A Pilgrimage to Monk’s House, Where Virginia Woolf Found a Room of Her Own

Katie da Cunha Lewin on the Role of Writing Spaces in the Creative Lives of Virginia Woolf and Other Literary Icons

I can’t say how long it’s been there, but I have an image in my mind of the place where writers work. I picture the writer; I picture the space; I conjure an atmosphere of quiet calm in which someone can write for many hours undisturbed. This place contains a desk, on which lie various tools of writing, and perhaps a large window, out of which my writer looks to try to capture the world they depict. There are bookshelves teeming with dog-eared paperbacks, imposing hardbacks, critical anthologies, story collections, art books; my writer is also a reader, and a voracious one at that. They might sit on an old office chair, or one made of wood with a rounded back, but it has a squishy pillow nestled into it to keep the writer comfortable, and a blanket thrown over the arm, ready to keep them warm.

As well as the copious number of books, the writer of my imagination has art on their walls: postcards pinned and askew on a corkboard, prints hung up, and old film posters with a corner that flaps in the breeze. There are other smaller objects too, collected and curated to best inspire, full of meaning and sentiment; the potency of these objects lies in their creative charge—their inherent inspirational potential just waiting to be drawn out through the process of writing. These objects crowd shelves, hang from the door frames, peek out from behind books, or simply sit next to the writer as companions and friends.

Sometimes they can become talismans, items of good luck, or part of the ritual of the day, given a pat or a stroke. The writer’s room need not be neat, could in fact be the one space of the house where things are supposed to be messy, to show a mind at work. Proper creativity makes for unkempt spaces. Are there crisp packets or orange peel littering the desk? Discarded tissues, unstable piles of books unread, crumpled papers? No writing room can be pristine, but the detritus must not outweigh the buzzing, trembling atmosphere of solemn, serious work.

The room tells me that they know what they are trying to make, it needs only for them to catch the creative wisp and fix it down in words.

But what of the person themselves? They are less clear in my mind, a fuzzy outline. What I do know of my imagined writer is that they labour at their work. They are a conduit for that atmosphere they have made, sitting at their desk with a straight back, the pose of the concentrated. They delve into their work, not looking up from the page or the screen for hours at a time. They are a figure of certainty and of authority; the room tells me that they know what they are trying to make, it needs only for them to catch the creative wisp and fix it down in words

*

The idealized version of a writer’s room arrives as an idea not only through its depictions in art, literature and in the media but also as the very real spaces that are often contained in museums and preserved writers’ houses and make up one part of a display about their lives. Literary tourism is a profitable industry and most capital cities have several preserved house museums to lure the bibliophile. An intrepid literary explorer can take a trip to the houses of John Keats, Thomas Hardy, Fernando Pessoa, Jean Cocteau, Emily Dickinson and Louisa May Alcott to name but a few.

Though the houses are all very different, depicting different time periods and living styles, an emphasis is often put on maintaining the room in which the writer wrote, recreating it, or presenting a composite version of many different rooms the writer may have worked in throughout their lives. As the academic Nicola J. Watson suggests, literary tourism “materializes and individualizes reading as remembered experience of place,” linking the books we love with the writers who were working in particular houses, settings or rooms. We are reminded, in these spaces, that writing does not just happen, but has to happen somewhere.

But what pulls us to the writer’s room, to Charles Dickens’s study at the Charles Dickens Museum in Holborn, London, for example? Are we looking for evidence of genius in his pen and inkwell, or somewhere behind the blue jug decorated with black olives and green leaves? Or is there something murkier here, the leftovers of words or ideas secreted behind the picture frames or even in the very walls themselves? It can feel almost prurient visiting the famous houses of celebrated artists: at Sigmund Freud’s house in Hampstead, his books line the crowded shelves, his collection of antiquities sit in a glass cupboard, and yet Freud himself is not there to mediate or to explain their significance. As I’ve wandered around a writer’s house or museum, I sometimes feel as if I’m trespassing, entering a place where I shouldn’t, looking at the objects that make up a life, objects instilled with so much more significance than they can communicate through a quick glance.

On a mild, sunny day in April, I make a trip to Monk’s House, the cottage of Virginia and Leonard Woolf. Bought by the National Trust in 1981, the house has been preserved so that is looks just as it did when the couple were in residence: vibrant paint on the walls, original furniture, Leonard’s favorite flowers filling the garden. Though I have many questions about the mythologizing of the writer’s space, there is still something incredibly seductive about the idea of actually being in the home of a genius author. And there was a small part that hoped it might spark, if not genius, at least inspiration, for myself.

