A Season to Set the House on Fire: On the End of a Marriage

Elaine Bleakney Navigates What Remains

1.

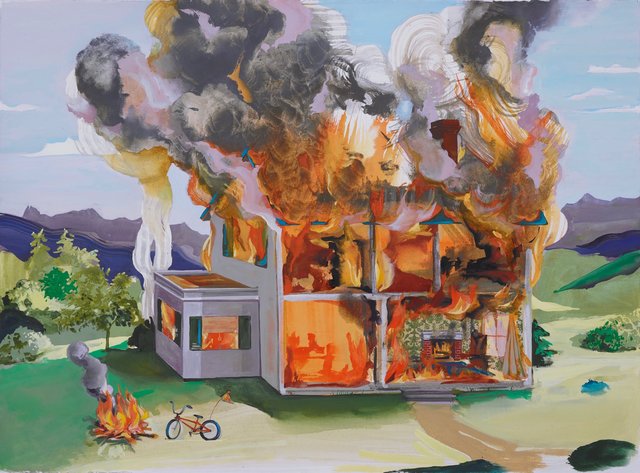

This is a drawing by Margaret Curtis. I saw it last June in a gallery in Asheville, North Carolina, where I live. Like many people at Curtis’s limited capacity, socially distant opening, I hadn’t seen art in a gallery for months. I froze when I saw this piece. I couldn’t move away. This was fine: no one edged in to usurp me. There was almost too much space. We were masked people, new at being out and looking at art, again. We had all signed up for our slice of time with Curtis’s work on Sign-Up Genius. I stood at the drawing, swaying like I do sometimes when I’m really present.

Margaret Curtis, Nostalgia (2020), Gouache and charcoal on paper, 22 × 30 in, courtesy of Tracey Morgan Gallery

Margaret Curtis, Nostalgia (2020), Gouache and charcoal on paper, 22 × 30 in, courtesy of Tracey Morgan Gallery

Life had changed and I had changed my life. Some weeks before the pandemic started, I had separated from my husband, moving with the help of friends out of the family house. My son, age ten, started traveling between two houses. He did this in such a fresh and eerily open way, once the zero hour had passed. I had moved down the road, just past the park and the synagogue. The house quickly became my house, a crying house, a laughing house, a home-school house, house of articulation and difficulty, harboring a different version of life under an oak and a hickory and sugar maple.

2.

The solid family house: someone has set it on fire. I wanted to buy this drawing immediately. It didn’t have the little red dot next to its placard. Margaret Curtis was there, in the room. I had only met her once; she is slight and spry and electric. She was talking avidly with someone she knew. I was talking avidly with myself, the day after, wondering how to buy the drawing. I could sell something? I could work out a payment schedule with the gallerist? I could write a letter to Margaret Curtis? I didn’t have the money. I thought about it for days and then a friend told me they had returned to the show and there was a little red dot next to Margaret Curtis’s “Nostalgia.”

3.

Relief. In my brief fantasy of owning the drawing, I had stepped inside. I had stood on the edge of a road, mesmerized by the burning vision below. It churned in me. This wild painting-drawing, gouache and charcoal. The colors of goldfish and citrus. The cool blues and greens of the tamed landscape. Too tame. The trees: new plantings, the old growth razed. Delicious flames overtaking the white house, the only house there. An Egglestonian red bicycle with a jaunty little flag, intact next to a campfire. A campfire? The front wall missing, each room agape and engulfed in orange: this is a doll’s house. A tiny person has composed a tiny fire in the tiny fireplace.

Before we plumb for our own words, we find safety. I stopped in front of Curtis’s house on fire and swayed.

Curtis made “Nostalgia” in 2019. It is not her only recent work of arson. Standing with this one, I experienced the aftermath of a woman screaming. Her voice hoarse. The crying done, clarity on her tongue. She tells her friend: I cried and screamed in order to feel heard. And I didn’t feel heard at all.

“My work has always been concerned with power,” writes Curtis.

4.

“What are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?” writes Audre Lorde. The prospect of dying from breast cancer delivered Lorde to the formation of her urgent speech, “The Transformation of Silence Into Language and Action,” given to attendees at the MLA’s Lesbian and Literature Panel in 1977.

To work toward words one does not yet have takes safety and time. To work toward words one does not yet have as a Black lesbian feminist in the 60s and 70s must have taken a safety like no other. By “safety” I mean a makeshift of love and support, like the love and support Lorde builds in her speech for us. By “safety” I mean the feeling that others have been here before and created a place to pause and listen. Before we plumb for our own words, we find safety. I stopped in front of Curtis’s house on fire and swayed.

5.

So my word, the word I dive for here, is sway.

To swing slowly and rhythmically back and forth from a base or pivot. I found the sway in my pelvis, 2010, holding my infant son. Sway: to soothe his body and brain. Soothing him soothed me. I found my base in my new mothering body: my two feet on earth. I swayed and when he was grown out of my arms, when swaying was done, I found myself swaying when I would meet mothers and fathers and their tender new babies. I found myself swaying in situations where I felt challenged or moved. I found I knew how to move. I started swimming, seriously, when my son grew out of my sway. Swimming is swaying, aloft.

