A Living Ghost From the Chechnyan War

Wojciech Jagielski: "So many good men were killed . . .

all for nothing.”

Although he’d licked his wounds and escaped the jaws of death, Omar had never returned to the land of the living. They said in the gorge that although he was among them, he wasn’t really with them; he’d been too close to the brink to come back entirely. It’s impossible to cross the border between life and death and then go on living without paying a price for it.

He had moved out of Lara’s house and gone back to his relatives in the neighboring village of Birkiani, where there was room for him once the Chechen refugees moved out. But he hadn’t stayed there for long. He was altered somehow, absent, as if nothing mattered to him. Human affairs had ceased to interest him, he was indifferent to his neighbors’ quarrels, troubles, and poverty, and to the injustice they faced from various officials. But also to their joys. He didn’t seem to care about vengeance or forgiveness, war or peace. He had no opinion on any of these things. In the past, he had expressed his views like everyone else, but that was long ago, as if in a former incarnation. Now he had no urge to say what he thought about anything at all. Except perhaps the weather—if it was the right time to gather chestnuts or drive the cows and sheep from one pasture to another. He responded to everything with the sort of genial smile that adults bestow on ignorant children who haven’t had any experience of life yet. Sometimes he spoke so quietly that the words had to be guessed, and sometimes they were completely incomprehensible. Until finally one day he went into the mountains, where he now lived on his own, grazing the village herds of cows, sheep, and goats.

That was where I met him, at the herdsmen’s camp that had been his home ever since he’d turned his back on people. It was October, the season for gathering chestnuts, the last task in the fall. Once it was done, the Kists got ready for winter.

The herdsmen’s camp was in a small clearing among some hundred-year-old trees. Besides Omar, about a dozen families were here to gather chestnuts in the woods. The chestnuts were put into large, strong sacks, which every few days were taken down to the gorge by horse or in the beds of the old trucks the villagers used for expeditions into the mountains to fell trees for firewood and fetch building materials they could sell.

The chestnut gatherers and herdsmen lived in tarpaulin tents and shacks. Omar, small, thin, and wiry, wearing an army jacket and soldier’s boots, lived in his own cabin, which he’d built for himself in the forest. Some of the villagers had helped him, giving him whatever they had to spare in their farmyards that might come in handy—wooden boards, old doors and windows, panes of glass, and furniture. From the power plant on the river, they’d towed in a small shipping container that years ago had housed the workers renovating the dam. It served Omar as the skeleton for his home.

I was curious to set eyes on a man who has escaped the jaws of death and to see how it had changed him, but there was nothing unusual about Omar’s appearance. Withdrawn, as if shy, he flashed his gold teeth in a smile. But the people who had come here to gather chestnuts, both the young and the old herdsmen, obeyed him, compliantly carrying out the orders he issued in a soft, barely audible voice. Here, he was the boss, in charge of everything.

Every two or three days he went up the mountain to a larger clearing, where he stood on a wind-toppled oak tree to catch a cell phone signal. He checked the messages on his voice mail, which were usually to do with the packhorses he sent from up the mountain to a river crossing point to collect equipment, food, clothing, and tools for the camp. His water came from mountain streams. Sometimes there were calls to Omar from the gorge to announce guests, foreign tourists visiting the gorge who wanted to stay the night among the herdsmen and listen to Omar’s stories around the campfire.

After being wounded during the winter battle for Grozny, he had spent three days lying among the corpses in Minutka.

In spring and summer, some of the young men from the gorge were sent to live at Omar’s camp in the clearing, to help with the cows, sheep, and horses. They also made cheeses, and sheep’s wool felt for blankets, rugs, warm clothing, and hats. Some of them stayed up in the mountains for months on end, while others swapped places after a few weeks. Apart from school and work at their small family farms, there was no other occupation for the young men in the gorge. Because he hosted them at his clearing, Omar knew most of the Kists from the villages along the river. The young men came to his camp not just to work, but also to get away from the control of the elders and to have a good time together by the campfire.

When the chestnut season ended, Omar was left alone in the mountains. If he could, he’d have lived there all winter, but he was driven down to the gorge by severe blizzards that could bury the forest roads in a layer of snow several yards deep. Then it was impossible to reach his clearing by horse or truck, and wading through the snowdrifts on foot was out of the question, so he’d come and live with his relatives in Birkiani, but as soon as the weather improved, he’d go back into the mountains.