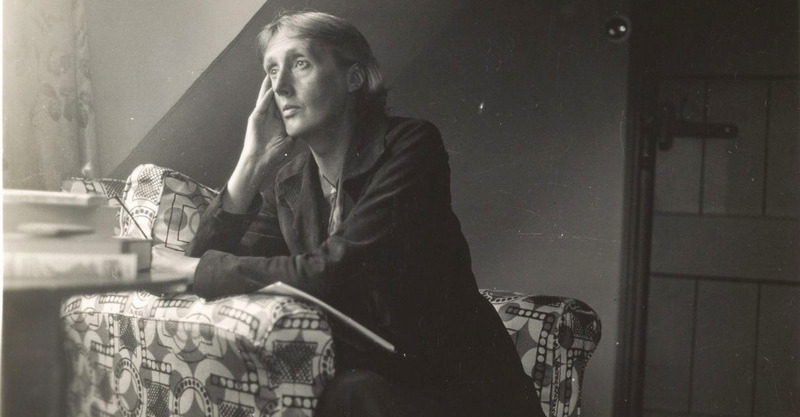

Woolf’s name is so familiar that I’ve forgotten where I first learned of it, or her work. Perhaps it was the year I received from my parents a collection by Penguin Modern Classics of works that have been adapted into films: Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, E.M. Forster’s A Room with a View and Woolf’s 1928 book Orlando. Woolf’s name accompanied me through university. Reading To the Lighthouse in the third year of my undergraduate degree, and again during my Masters, Woolf was inscribed into my academic life as someone indispensable, someone who provided ways of understanding what it means to be alive. When in 2014 the National Portrait Gallery hosted an exhibition of Woolf portraits, painted by people such as her sister, Vanessa Bell, and Roger Fry, I attended with Susanna, one of my best friends.

As we walked around the gallery, we were surrounded by Woolf’s image, often in the pale washes favored by the Bloomsbury group; my favorites were of her reading or sitting near piles of haphazardly stacked books. I found myself made more curious; I wanted to know what she was reading with such attention, and to peek into her rooms; I wanted other ways to understand how her writing came to be. I bought a print from the gift shop, one of the most well known of her portraits taken by photographer George Charles Beresford, in which she looks impossibly young and elegant. Here she is twenty years old, her long solemn face looking slightly down and out of the frame. I always read it as an image of beginnings, which felt appropriate given my own age then, only a couple of years older than Woolf in the portrait, with serious aims and ambitions, though without direction. This is Woolf while she still had the second name Stephen, her books yet to be written.

On the day of my visit to Monk’s House, I felt nervous on the train as I watched the English countryside fly by in smudges of green. I knew I wanted to get something from this trip, but what specifically? I was hoping to find the house beautiful and moving, to feel excited by sharing a space where Woolf had once been, standing on the same bit of floor, or gazing out at the same view. More practically, I wanted the trip to give me ideas, to be full of possible directions to take my writing. And, most embarrassingly, I hoped for some gorgeous Woolf paraphernalia, like a beautiful illustrated image of the house or something simple like a tea towel. I wanted a keepsake, even if it was mass-produced and ultimately unimportant. I had the sense that there was something significant about visiting the home of a person I admired greatly, though it was hard to put my finger on exactly what that was.

Nevertheless I was treading a well-worn path, journeying to a place of note in the hope of finding some trace of one of my most beloved writers. Woolf herself seems to have been aware of the fraught nature of this desire, even in the very earliest days of her career. As she wrote in her first published—though anonymous—piece for the Guardian, “Haworth, November 1904:”

I do not know whether pilgrimages to the shrines of famous men ought not to be condemned as sentimental journeys. It is better to read Carlyle in your own study chair than to visit the sound-proof room and pore over the manuscripts at Chelsea…The curiosity is only legitimate when the house of a great writer or the country in which it is set adds something to our understanding of his books.

In this essay, Woolf explores her interest in going to see the parsonage, the home of the Brontë siblings in Haworth, West Yorkshire, partially spurred by her reading of Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte, in which both the Brontës’ home, and the nearby town of Keighley, provide a backdrop to the lives of the family. Yet it remains unclear why one preserved writer’s house may “add” something to our grasp of a writer’s work—thus making a trip there “legitimate”—while others may not. As Woolf goes on her visit, she finds the town almost ignoring the visitors that are there to look for traces of the sisters (not so today), and out of their uninterest finds some greater sense of authenticity. Without the interest of the locals, Woolf finds that “our only occupation was to picture the slight figure of Charlotte trotting along the streets in her thin mantle.” Later, when Woolf arrives at the house itself, she is reassured that it is, for the most part, unchanged: what Charlotte and her siblings saw each day, she does too. For the young Woolf, “legitimate” seems to suggest a past made visible and legible, in which a visitor can think of their writer in their setting unencumbered.

On my visit to Monk’s House, I found myself looking for the same, a way of visualizing Woolf in her home that felt true. After taking a cab from Lewes station, I walked down a quiet road, and found a few people milling outside a green gate. These were my literary compatriots, out here for reasons unknown. My dreams of tasteful objects for purchase were quickly dashed when I was greeted with a very simple room in which a National Trust volunteer stood smiling behind the counter; the space had whitewashed brick walls and, charmingly, still gave out old-fashioned tickets, as if I were visiting an old cinema or were taking part in a raffle. There wasn’t any Virginia Woolf-themed fragrant soap or notebooks emblazoned with her face, but some titles relating to Woolf, the gardens of the house and the Bloomsbury group were for sale, alongside a nice collection of second-hand books, very reasonably priced.

