A Shipwrecked Mother Tongue: On Confronting Linguistic Dispossession

Claudio Lomnitz Examines Inherited Languages and Family Histories

My mother arrived in Tuluá, Colombia, from Europe in 1936. She was four years old then, and at that point she stopped speaking altogether. Larissa had spent her first two years in Paris, and the following two in Nova Sulitza, Bessarabia, which was then part of Romania. During her early childhood, she had regularly heard Yiddish, French, Russian, and Romanian. I imagine that she spoke some mix of all of these languages, maybe with some predominance of Yiddish.

When her family brought her to a new place that filled her ears with yet another language (Spanish), she gave up trying to find any consistency between all of those languages, and just stopped talking altogether. She remained mute for an entire year, but afterward she quickly came to find herself in the Spanish language as if America had always been her destiny.

My mother effectively distanced herself from Yiddish and Russian before even fully learning them, and it is for that reason that she did not teach these languages to her children. I don’t blame her for this, yet it is undeniable that I failed to learn two of the languages more or less indispensable for writing this book: Russian and Yiddish. The loss of Yiddish, especially, was simultaneously the symptom and the effect of the dismantling of the Jewish community—how could my mother have retained it while growing up in the Colombian provinces? In all of Colombia there were then fewer than 4,000 Jews, and in some of the towns in which she lived—Sogamaso, for example, or Manizales—hers was practically the only Jewish family for miles.

My father, for his part, had adopted something of a chameleon’s strategy. He was a natural linguist. Even so, it was Cinna who denied me German, the third of the four key languages that I lack for this book. In effect, he refused to extend a bridge to the terror and ingratitude that he and his parents had left behind. I imagine there was a sensibility at work that resembled one of the rules of kashrut: “You will not cook a calf in the milk of its mother.” That is, if you’re going to eat the calf, you must at least allow it some dignity and not cook it in the milk of the one who loved it most.

My father observed a kind of inverted corollary of this rule, which might be expressed in the following way: You will separate your son from the language of those who wished to exterminate him. It was in this way that I lost three languages before I even learned them: I lost Yiddish and Russian because of their new status as excessive and unassimilable, and I lost German because of an inclination to avoid cruel or unholy mixtures.

Finally, unlike my grandfather Misha and my parents, I failed to study Hebrew. In the end, my parents did not send us to Jewish schools, and I have never lived in Israel. I did manage to learn the beautiful letters of Hebrew when I studied for my bar mitzvah. I know the form of the language, but I do not understand it.

Born in a sea of linguistic dispossession, I retained a bit of my father’s imitative facility. I also have his enthusiasm for phonetics and a certain semantic intuition. I learned, also, the exemplary capacity of forgetting that was practiced by my mother, her pragmatism. For me, linguistic displacement is a mark of origin. When I was five years old, I learned French at the Alliance Française in Santiago; at seven years old, when we moved to California, I learned English and forgot my French.

My mother tongue is a linguistic shipwreck; and it is from there that I write the story of my grandparents.

From that moment forward, I have remained sandwiched between Spanish and English, feeling comfortable to a certain point in each of these languages, but also insecure in both. Spanish is my Yiddish, and English is my Esperanto, but I have always lacked the perfect language: the one that names things without distorting them. For me there is not, nor can there be, a language of Paradise such as those possessed by the truly great writers, who make their homes in their language. My mother tongue is a linguistic shipwreck; and it is from there that I write the story of my grandparents.

My father knew a lot about geology, and, according to his point of view, South America is an immature continent. The Andes were to him dizzyingly dramatic. “Mother of stone, foam of condors,” as Pablo Neruda put it. As a geophysicist, he did not find peace amidst such deep stirrings.

When I was four years old, we took a family trip to Peru. Among my memories of the journey is a stop in Arica, as well as a nauseating plane ride to Pisco. I preserve in my mind an image of the red-chalice desert of Atacama and of the Morro de Arica, the site where the Peruvian colonel Alfonso Ugarte threw himself into the abyss rather than surrender to the Chilean army. And the taking of the frigate El Huáscar in that same War of the Pacific (1879–83), when the Chilean military beat Peru and Bolivia and appropriated their southernmost provinces… In those days, we boys still played with lacquered lead soldiers, and as a proud Chilean all of this fascinated me.

