was Googling melanoma, Ellie asked what I had learned.

“I think we should get married.”

Ellie and I were set up a year-and-a half prior by my dear friend—who also happens to be my gay ex-husband. A decade before that, back when I was in my twenties and gay marriage was illegal in New York State, he and I had legally wed as part of a performance art piece. We intended the piece as an exploration of the institution as more capitalistic patriarchal construct than ritualistic communal signifier of a shared love cemented into a shared life.

However, to my surprise, like magic, the ritual worked. All the symbols—the dress, the procession, the vows, the rings, the kiss—cast their spell in our unconscious. We felt bound—in a deep, platonic way—diamond lock and key. Or as an attending friend later put it, “Shit got real in there.” Still, I thought that would be my lone tango with the marriage industrial complex.

The communal rituals we undertake, each and every one of us, and the world order they reflect back shape us far more deeply than any treatise or plea to the rational mind.

April 4, 2020 found my soon-to-be wife and I standing, in white, in front of our conglomerated house plants staring at an aging MacAir bearing an “I Voted” sticker, as a handful of loved ones watched our wedding ceremony on Zoom. Our lone live witness was my 16-year-old miniature pinscher Vinni. His position as best dog/dog of honor seemed fitting however, as, until I met Ellie, he was probably the living being I was closest to on earth.

It was then that I started thinking about several old or dead Europeans.

“Every culture can be considered as a complex of symbolic systems, in which language, the rules of matrimony, economic relations, art, science and religion rang foremost,” wrote French social anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss.

I started thinking about this at the outset of my own nuptial plunge into our symbolic order, because, with the country in freefall, I’d been thinking a lot about how—and if—cultures can truly change.

“It is not a matter of toppling that order so as to replace it—that amounts to the same thing in the end—but of disrupting and modifying it, starting from an outside that is exempt, in part, from phallocratic law,” wrote French feminist psychoanalyst and philosopher Luce Irigaray.

Returning to Lévi-Strauss: “I therefore claim to show, not how men think in myths, but how myths operate in men’s minds without their being aware of the fact.” Such is the power of ritual’s more verbose sibling—myth—to shape people’s choices and culture, even when they believe themselves free of its sway.

Of course, Ellie and I had little time to methodically devise a subversive ceremonial stone in the cyclops eye of patriarchy. We spent the majority of our 48-hour engagement figuring out how to obtain—then obtaining—a marriage license amidst a full New York State lockdown. Answer: Rent a Zip Car, drive to Connecticut, and stand in the entryway of a shutdown Town Hall, where a very nice masked woman named Barbara will bring you a license to sign with a Purell-ed pen.

I started thinking about this at the outset of my own nuptial plunge into our symbolic order, because, with the country in freefall, I’d been thinking a lot about how—and if—cultures can truly change.

Still, though a rush job, we did our best to divine a ritual “outside phallocratic law” and evocative of the mystic order of equality. We invoked no authority higher than the candle flames burning amidst our thicket of house plants. With no rings available for IRL purchase during lockdown, we bound our hands together with a thin knit scarf, literally tying the knot as they supposedly did in Pagan days. Then, with our hands tethered, we jointly lit a large white candle “to signify our new shared life and future, and that, with our lights combined, we will serve as a point of light in the world.”

Even this modified ceremony, undertaken in virtual communion yet physically alone with Vinni the dog, worked as ritually intended. I felt a new bond between Ellie and I—and that bond makes me feel somehow stronger.

But soon the post-ritual glow faded.

I’ve spent much of my adult life writing about AIDS—which has provided me with the aforementioned stellar health insurance. I’ve learned that viruses don’t just exploit weaknesses in an individual’s system. They exploit the same in any society or community they permeate. As such, it grew clear to me early on that, despite the rhetoric, we were not in fact all in this new pandemic together; that certain Americans, namely Black and Latinx ones, bore the brunt of this disease.