The house was a simple building when they bought it, without running water or electricity. Woolf seems to have been charmed by this apparent modesty, finding it “an unpretending house, long and low, a house of many doors.” She liked the pace and freedom of the life they lived in the country, such a contrast to the intensity of London. The building has kept some of this lightness of feeling all these years later, smallish and airy, its multiple exits and entrances providing the possibility of spontaneity.

Though I listened to the words of the volunteers as they told us a little about this place, I walked around the lower floor of the house (the top floor is not open to the public) in a kind of daze, floating from room to room, thinking about the writer who had been there too. I imagined Woolf’s voice echoing around the walls, her seated in a chair by the fire, or walking over to the bookshelf and selecting something to read. I couldn’t help but notice the decoration: the living room was a very bright mint green, a color that Woolf herself chose, and filled with objects such as tiles and table tops designed by her sister, the artist Vanessa Bell. Everything here was of characteristic “Bloomsbury” style—a rejection of stuffy Victorian design, dark colors and foreboding, stolid furniture and instead a celebration of the jumbled, the contrasting and the individual.

All preserved writer’s rooms, in which the experience is always to know that what we see is, in reality, a fiction.

Woolf had her own bedroom on the lower ground floor, with a separate entrance and large bright windows. Yet she did not work here for long. Instead, she ventured outside and into an outhouse onto which apples from the tree above would fall with a loud and distracting bang. This outhouse, very low-key in its arrangement and cold in winter, would later be transformed in 1934 to become a proper writing lodge. This was just one of a great number of changes the couple made to the house over several years, gradually altering the layout of the rooms and adding a bath and an oven as their fortunes improved, thanks to the increasing popularity of Virginia’s work and Leonard’s attentive book-keeping.

For the scholar Victoria Rosner, Woolf’s move from her room to the shed was important in not only the way it allowed her to claim her own space—after all so much of their income came from her work that she had clearly earned the right—but also as a way for her to signal her removal from the household: “writing outside the house was a way to isolate herself from interruption.” Or, as the British writer Jeanette Winterson neatly describes, it was a kind of “divorce from domesticity;” Woolf’s journey elsewhere, even only a few meters, allowed her an important psychological distance from the rules of home.

After Woolf’s death, the writing lodge was extended to become a larger studio for Leonard’s new partner, Trekkie Ritchie Parsons, an artist. Today, half the room stands behind glass while the other half is open, displaying various photographs of the individuals that visited Leonard and Virginia during their time at Monk’s House. Woolf’s writing desk sits behind the transparent pane, recreated as a messy scene of writerly industry, with crumpled paper, a vase filled with daffodils, and various covers of her books, again designed and painted by Vanessa (who did so many of the covers for their Hogarth Press), strewn across the desk’s surface. The contrast between the apparent haphazardness of the desk and the polished glass makes the scene feel oddly stilted, almost too composed, as if we look at a curiosity in a zoo.

Jeanette Winterson wrote of her trip to Monk’s House and also found this set up strangely alienating, calling it “the most disappointing room [that] yields nothing of the atmosphere of [Woolf’s] writing life.” As Woolf did with the Brontë siblings, so Winterson looks for legitimacy and authenticity in the home of the writer she so admires. But in the staginess of the scene, she feels only the lack of Woolf: “she is long gone. The sense of someone else having taken over the space is all too pervasive. Here is the writer behind glass, mummified, invented.” I didn’t feel that sense of disappointment quite as strongly as Winterson, but there was certainly something strangely lifeless about Woolf’s shed. Maybe what Winterson describes is not only the experience of this room for her, but all preserved writer’s rooms, in which the experience is always to know that what we see is, in reality, a fiction.

In spite of these feelings, and the noticeable absence at the center of the scene, I took a picture on my ancient iPhone. On the train on my way home, I studied the photo; it was unavoidably bad, slightly out of focus and obscured by the glare from the glass that no amount of angling my hand could avoid. Nonetheless, I didn’t delete it; it felt somehow that I had a piece of Monk’s House as long as the image stayed on my device. I’ll find myself, over the course of the months in which I’m writing this book, checking and re-checking it. Even in the knowledge that the room had not been quite what I wanted, I still took a snapshot as a souvenir, in the hope it would allow me some of its magic.

__________________________________

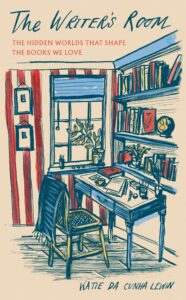

Adapted from The Writer’s Room: The Hidden Worlds that Shape the Books we Love by Katie da Cunha Lewin. Copyright © 2025. Available from Elliot & Thompson.

Katie da Cunha Lewin

Katie da Cunha Lewin is a writer based in London, currently lecturing in 20th and 21st-century literature at Coventry University. She holds a PhD in contemporary literature and is the co-editor of Don DeLillo: Contemporary Critical Perspectives. Her writing has appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, The White Review, Irish Times, Los Angeles Review of Books, among other places. She loves exploring issues of writing and the writer in the 21st century.