The people’s history of bathing is one of shared space. Histories and practices of the bath belong to histories and practices of the commons. Bathing routines are cultural rituals, architectural forms, and natural environments combined to make arts of living out of everyday necessity. The aquatic landscapes that make us want to jump into and splash about in—rivers, pools, waterfalls, springs, and sea—are where we have always washed and where we might like to immerse ourselves each day if we could.

References to these natural bodies of water persist in the most urbanized forms of the bath. Global migration shifts demographics so quickly that some of us find it increasingly difficult to say what exactly our culture might be, or to hold onto the threads of what was once felt to be a continuity. The reach of the human has so transformed the face of the earth that we can no longer identify what was once called natural.

Centered in the restless flux of our anthroposcene, bathing is a way to dive into the complexities of culture–nature tension up to the points of dissonance and dissolution. In Mohawk artist Melissa General’s 2016 video Kehyá:ra’s, we see her entering the Grand River over and over, collecting water in Mason jars. The audio is of her bathing in a traditional medicinal bath. This bath is both symbolic and literal.

Bathing in the river water of the Six Nations Reserve, she directly places her body at the center of a number of issues: the theft of Indigenous land by the Haldimand Tract, and its ongoing land claim; the pollution of the river upstream from the reservation by agriculture and industry that impact this downstream community inordinately; the multiple forced relocations of the inhabitants of the reservation; the river as the source of life and medicine for the community and for all of us; and the hope for healing her body, her community, and the many violently fractured relationships the landscape contains.

If artists and architects working with the forms of the public bath are in fact articulating relationships between people and creating sensible meanings to our relations with the world, we all are doing this each time we bathe. The baths we make are our creation, dreams of life we could live. The reverie we slip into as the warmth and water seep into us is no slumber, but a waking to our interdependence.

Spaces of communal bathing are of immense importance in a feminist history of architecture. For women whose relationship to public life has been historically tenuous, collective spaces connected to bathing, washing, and drawing water have been and continue to be spaces of organization and communication where gender-assigned unpaid domestic labor meets shared resources.

As architectural historian and material feminist Dolores Hayden observed in 1981, the privatization of domestic activities serves to further isolate women from each other, and prevent solidarity. The negative impact of this upon the commons is traced by Sylvia Federici in her descriptions of how women’s historically assigned roles have led us to become caretakers of common water and land by necessity. Public bathing spaces are set up expressly as sites in which we negotiate sexualized and gender-based division and behavior.

After bathing, I drink this same water from a rusty, mineral-encrusted tap, the smell dominating the strong taste of iron.My first visit to a hammam occurred when I was working in Carthage as a student in 1992, and it was an unforgettable experience. The cavernous stone spaces lit by tiny ceiling windows contained a delightful, energized social scene, in no way reflecting what I had seen in the public streets, squares, and mosques of the city, where the women were either silent or invisible. This was a special kind of public space, one that challenged the frameworks that I had been taught to distinguish public from private.

I came to discover that in every culture, the public bath functions for women in ways that address their subtly pervasive subjugation in the so-called public sphere. The endlessly nuanced forms of segregation and regulation in the gender-split baths and changing rooms of the world start to appear neurotic once placed in the broader history of bathing, where we can read prescriptive gendered behavior in changing room plans and the directed movements from entry to exit.

At times it seems that overemphasizing sexual differentiation has in fact been the program of the public bath in Western European culture for the past centuries. Their architectural forms reveal a more general history of suppression through endless forms of segregation where young and old, black and white, male and female, able and disabled, pure and impure, organic and inorganic, are constantly being classified in an exaggeration that betrays uncertainty.

As I soak in hot geothermal water in an old bathtub dug into the ground, I inhale a slightly rank sulfurous smell. The air is cool and clear, and I can see far out over the fertile fields and hillsides formed by ancient volcanic activity. After bathing, I drink this same water from a rusty, mineral-encrusted tap, the smell dominating the strong taste of iron as I force myself to take this other, inner, bath. I want to delve more deeply into the notion that ingestion and immersion are two sides of the experience of place, an experience I know very well when my eyes are closed.

At moments this analysis of architecture remains open to regression to the sensual apprehension of a child without censure. To enter the architecture of the bath, I feel the need to go back in a way that resonates with early life. The fact that throughout history the feminine has been given the symbolic burden of the material and the liquid cannot be ignored. Feminist and LGBTQ+ inquiry can loosen essentialist traps that allow us to glimpse alternatives.

Traditions have to be brought into awareness if we want to reimagine the bath with a different script, where we get a chance explore new, democratic, and emancipatory social potentialities. I believe that this loosening and questioning are precisely what public baths have always done and continue to do, and why they are of such importance to architecture now.