By popping a system’s weaknesses into high relief, a virus presents a choice. However, I felt less than optimistic that, given the political givens, there would indeed be a silver lining, some positive creation to be spun out of all the destruction, some sense of the redemptive narrative, a lesson learned. My sorrow regarding the state of the nation soon hardened into something darker. Then, 13 days after the wedding, as coronavirus deaths peaked in New York City, my dog Vinni passed on to another plane.

I read somewhere that the cruelty of grief is that the world does not stop for your pain. In spring 2020, however, the city that never sleeps had been all but frozen in place. The pause included most non-COVID-related medical procedures. We still did not know if Ellie’s cancer had spread.

With no communal ritual of cleansing rage available to us while in lockdown, my despondency soon settled into what some might call depression. I signed up for an online witch class. But by then the short-lived sheen of Zoom living, and connecting, had worn off, so I adopted a new, socially-distant ritual. I started taking daily pilgrimages to Prospect Park to see two swans who had built a nest in Turtle Pond. Every day, seeing this electric white duo felt like watching a full moon rise above a typhoon. At least for a time.

It grew clear to me early on that, despite the rhetoric, we were not in fact all in this new pandemic together; that certain Americans, namely Black and Latinx ones, bore the brunt of this disease.

I still felt myself drowning in all I could not see, but felt in quarantine—the people dying, suffering, broke; the floor that had fallen out for so many New Yorkers, and Americans; the fact that no stroke of a pen on an existing government paper could even start to fix it, as a marriage license did for Ellie and I, two middle-class white women. How badly did we all, and all we put faith in, have to fail to get here? And how do we stop falling?

*

On May 22, we found out Ellie’s cancer had not spread. On May 30, I went to my first Black Lives Matter protest of the year—while across the country once-mythic, now-denuded idols of stone and bronze fell like white-supremacist dominoes. Out on the Brooklyn streets, in our inaugural public outing as wives, the two of us never quite shoulder to shoulder with thousands of people, all masked but shouting, I finally felt that cleansing flame of fury—and all its accompanying power to reshape the world.

Because peaceful protest, like voting, contains a transformative ritual potency—at least if we maintain enough faith in the system that we think it can. Its spark already catalyzed a deep 2020 reckoning. Time will tell if it will conjure a re-casting of the white “phallocratic” American myths and rituals that got us to this broken place to form Americans myths and rituals that finally reflect and include us all. But out there in the hot late spring, amidst all the rage over all the death that never should have happened, but also amidst the shared faith that together we could still create a better future from the rubble, I felt something that I can only call hope.

Eventually, the heat of summer broke as the nights began to edge out the days, and the nation’s still disease-ravaged eyes turned towards the next battleground: an election under siege. An attack on our annual fall ritual of freedom aims for far more than a fix on its outcome. It aims to snuff out all the personal liberty and power casting a vote that will be counted conjures.

Back in Brooklyn, Ellie and I finally got around to buying rings. As we slid the gold bands onto one another’s finger for the first time, we took a second vow. It included: “doing our own small part to keep the flame of fury burning through the coming winter.”

__________________________________

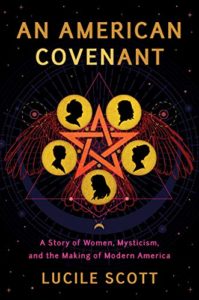

An American Covenant by Lucile Scott is available now from Topple Books.

Lucile Scott

Lucile Scott is a Brooklyn-based writer and editor. She has reported on national and international health and human rights issues for over a decade. Most recently, she has worked at the United Nations and amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research, and has contributed to such publications as VICE and POZ magazines. In addition, she has written and/or directed plays that have been featured in New York City, Edinburgh, and Los Angeles. In 2016 she hit the rails as part of Amtrak's writers' residency program. She hails from Kentucky and moved to New York after graduating from Northwestern University. An American Covenant is her first book.