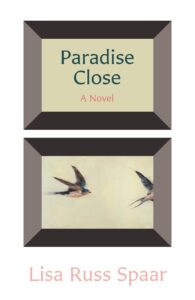

A Poetics of Risk: On Publishing My Debut Novel in My 60s

Lisa Russ Spaar Explores the Pleasures of Finding New Ground

I sit in an Adirondack chair and watch as my one-and-a-half-year-old granddaughter runs over to a nearby garden bed clutching a fistful of crackers. At the bed’s border-fringe of monkey grass, she stops abruptly, peering into the strappy shadows and shimmery coins of light cast by the noon sun on the canopy of weeping cherry and Japanese maple leaves growing there. Although I can’t see it from here, I believe she’s looking at the onyx stone statue of Buddha, who sits, deep in the garden, cross-legged, orant, at the foot of the weeping cherry.

During the prior winter, when R. was just beginning to walk, our traipses through the then dun yard, beneath bare trees, would often take us by this bed, Buddha hunched against the cold beneath a gray splay of cherry switches. Perhaps because they were about the same height—Buddha seated, R. toddling— she was curious but wary, not interested in getting any closer, in stepping beyond the tattered borders of the bed.

On this April afternoon, R. has been alive on planet earth for eighteen months, long enough to have experienced enough new “debut” things for the first time (in her infancy, my son-in-law mused about what embodied consciousness must be like in those first months—“like hallucinating constantly?” he wondered) to have developed memories, to recognize patterns, and to establish an incipiently stable self—along with the attendant awarenesses necessary to take a chance, to intuit or anticipate danger or consequence. Or pleasure.

R. steps carefully over the border of liriope and disappears into the garden’s shade. I wait. The air is full of finch song, the tea-kettling of wrens, traffic surf from the nearby road. When R. hurtles, laughing, out of the dark and back onto the bright lawn, I realize that I’ve been holding my breath. Later that evening, after R. has departed for home with her parents, I discover a gold crush of goldfish crackers in the cupped well of Buddha’s palm.

Risk is a complex phenomenon. In the sense of being “at risk”—of harm, danger, imperilment—we are, as homo sapiens, wired for it. While developments in civilization (medicine, technology, culture) mean that most of us don’t have to fear being eaten by wild animals or freezing to death or dying of an infection, we are at risk every time we cross the street or get into a car.

Often we are at risk and vulnerable to dangers of our own making—climate change, for instance, or political choice. “Risk-taking” involves volition, decision, and while sometimes reckless or self-destructive in its impulses, is usually driven by hopes of some sort of positive outcome—if not fame and fortune, then the satisfaction of having dared to attempt something outside one’s comfort zone.

The risks involved in writing poetry are different from the risks taken by skydivers or soldiers or medical care workers at the frontlines of disaster. They are, at least for me, also different from some of the risks involved in writing and publishing fiction. For the most part, the risks for the poet involve private concerns—can I confront my material honestly, ethically, morally? Can I find and wield language adequate to my experience? Can I make of it a sonically and lexically rich experience for the reader as well?

These questions hold true for writers of fiction also, of course, but perhaps because, with exceptions, the stakes involved in writing and publishing poems are fairly low (no life-changing advances, a below-the-radar public profile, with few reviews—and with those that do come in usually motivated more by admiration than malice—why bother to take down the work of a minor poet?), there is the illusion, at least, that one is working in poetry with what Emily Dickinson would call more “veil” than that afforded the novelist or short story writer, whose narratives can often seem very close to the life of the author, or at least prompt speculation about autobiographical connections, thus necessitating those caveats—“any resemblance to persons living or dead . . .”—that seem unnecessary in poetry collections.

The word “risk” derives from a Greek navigation term rhizikon, rhiza meaning “root, stone, cut of the firm land,” a metaphor for “difficulty to avoid in the sea.” Homer uses the term rhiza in the Odyssey to describe Odysseus’s treacherous sea journey and the protection afforded him as he hangs on to the roots of a fig tree. The term was used to refer to all manner of maritime dangers and possibilities, and was eventually borrowed into other languages with associations of daring, danger, consequence, undertaking, and hope. The word involves both the unknown (that potentially perilous sea) and the possibility of finding some new grounding (“root, stone, cut of the firm land”).