There has been a resurgence of interest in the design of bathing as a luxury travel destination over the past decades as high-profile architects have created spaces of immense architectural potency, such as the iconic Therme Vals by Peter Zumthor. In addition to these singular expressions of design excellence, there has been a parallel resurgence in public bathing as urban infrastructure, as postindustrial cities seek to reclaim industrial waterways for other kinds of development. These two phenomena are found here in juxtaposition with other less visible typologies of bathing architecture that offer instructive perspective on these trends.

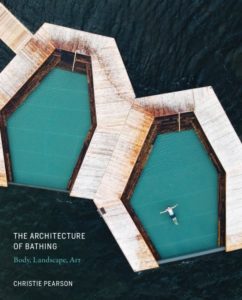

The title of my book, The Architecture of Bathing: Landscape, Body, Art, articulates terrain in which architecture could situate itself more deeply. The term architecture of bathing is used here in two senses. The first sense is the architecture that supports bathing activities, such as showers, swimming pools, saunas, or riverside steps. It is especially when these activities are shared that we recognize that they are of architectural importance.

As we look closely at these communal constructions, their inextricability from landscape forms, bodily practices, and cultural production emerges. This inextricability inscribes a responsibility into the production of architecture, critical of purely formal approaches, pushing the parameters of architectural discourse more deeply into our bodies and into the world.

The second meaning is a proposition to the reader for an approach to all architecture as if we were going to experience it as an immersive material and social space integrated into the vast, interdependent environmental and cultural fabric in which we are completely enmeshed.

We might ask ourselves at this moment why there has not been more writing on bathing from an architectural perspective, and why the terms bathing and architecture seem not to belong together. For the ancient Western writers on architecture, from Vitruvius to Alberti, spaces of bathing had their place in a major book about architecture, with import as essential public buildings and notable for their structural and mechanical innovations. This is worth recalling today, as many elements of the public are crumbling under neoliberal global capitalism.

In addition, architecture’s relevance falls into question when it ignores the care of life at the most basic levels, a source of mistrust of architects by the public in general. Just as Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ Maintenance Art Manifesto (1969) separates the work of development from the work of maintenance, the architectures that maintain would address the labor associated with washing, as well as childhood, old age, sickness, and health.

As a micropolitics, bathing is a quintessential practice of everyday life.The history of this field needs visibility, as Ukeles understood in creating her 1973 Hartford Wash performances that scrubbed the Wadsworth Athenian museum clean. Feminist philosophers such as Elizabeth Grosz have recognized that the body belongs at the center of the inquiry. The Architecture of Bathing contributes to this correction in challenging the still- dominant framework of heteropatriarchal and colonial/imperial assumptions that form the basis of much contemporary architecture, and tries to do so in a way that does not reproduce these structures.

Engaging queer, feminist, ecological, and decolonial critiques as tools for exposing decaying systems of knowledge and building gives us all more space to breathe. I speak in the first person to include my experience, ground my observations and speculations, and as part of a feminist practice of self-reflection with a rich history. I use images and quoted texts in a way that lets them speak for themselves directly, almost as irreducible material objects.

Each element of this strategy is intended to question and reimagine architecture’s scope. A history of architecture that privileges objects with clearly defined boundaries sitting on a site like a hat on a chair offers a desiccated carcass of what architecture could be. If this description seems exaggerated, it still maintains a deep hold in the education and practice of architecture.

There is no building without a profound connection to the world of which it is an intrinsic part and the experience of the people who use it. As the architecture of bathing builds itself out of complex interdependencies embodied in built environments, it reaches out instinctively toward post-humanist and eco-feminist philosophies.

As a micropolitics, bathing is a quintessential practice of everyday life. We want to take our time to look at the movements of our bodies, what we touch, how we feel, and how we are relating to those around us in the space of the bath. Experiencing architecture sensually, emotionally, socially, can be depressing as often as it is delightful, perhaps not as easy or enjoyable as it first sounds. We sense our awkward position, our fear of standing out, our sore ankle, the mildew in the grout, the harshness of the light, an unpleasant expression on someone’s face.

There is no ignoring the fact that my experience of architecture includes many subjective factors such as my race and the racial politics of the place I am in, my organic constitution and its biological interactions, my economic status and the economic systems I am embedded in, the social expectations I was raised with encountering those of others around me. In order to incorporate these into my understanding of architecture, I must write from my own experience.

I also look to the sociologist Henri Lefebvre (1901– 1991), in particular The Production of Space (1974) and Toward an Architecture of Enjoyment (posthumously published in 2004). Lefebvre offers a useful critique for notions of architectural purity, with a dynamic understanding of space as collectively created, and where political, social, and corporeal dimensions of space unfold only over time.