I arrived at the herdsmen’s camp at noon. Late. Quiet and shaded, the clearing seemed deserted. I noticed the herdsmen’s shacks underneath the trees only once my eyes were used to the dirty, yellow foliage on the forest floor.

Toward evening, people started flocking to the camp, chestnut gatherers laden with bulging sacks and herdsmen rounding up barrel-shaped cows for the night. Along with them some large sheepdogs appeared; Omar kept a whole pack of them here to protect the herds from wolves and bears

The women had lit the stoves and were busily making supper, urging the children to go drive the animals into a pen. The men came and sat outside Omar’s house on logs set around a stone hearth. The younger ones went into the forest to fetch wood for the campfire.

Finally Omar appeared too. He sat down outside his house among the men and chopped some meat to make kebabs. He cut it into small pieces and speared them onto skewers whittled from twigs. Once the herdsmen had lit the campfire, Omar waved acrid smoke aside, positioned the skewers above the flames, and kept watch over the meat. Once he thought the kebabs were ready, he shared them among the men sitting in the circle. He raked aside some embers and threw whole handfuls of chestnuts into them.

“They’re delicious when they’re well roasted. Everything’s good that does people good,” he said, staring into the fire, and the herdsmen gathered around him exchanged inquiring glances, trying to guess whether Omar was just amusing the guest or starting one of his stories.

They cocked an ear, because there were profound truths in the tales he told by the campfire, answers to some vital questions, or clues about life that might be useful. They saw Omar as a sort of hermit and sage, someone who because of his own mixed fortunes and experiences had come close to things that ordinary people don’t understand.

He was a man of few words. Sometimes he said nothing for days on end, but was far away, lost in thought. At those times, people said he must be remembering the road he’d traveled, from the world of the living to the dead and back again, and that he shouldn’t be disturbed, or he might get lost and fail to find his way home.

After being wounded during the winter battle for Grozny, he had spent three days lying among the corpses in Minutka. The bullets had injured his spine and deprived him of the ability to move. He had lost consciousness, and when he regained it, he couldn’t feel anything, not even pain. Nor could he cough out words or make any sound. He could hear everything around him, not clearly, but as if at a distance, muffled by a roaring noise. He hadn’t lost his sight, but he couldn’t move his head, so all he could see was what was in front of him.

They cocked an ear, because there were profound truths in the tales he told by the campfire, answers to some vital questions, or clues about life that might be useful.

He didn’t immediately realize he was lying in a pile of corpses. The whole time it was dark, ranging from twilight to complete blackness. He figured he was in an enclosed space, a cellar perhaps. He could hear people’s voices around him and the thunder of explosions and gunfire farther away. They brought something up and laid it next to him. At one point, he heard someone say that they couldn’t wait any longer, but must start burying the dead. “The earth is frozen solid,” someone else said. “We could light a fire to make it a bit softer. Or we could pull up the cellar floor with a crowbar and dig a pit there,” the first voice replied. That was when Omar realized they’d assumed he was dead and were about to bury him with the corpses. They’d lay him in a pit dug in the cellar, toss corpses on top of him, and bury him alive. He felt a chill pass through him. It surprised him, because if he couldn’t feel pain, where could that cold shiver have come from? Maybe it was the terror they say you feel just before death, when you know it’s on its way and nothing can stop it, but you’re not ready for it yet, you’d like to live a bit longer, you still have so many things to do. It occurred to him that he’d survive if he didn’t close his eyes. The only way he could escape death was by catching someone’s gaze and answering it with a stare. He was afraid he’d fall asleep and lose consciousness, then he’d be done for, there’d be no hope of rescue. To drive off his tiredness, he thought through every detail of his entire life, year after year.

Suddenly he was startled by a dazzling light. Just as abruptly as it had flashed on, it went out again. He despaired at the thought that he had fallen asleep and missed that one, crucial moment. But the light returned—it was shifting, now closer, now farther away, but it didn’t go out. He realized that there were several sources of light. It looked as if it were coming from flashlights. He could hear voices, but he focused all his attention on the light, as if by sheer willpower he could force it to turn its beam on him. It flashed past close to him, almost sliding across his face, then vanishing, but it came straight back again. Now Omar could sense it, he knew it was stopping on his face. Dazzled by the brightness, he squinted, but then opened his eyes as wide as he could. Blinded, he couldn’t see a thing, but he clearly heard someone say, “There’s someone moving over here! This one’s alive!”