I began writing the pages that would eventually become Paradise Close, the novel—my first—that will be published this spring, nearly twenty years ago. I was middle-aged and already “established” as a poet, as much as anything creative can be considered “established”—one always wants to be growing, refreshing one’s praxis. I didn’t set out to write a novel. I didn’t know what I was doing. I knew simply that there were things I wanted to write about, to explore, that I wasn’t able to fit into or grapple with adequately in the kinds of poems that I was writing. In poetry, I’m something of a sprinter, working in short, sonically and lexically dense forms.

For the material that was haunting me—experiences from adolescence, nostalgia for certain places and people, concerns of early mid-life, and an accompanying age-inspired obsession with horology, with timepieces, with time and its slippages—I felt the need for more space, more duration, for the worlds these obsessions inspired to develop. I considered writing something autobiographical, a memoir, but finally found myself wanting to invent characters and scenarios beyond and (I hope) more interesting than the scope of my own personal journey; I began to write into ways of getting at more truth than my own memory offered up. Wading into the waters of literary prose felt like leaving terra firma, making the maritime origins of “risk” especially apt.

Although I was beginning Paradise Close in my 40s, I’m not sure I would have had the heart to risk giving it a life in the world even if it had been “ready” to do so then.So at first, the risk, for me, was the wading in, then treading water, then the diving down, coming up for air, periods spent hanging onto the figurative fig tree root of pause-and-reflect. Paradise Close grew in the interstices afforded by my fulltime teaching job, administrative duties, the exigencies of raising and launching three children, my poetry life (two collections of my poems and two anthologies of poems curated and edited by me appeared during the making of Paradise Close), I found myself working on not one but two prose “things.” I still wasn’t sure what they were, what to call them.

At one point, about six years ago I realized that the two stories “rhymed,” were related, and I spent a concerted summer trying to bring these parallel narratives together. When it felt that what I had made was actually a something—a “romance” maybe, a sort of fairy tale novel-ish?—the next question I had was: should I share this with anyone? Should Paradise Close have a home beyond my laptop?

By this time, I had entered my 60s. I’d been 39 in 1995 when Penelope Fitzgerald published her brief masterpiece The Blue Flower, a luminous piece of historical fiction about the Enlightenment poet Novalis and his ardent and inexplicable love for Sophie, a young girl. Fitzgerald was 79 years old at the time (her novel Offshore had won the prestigious Booker Prize in 1979, when the author was in her early 60s).

After re-reading The Blue Flower a few times in quick succession, I read as many of Fitzgerald’s other books as I could find. I learned that her first novel didn’t appear until she was 61 and that her literary career (as a biographer) had been launched just a few years before that. That one could commence one’s “career” or swerve into a new genre in the then to me unimaginable seventh decade of a life filled me with surprise and, I realize now, a strange kind of hope. Remembering Fitzgerald’s example gave me the courage to begin to see if my book could float, if it might have a life in the world and be worthy of finding readers other than myself.

Now that it has, or might, or will, my terror at emerging as a writer of fiction in my mid-60s is matched by a (re)new(ed) sense of freedom—to risk, to fail, to fail better—Beckett’s adage—which seems to me to also be the lesson of late middle- and old-age, just as this perhaps characterizes the risks taken by new human beings like R., daring to visit the garden Buddha.

Although I was beginning Paradise Close in my 40s, I’m not sure I would have had the heart to risk giving it a life in the world even if it had been “ready” to do so then. Fears of sounding sophomoric, rejection by critics, garnering the poor opinion of real fiction writers (many of them my amazing colleagues and students)—I’m not sure I would have been ready yet for any of those prospects when younger. But over the ensuing decades, larger losses and larger joys have diminished those reputation and career-related anxieties. Why not risk something new? If not now, when?

A few days after R.’s recent visit, after a day of heavy rain, I walk the yard, suddenly abloom with violets, picking up branches brought down in the storm. At the border of Buddha’s bed, I stop. The downpour has washed the statue clean. The goldfish crackers are gone, the upturned palm holding just a shimmer of water. Would it be corny to say that I set the purple star of a sawtooth violet into that small puddle? I’ll risk telling you that I did.

________________________________

Paradise Close by Lisa Russ Spaar is available now via Persea Books.