In this sense, duration is of great importance to the architecture of bathing. In addition, from a Marxist perspective, leisure space-time can critique the space-time of capitalist production in a mode comparable to festival and sacred space, and in relation to the biorhythms of all life.

We can locate some of the limits to Lefebvre’s socialist utopian vision in relation to our time. The more-than-human world needs us to expand our relationality to include all living beings on the one hand, and the material production of buildings on the other—methods of extraction, material production, transportation, use of labor, energy consumption, and building life cycles. Since the objectification and instrumentalization of the earth and huge portions of humanity is no longer tolerable to the conscience, architecture’s relational potentiality struggles to redefine itself at multiple scales, both smaller and larger than we may be accustomed to.

The design of buildings can learn from landscape architecture and art to address the most urgent issues of our time, envisioning environments that speak directly to the body, engaging dynamic ecological systems and natural sciences, and caring for life as a process. The many forms of the communal bath as architectures of enjoyment reveal that it is often enjoyable only for certain people, and unenjoyable for others.

Socialist bathing institutions such as the heroic Soviet banya need to be read alongside Russian novelist Mikhail Zoshchenko’s wry descriptions of the space in his Banya (1924). We often find bathing practices at the center of alternative and intentional communities of the 20th-century West: for example, the birthplace of the counterculture, Monte Verità’s vegetarian sunbathing and art commune in the Swiss Alps (1900– 1923), right up to the American communes founded in the 1960s such as Harbin Hot Springs in California, still in operation today.

When bathing practices contain blueprints for ideal mental and physical states, experiences, and forms, they leave trails of the disenfranchised and disenchanted. The promise of emancipation through a liberation of the body’s instincts and a reclamation of Eros as a collectively binding ethos built on natural desire and relation is less clear today as we struggle to absorb the full impact of anthropocentrism and colonial legacies.

While the desire to assert Eros’s capacity remains compelling, the search for an architecture of jouissance after AIDS presented us with another set of concerns. What the regimes of pleasure might offer us under neoliberal global capitalism is another question behind this inquiry, as we find the bath’s shadowy and sunlit spaces.

The goal of secular and sacred bathing environments around the world is regeneration in community.We enter the public pool, the sauna, or the beach with a heightened awareness of our own bodies and those of others. Bathing environments emphasize tactility and body awareness, literally bringing us closer to materials and bodies than we are in other spaces. The phenomenology of bathing opens all of our senses toward the physical world entwined with the social.

There is a theatrical dimension to the communal bath experience. The drama and festive excitement are equally clear when we look at a medieval painting of a town bathhouse complete with live music, food, and drink, or Lelf’s bacchanalian fantasy set in a contemporary version of such a space in his 2013 music video “Spa Day.” The setting and atmosphere are always charged with the potential for transformation, however quotidian. By undoing structured performances of identity and divisions between public and private, sacred and profane, purity and impurity, male and female, they continue to provide societies with space for testing behavior and ideas, and exploring new ways of being together.

The goal of secular and sacred bathing environments around the world is regeneration in community. More than merely articulating or critiquing existing regimes of power, they offer theaters for the reimagining of power dynamics. Forms and fashions in collective bathing change quickly, moving with the rapidity and ease of water as we pick up on subtle shifts in our social and environmental contracts reflected in an urgency to address the cultural moment in art and architectural works involving bathing.

Bathing architectures offer a set of instructive typologies rooted in cultural traditions that connect us to both prehistory and the sound of a dripping tap. At their most provocative, these environments show a profound engagement with both the natural world and formations of the social that carry tradition. The bathhouse, onsen, sauna, hammam, mikveh, jjimjilbang, gymnasium, and spa all continue to evolve to form meaningful spaces of rejuvenation and connection.

Water helps us make space tangible as sculptural material. Aquatic typologies and metaphors lend themselves to spatial reveries, giving us a fresh look at space as volume, flow, and movement. Architectures of bathing through necessity prioritize space, hapticity, materiality, atmosphere, relation, and polysensuality. Half metaphorical and half experienced, bathing architecture allows us to rethink the formation of space more generally.

Like water, space is filled with qualities, saturated in information and intention. The qualitative and quantitative aspects of space as a thing emphasize our permeability, our distance from others, how we live wedged between floor and ceiling. New materialist philosophies and actor-network theories leap into focus while we soak in the public baths, where we glimpse an ontological terrain of relation and interdependence which, like water, is always in motion.

Bathhouses can serve as institutions, heterotopias, counterpublics, and temporary autonomous zones, where the script can be continually rewritten by whoever shows up. `

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Architecture of Bathing: Body, Landscape, Art by Christie Pearson. Reprinted with Permission from The MIT Press. Copyright 2020.