An oscillating, fluctuating, or sweeping motion. Swimming, swaying, for me, entailed a not-speaking. A way to work with and work through silence and material. But I didn’t know I was doing this. I spoke about my anger in private with my husband and in couples therapy. I entered the spaces where betrayal and decay I experienced in the relationship could be worked on. Should be worked on. And within this language-making space I adjusted and limited my anger, even in the assurance that the expanse for it was there. Even when my anger was being reflected back at me, word for word, in my husband’s mouth: something wasn’t right; something important wasn’t happening.

Like many married people in dire straits these days, I read the Belgian-born psychotherapist Esther Perel, who advises one to let up on the idea of a perfect partner. She borrows from the language of capitalism to suggest “diversifying your social portfolio” outside of the marriage. I nested in this possibility. Had my romantic expectations become too rigid or high? Could I put some eggs in other baskets? Which ones? I diversified anew; I nurtured friendships to meet some of my needs. It worked, to a point where I was finally able to recognize within those friendships that the person I loved did not love me the way I needed. These were the words I needed to speak. I needed to say them, in safety, before I could see and say the harder thing: I no longer loved this person. In saying these things to him, in initiating our separation, he experienced rejection and cruelty. I experienced, over the painful months that followed, an annihilation of the trust we had formed. “Conscious uncoupling” it was not.

Sway: sovereign power, dominion. It took all my power to say no to someone that I had said yes to for years. As the months of aftermath wore on, grief nourished rage. He took up the position that he had always said yes; he had been working against my no and that he did not want to be treated as a doormat any longer. Okay, I thought. Okay. Our stories cleaved; our stories were cleaving and mirroring each other: this was what needed to happen in order for both of us to grow. But what to say of the notes I got from him—that I had been poisoned, that I was never the same in the marriage after this poisoning, and that he was done with the likes of me?

6.

The Trump egotocracy has hosted a landscape of fires small, large, contained, uncontained. Here so many of us are, angry and actively reckoning with ourselves and the injustices inherent in the systems and structures we have. Too many are casualties of these systems. Many, like me, are both casualties and recipients of the benefits of these systems. One need only watch Kamala Harris in her debate with Pence repeat the bit about “my friend, Joe” to feel the unseen pinch that bruises the skin.

In art, we find a way to be with the anguish. And we find others in the aftermath, living in parallel privacies.

There is so much confusion, challenge, and so much clarity. Lorde pleads for women to listen to each other:

And where the words of women are crying to be heard, we must each of us recognize our responsibility to seek those words out, to read them and share them and examine them in their pertinence to our lives. That we not hide behind the mockeries of separations that have been imposed upon us and which so often we accept as our own.

This is why Curtis’s drawing brings me peace, why I wanted to hang her drawing of a burning house inside my new, intact one. Here is a woman speaking, examining the house and the idea of home she has set aflame. Here is space for rage in the alchemical fire. Here is space to see and reject what pushes us down and gaslights and talks us out of our experience. Here is even space to save the little red bike, the child’s means of meaningful escape. There might even be space to laugh.

Curtis writes about her work as “autonomy won through confrontation.” In life, autonomy won through confrontation is a necessary, awful, anguishing process. In art, we find a way to be with the anguish. And we find others in the aftermath, living in parallel privacies.

7.

I write to the woman my husband was with after I broke with him. It was no secret that he would try with her, after he and I broke. She is lovely and open and wise. They were close for several years while I was with him. I watched, warily, fearfully, their closeness close in. I struggled. I even stood between them at one point.

I write to her because it’s fall now. There is change in the air (not hope, exactly, but something new, something clear-eyed) despite fear of the virus and the active forces of silence and tyranny and hate that have presented themselves as electable again. My son and I have a bag of winesaps to make apple pie. I don’t make pie. She taught him; he will teach me. I print a recipe out for the crust and filling but we barely refer to it. He grabs the soup pot and boils the apples we peeled. Dusts cinnamon, tosses sugar. The house smells like these good things. He shows me how she taught him. He remembers going to her house at the beginning of the pandemic, when we quarantined and were not seeing other kids. His dad would take him. Have you seen her lately? (I ask.) No, he says, he hasn’t gone to her house in a long time.

I write her an email. Thank you for the time you spent with him very early as he navigated his new fractured world.

She writes: You have no idea what it meant to me to hear that right now.

She writes: We just let him have unjudged creative space in the kitchen because it seemed like that’s what made him come alive.

Audre Lorde writes: …it is not difference which immobilizes us, but silence. And there are so many silences to be broken.

Elaine Bleakney

Elaine Bleakney is the author of For Another Writing Back (Sidebrow Books, 2014). Her writing has appeared in Kenyon Review, The Believer, and others. More of her work can be found at elainebleakney.com.