I remember also an afternoon among the cliffs of the Antofagasta coast, walking with my brothers, looking for anemones and starfish. The sun-filled and freezing Pacific snorted up between the slender tongues of perforated rock. An octopus hid itself in the whirlpool.

Later, in Lima’s Chorrillos neighborhood, I read a plaque commemorating the struggle of the valiant Peruvian people “against Chilean barbarism.” I was four then and read rather slowly, so that when I finally came to the part on the Chilean invaders, I cried out in disbelief, “Mami, it says here ‘Chilean barbarians’!” (We, good-hearted Chileans, were barbarians?)

In Lima, we also visited an archaeological dig. My grandfather Misha was there, though I don’t recall how he got there or why. He knew the archaeologists, or at least he knew how to approach them, because they allowed us to touch the cloth that covered some mummies that they were removing. I remember them giving him a strip of that ancient cloth, although I might be mistaken about that. This was my first contact with the magic of antiquity. The dryness of the Peruvian coastal desert can preserve cloth for hundreds and even thousands of years, and it was possible to touch that cloth, to interrogate it!

My grandparents did not accompany us to Cuzco nor on the rest of that trip, because of Misha’s heart condition. There was once a photograph of my grandfather at that spot, but now I can’t find it. I substitute it with another, of the selfsame Misha, but young and in a different locale in Peru. He has in his lap a skull, as if he were Hamlet posing with a pre-Incan Yorick.

To be or not to be indigenous? Or better put, as the great Brazilian modernist Oswald de Andrade would write at around that same time, “Tupí or not Tupí?” Was this perhaps the question my grandfather was asking? I doubt it. More likely, as the committed Jew and Marxist that he was at that time, he was inclined to see the present reflected in the mirror of Incan glory. Today’s Indians, though subjugated, would once again become great. Though imperiled, the Jews were also once again becoming great. This was the source of his energy and enthusiasm for Hebrew, as well as for his passion for the emancipatory spark that he intuited in indigenous communalism.

My grandfather was not then a wavering prince like Hamlet; rather, he was a man compelled to create a future out of a present that was always precarious, and from a past that was crumbling around him. For him, the idea of a new world was a necessity. His idea of America had less to do with nostalgia for the past than with a reality that needed to be achieved. Our America, the America of my family, was a necessary place that one must inhabit and defend.

Even today we still live in a dangerous world that is constantly asking us to make decisions, yet we can only face our collective dilemmas by way of encrypted personal stories. Because, as Walter Benjamin put it, to tell the past is to take ownership of a memory “just as it glimmers in the instant of a danger.” Thus peril is at once collective and deeply personal.

We are no longer governed by tradition, so we can’t simply rely on a collective past. For this reason family history is again relevant. It is no longer an aristocratic incantation of the glories of a lineage, but very simply our precondition: a matrix of past decisions that made us possible. And we stretch back to those decisions in moments of danger, as if we were migratory birds, flying in formation toward the south.

__________________________________

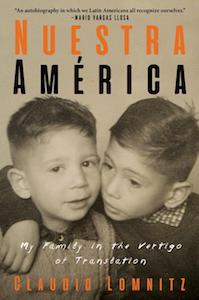

Excerpted from Nuestra América: My Family in the Vertigo of Translation. Used with the permission of the publisher, Other Press. Copyright © 2021 by Claudio Lomnitz.

Claudio Lomnitz

Claudio Lomnitz is Distinguished University Professor of Anthropology and Historical Studies at the New School University. His work focuses on the history, politics and culture of Latin America, particularly Mexico. He is the author of Exits from the Labyrinth: Culture and Ideology in Mexican National Space and Deep Mexico, Silent Mexico: An Anthropology of Nationalism.