They extracted him from the pile of corpses, carried him out of the city on a stretcher by night, and drove him to a hospital in Georgia. He knew he’d been rescued, and was going to survive. But he still couldn’t move or feel anything, and the doctor said he might remain paralyzed for the rest of his life.

At first, he didn’t believe it, but as each day passed without any improvement, he surrendered increasingly to doubt and stopped fighting. When he was on the point of giving up and was desperately praying for death, despite having previously escaped it, he regained the feeling in his right hand and started to move his fingers. The doctors gathered around him in amazement. “It’s a miracle,” they said, shaking their heads. “It’s proof of how strongly he wanted to live.”

And Omar recovered, regaining control of his body until, finally, the doctors agreed that he was back in the land of the living for good and didn’t need them anymore. They told him to take care of himself and eat properly, and discharged him from the hospital. They asked if he had anywhere to go in the city, and when he said no, they advised him to go to the Pankisi Gorge, to join his own people. And that was how he had ended up at Lara’s house.

He told himself that as soon as he gathered his strength, he’d join Gelayev’s insurgent army. But before Omar was well enough for a journey across the mountains, Gelayev had set off for Abkhazia, where he was ambushed. Then Gelayev had made his way over the mountains to Ingushetia, where once again he was defeated by the Russians. Badly wounded, for a few months he had disappeared underground. Less than a year later, news went around the auls and valleys that he was recruiting a new unit, with the aim of breaking through to Chechnya and Dagestan, to go on fighting from there. Omar was pleased, because it looked as if Gelayev was planning to fight just across the border; he clearly wanted to have a safe base in Pankisi’s Kist villages, a hideout for the winter. So Omar looked forward to the moment when the insurgents would come down to the gorge. He wanted to join them, and now he was ready.

But Gelayev didn’t return to the gorge. In the middle of winter, he battled across the mountains with a small unit and, following the expedition to Chechnya, came back into Dagestan. Apparently from there he was planning to cross to the Georgian side and come to Pankisi, but he was ambushed by Russian troops. The insurgents scattered, but had no chance of escaping the manhunt that followed. Gelayev was killed fighting alone in the mountains.

“Someone must have given him away. There’s always a traitor,” Omar said when the conversation by the campfire turned to the insurgent commanders with whom I was familiar as a journalist. We were discussing which of them was better than the others and in what way.

“How many of them were there? One better, braver than another,” Omar mused. “Maskhadov, Basayev, Geliskhanov, Raduyev, Israpilov, Umarov, Barayev . . . But for me, the best of all was Gelayev. Maskhadov had experience as a professional artilleryman, Basayev and Raduyev were unrivaled in daring, but the only one I trusted was Gelayev—I couldn’t have entrusted my life to anyone else. I didn’t want to be in anyone else’s service. You go under someone’s command, you kill and you’re prepared to be killed, you empty your mind, you know nothing. And then you find out it was all in vain, you’ve just been risking your neck in a game, for someone else’s advantage. There’s treachery and deceit at every turn . . . so many good men were killed . . . all for nothing.”

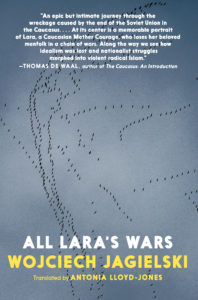

Wojciech Jagielski

Formerly a reporter at Gazeta Wyborcza, Poland’s first and biggest independent daily, Wojciech Jagielski has been witness to some of the most important political events of the end of the twentieth century. He is the recipient of several of Poland’s most prestigious awards for journalism, including a Bene Merito honorary decoration from the Polish government and the Dariusz Fikus award for excellence in journalism. Seen by many as the literary heir to Ryszard Kapuściński, he is the author of several books of in-depth reportage, including Towers of Stone: The Battle of Wills in Chechnya, which won Italy’s Letterature dal Fronte Award. Arguably Poland’s best-known contemporary non-fiction writer, Jagielski lives outside Warsaw.